34th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

Postwar booklet dedicated to the 34th Evacuation Hospital and its personnel covering the period July 15, 1942 > May 12, 1945, printed by Brückmann KG., Munich, Germany. Courtesy Mary O’Malley.

Introduction & Activation:

The 34th Evacuation Hospital was activated at Camp Barkeley, Abilene, Texas, 15 July 1942 (Armored Division Camp & Medical Replacement Training Center; acreage 69,879; troop capacity 3,192 Officers and 54,493 Enlisted Men –ed) under the command of Colonel Brooks C. Grant, MC. The cadre for the new unit was furnished by the 77th Evacuation Hospital (activated 10 May 1942 –ed) which arrived at Camp Barkeley on 4 August 1942, from Fort Leonard Wood, Rolla, Missouri (Engineer Replacement Training Center & Division Camp; acreage 72,168; troop capacity 2,352 Officers and 43,800 Enlisted Men –ed).

During the latter part of August and September 1942, 28 Medical Department Technicians were assigned to the new organization from Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colorado (designated General Hospital by War Department General Order # 40, dated 26 June 1920, 3417-bed capacity –ed). The remainder of the Enlisted personnel did not arrive until the last days of November.

The year 1943 began with 14 Officers and 265 Enlisted Men. In as much as fillers were not received until almost end of November 1942, the real work of training the EM took place during 1943.

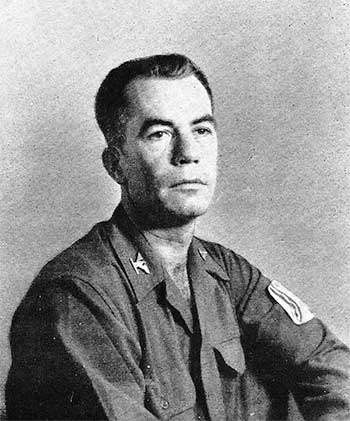

1945 Portrait of Colonel Kenneth A. Brewer, MC, Commanding. He took over command of the 34th Evacuation Hospital 10 February 1943, and was to serve as the unit’s CO throughout the remainder of the war.

Early in 1943, the 34th Evacuation Hospital underwent a change in organization. The unit was changed from a 750-bed installation (T/O 8-580 dated 2 July 1942) to a 400-bed hospital (T/O 8-581 dated 2 July 1942). This change made effective the following authorized strength:

| Evacuation Hospital (T/O 8-580) 47 Officers 0 Warrant Officers 52 Nurses 318 Enlisted Men |

Evacuation Hospital, Motorized (T/O 8-581) 39 Officers 1 Warrant Officer 48 Nurses 248 Enlisted Men |

This new Table of Organization made available organic transportation sufficient to move one-half of the functional hospital.

On 10 February 1943, Colonel Kenneth A. Brewer, MC arrived at Camp Barkeley, Abilene, Texas, to take over command of the new Hospital.

Training:

With the arrival of the new Commanding officer it was established that various omissions had been made in the Basic Training of Enlisted personnel. It was therefore considered necessary to do certain phases of Basic Training over again even though one group of EM was already engaged in advanced training. This was due to the fact that many of the fillers who had arrived came to the new organization directly from Induction Centers and had not undergone any Basic Training at a Medical Replacement Training Center.

After a period of strenuous and intensive Basic Training the prescribed tests were taken and a grade of “very satisfactory” was earned. Unit training was then commenced. During this time, many of the men were sent to various Medical Department Technical Schools.

The 34th Evac received its orders to proceed to the Louisiana Maneuvers from Camp Barkeley, Texas, leaving on 9 June 1943 and arriving at the designated bivouac area in the vicinity of Jasper, Texas, 11 June 1943. The highlight of this trip was an all-night bivouac at Lufkin, Texas, where the civilian population went all out to show them a good time. Movement took place by motor convoy while unit equipment was shipped by rail.

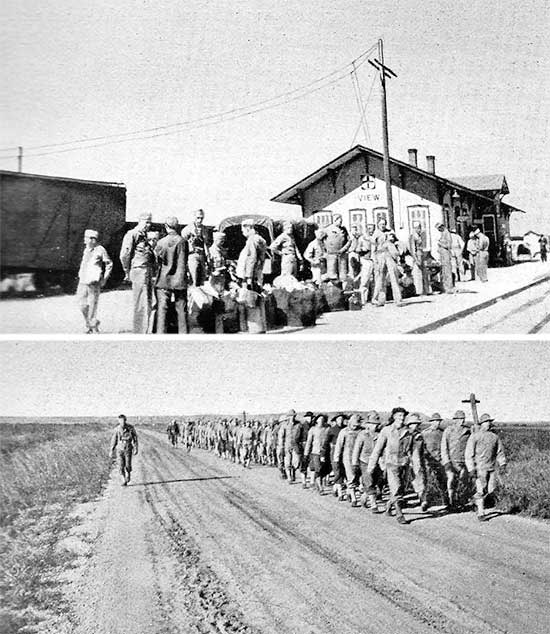

Top: Medical / Surgical Technicians of the 34th Evacuation Hospital at the View railway station, Texas, on their way to more specialized training at Fitzsimons General Hospital, Denver, Colorado. Bottom: Personnel of the 34th Evacuation Hospital on a road march, somewhere in Texas.

The first group of ANC Officers assigned to the Hospital joined Jasper, Texas, for the maneuver period. During the time on maneuvers, eight different moves were accomplished. All were effected by motor convoy and in accordance with the tactical situation.

Patients admitted to the 34th Evac during the 17-week period of operation numbered 4,051. Approximately 1/3 of this number were transferred to a Station Hospital for further treatment. The balance were returned to duty.

Recreational activities for the staff and personnel were varied and many while on maneuvers. Trips to nearby cities such as Shreveport, Leesville, Alexandria, or Natchitoches, were arranged during every break. Fifteen (15%) percent of the command received furloughs from the maneuver area and many took the opportunity to visit New Orleans on three-day passes. The Hospital PX was well stocked with coca-cola and other tasty tidbits excluded from the regular Army rations.

The Louisiana Maneuvers provided the Hospital with an excellent realistic period of training. The Enlisted personnel, in particular benefited as the practical field experience gained supplemented the many courses of instruction taken during overall training.

The 34th Evacuation Hospital received a general rating of “excellent” for these Maneuvers which ended with the unit’s return to Camp Barkeley, Texas, on 5 October 1943.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

The remainder of the year was spent in preparing for movement overseas. Final training tests were taken at this time and all personnel were passed with high ratings.

Additional furloughs were granted and on 7 January 1944 the organization departed from Camp Barkeley, Texas by rail for an “unknown” destination. This unknown destination proved to be Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for New York Port of Embarkation; acreage 1,815; troop capacity 2,074 Officers and 35,386 Enlisted Men –ed). After a three-day and night trip which took the 34th Evac across the entire width of the continent, from Texas into Canada, they reached the east coast Camp. Upon arrival, the entire unit were housed in two-story barracks, and subsequently issued all additional clothing and other equipment that was deemed necessary for troops going to serve overseas.

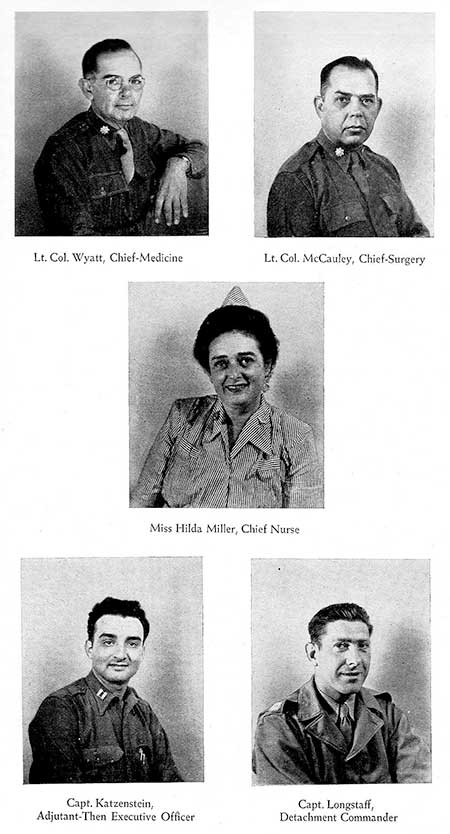

Vintage photograph illustrating some of the Staff of the 34th Evacuation Hospital. Lt. Colonel Arthur T. Wyatt; Lt. Colonel Ernest W. McCauley; Captain Hilda Miller; Captain Seymour Katzenstein; and Captain Ralph S. Longstaff, Jr.

The proximity of Camp Kilmer to New York City was very appropriate and each of the men took advantage to see the world’s largest city. Time at this station was spent in attending training films showing procedures for overseas movement, lectures, drill and mass athletics, including the last formalities and immunization shots. Post Exchange Number 3 at the Staging Area would not be forgotten by the personnel who transited through the area, and nor would the barbers whose abilities in hair cutting or trimming were merely confined to the GI variety.

Finally after a 31-day stay at Camp Kilmer, New Jersey, during which period, several “alert” orders were received, the organization entrucked for the docks of New York, where they were to board ship for the Atlantic crossing.

Atlantic Crossing:

After arrival at the appropriate pier and a last roster call, the organization boarded the British Hospital Ship HMHS “El Nil” (initially built in 1916 for Deutsche Ost-Afrika Linie, christened Marie Woermann, handed over to Great Britain in 1921, sold to Rotterdamsche Lloyd for service in Java, sold to Misr Navigation Company Egypt in 1933, and finally taken over by the British, sent to the US for conversion into a Hospital Ship in 1943 –ed).

The movement was accomplished on two days; 11 + 12 February 1944. Only about half of the organization boarded the ship the first day, while the remainder went aboard the following day. Carrying the 34th Evac was the vessel’s first mission prior to delivery to His Majesty’s Government.

On 12 February, she pulled away from the docks and started into the Hudson River, and by late afternoon HMHS “El Nil” sailed by the Statue of Liberty and out into the open sea.

The trip was a hectic one, as the vessel was beset with numerous mechanical difficulties. The first stop was Halifax, Nova Scotia, where damage to the ship during the first lapse of the voyage was repaired. No passengers were allowed to go ashore. After leaving Halifax, the seas became very rough and the voyage continued under adverse weather conditions. High waves pounded over the decks tearing loose a couple of lifeboats and carrying them off to sea; high winds cracked the vessel’s superstructure and a leak developed in the boiler room. For a while the pumps failed to work and men had to bail out water. It was quite dangerous, although the majority of the ship’s passengers were not aware of the seriousness of the situation.

Recreation during the crossing was confined to card playing and some reading, and being just plain seasick! Food on board was terrible, and after having been introduced to English eating habits the men almost became sick from the odor of frying herrings emanating from the galleys every morning.

Vintage photograph illustrating His Majesty’s Hospital Ship “El Nil”, No. 53, which carried the 34th Evacuation Hospital across the Atlantic, departing New York POE 12 February 1944.

It was a pleasant feeling to see the end of a long voyage across the Atlantic. The last part of the ship’s journey took the “El Nil” around the tip of Northern Ireland, down through the Irish Sea, past the Isle of Man, and into the port of Liverpool, England.

United Kingdom:

The 34th Evacuation Hospital reached Liverpool on 27 February 1944. After the usual procedure of “hurry up and wait”, the personnel debarked and were transported to the railroad station in US Army trucks. The troop train took the organization to Altrincham, Cheshire County, after a welcome cup of coffee and donuts furnished by the local American Red Cross committee at the Liverpool train station. Immediately upon leaving the train at Altrincham the men were formally introduced to the famous expression of “any gum, chum?”. It was already dark when the group arrived at their billets, and some confusion took place as the men were divided up to occupy the separate living quarters. They would soon all become acquainted with the life of a modest, suburban, English village. Training and preparation for operations on the continent were completed in the United Kingdom. One of the lessons learned was that an Evacuation Hospital could not function if scattered all over the countryside as had been practiced on Maneuvers in the Zone of Interior. It was the SOP developed in England that was later used and applied on the continent in the establishment of the Hospital Plant. Other activities consisted of viewing training films, study chemical warfare charts, enemy and friendly aircraft models and charts, orientation maps, etc. Physical conditioning in the form of hikes, drill, and mass athletics was also included in this training program.

Men attended courses at the Aircraft Recognition School at Ringway airport. Enlisted Technicians received special lectures in x-ray apparatus repair and maintenance, care of psychiatric patients, signal switchboard operations, bomb disposal, and vehicle waterproofing. Medical Officers attended the Medical Field Service School at Shrivenham, Wiltshire (the American School Center established by ETOUSA in the summer of 1942 was set up to train Officer Candidates and various categories of Specialists –ed), and several Physicians were placed on DS with US Army General and Station Hospitals and English Civilian Hospitals to practice their specialties. Army Nurse Corps Officers received special courses in psychiatry and anesthesia.

During the unit’s stay in Cheshire County, a large diversity of activities were available for the members of the organization. The men and women started learning English habits, and tasted “mild and bitters”, “chips and fish”, visited typical pubs and inns, and built social activities in the neighborhood. Extra activities when off duty included bicycle riding, golf, dancing, sightseeing, and trips to large cities such as Manchester and London, as well as motion pictures and theater plays.

During the week of 7 April 1944, Cheshire County observed the “Salute the Soldier Week”. Numerous parades were staged with American military participating. The 34th Evac participated in one such parade held at nearby Bowden and Hale. All in all, the Hospital unit were very fortunate to be in such a place as Altrincham, where the community opened its arms to the Yanks …

Personnel of the 34th Evacuation Hospital parading during the “Salute the Soldier Week” in Cheshire County, England.

The war and the mission for which the men and women of the 34th had trained for became more of a reality on 15 June 1944, at which time the organization departed from Altrincham for another “unknown” destination. It proved to be the Marshalling Area at Tidworth, England, where the entire group remained until 20 June. During their stay equipment and vehicles were thoroughly prepared for movement over water. From the marshalling area the next move was to the Staging Area in the vicinity of Southampton, which brought it nearer to its destination. It wouldn’t be long now before the next move which would include crossing the English Channel. Once safely inside the Staging Area, the men received US$ 4.00 in French Currency (the so-called “Invasion” money or Supplemental French Franc Currency -ed), extra cigarette rations, food, and several other items for which there was a need during the first days in Normandy. The first trip to the docks for boarding turned out to be a dry run and upon the unit’s return to the Staging Area rumors ran rampant as to the reason. The staff finally learned that it was because of rough channel water that the crossing had been delayed.

France:

Finally on 22 June 1944 the Hospital group boarded HMS “Empire Broadsword” (LCI built in the UK and launched in August 1943, served in the ETO with British forces, and sunk by a mine on 2 July 1944 –ed) and had their first taste of a troopship. The first night was spent at anchor just outside the port and the following day the crossing took place in convoy. The 34th Evacuation Hospital landed on Utah Beach on 23 June 1944.

Following the crossing, the first night on continental France was spent at “Transit Area B” in foxholes, as many of these had been left by front line troops. Some men who didn’t have any, started digging their own, as the organization had been warned that German planes strafed these areas every night. The night however was spent quietly. Unfortunately the organic vehicles were delayed in the Channel crossing and did not make their appearance until 2 July. While waiting for the equipment, the 34th was divided into two separate groups and farmed out to the 96th and 97th Evacuation Hospitals, respectively at Sainte-Mère-Eglise and Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte. The experience gained by working with and treating battle casualties at these hospitals was very helpful and much of it was put to good use when the unit eventually opened their own hospital. By the time the equipment arrived, the personnel had a much better idea as to just what was going to be expected of them.

A couple of days were spent while bivouacking, in de-waterproofing the vehicles and equipment as well as painting large Geneva Convention red crosses on the tentage. All other equipment was checked and on 4 July 1944, the organization entrucked for its first installation site, where they arrived the same day and started pitching the large hospital tents. On 5 July 1944, at 0600 hours, the 34th Evacuation Hospital opened in a field overlooking the city of Carentan, France, under control of First United States Army (code name “Master” –ed).

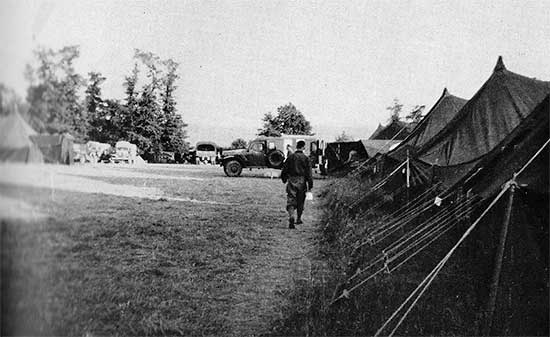

Partial view of the 34th Evacuation Hospital’s set up near Carentan, France. Ambulance unloading casualties at the Receiving. Photo taken some time between 5 July and 6 August 1944.

6 July 1944 was to become an important day for the organization. On instructions of FUSA Headquarters an inspection tour was organized with the aim to visit a number of Hospitals operating in Normandy. Brigadier General John A. Rogers, Third United States Army Surgeon, accompanied by Major General Albert W. Kenner, SHAEF Surgeon, first stopped at the 83d Infantry Division CP and subsequently visited the 34th as well as other Evacuation Hospitals operating on the continent.

During the initial phase and following operations of “Operation Overlord” Evacuation Hospitals functioned throughout the entire operations with little relief. The number of Evacuation and Field Hospitals set up for the First United States Army during the planning phase was for a field Army composed of three Corps. With the build-up of the First US Army on the continent, first by VIII Corps and later by Third United States Army units, the FUSA medical service was supplemented during the period 26 June 1944 to 1 August 1944, by the following medical organizations of General G. S. Patton’s Third US Army (code name “Lucky” –ed):

16th Field Hospital

32d Evacuation Hospital

34th Evacuation Hospital

35th Evacuation Hospital

39th Evacuation Hospital

100th Evacuation Hospital

102d Evacuation Hospital

103d Evacuation Hospital

104th Evacuation Hospital

106th Evacuation Hospital

107th Evacuation Hospital

109th Evacuation Hospital

All of these units reverted to the TUSA control on 1 August with the exception of the 106th and 109th Evacuation Hospitals, which were returned at a later date. Advance Section, Communications Zone (ADSEC) made the 77th Evacuation Hospital available for use by the First US Army on 21 July 1944, along with three Ambulance Companies which were given the task of transferring patients from the Evacuation Hospitals to the beaches. Throughout this period Evacuation Hospitals were utilized by closing a Hospital and leapfrogging it forward to a new location. Hospitals were established as far forward as the tactical situation would permit, usually in front of Army Corps rear boundaries. At the height of operations for the period 6 June 1944 to 31 July 1944, there were 22 Evacuation and 6 Field Hospitals assigned and attached to FUSA for medically supporting 16 active combat Divisions.

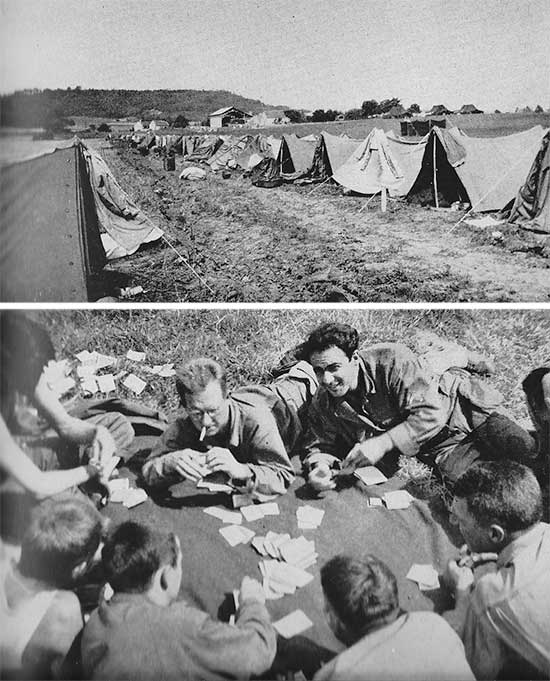

Photographs illustrating the Enlisted Men’s bivouac at Fougères, France. Photo taken in the period 7 > 15 August 1944.

Overview of admissions received at the 34th Evacuation Hospital during the month of July 1944:

- week ending 7 July 1944 > 574 Admissions

- week ending 14 July 1944 > 795 Admissions

- week ending 21 July 1944 > 634 Admissions

- week ending 28 July 1944 > 543 Admissions

The organization’s “baptism under fire” at Carentan, Normandy, was probably the most harrowing of all experiences. None of the training, including the Louisiana Maneuvers, had totally prepared the 34th for what was to come and what did come! By 2030 hours, 5 July 1944, 525 patients had been received. All personnel were operating on a fulltime basis. The Hospital was situated 2.9 miles from Carentan and at the beginning only three and one-half miles from the front. This placed the installation and personnel in constant danger of any counter-battery fire but luckily the period passed without any damage or injury. The Hospital was still located at Carentan when the battle for Saint-Lô was raging and many casualties were from that sector. The men witnessed the drone of a thousand aircraft overhead when the Army Air Forces blasted a hole through the lines in the area around and in Saint-Lô through which Patton’s Third US Army poured as it started its drive across France. In line with the above, the 34th Evacuation Hospital reverted back to TUSA.

The Hospital’s statistical records bear out the fact that Carentan, France, was the landmark that stood out from all other locations over the long trek across the European Continent. It was here that 34th Evac encountered the highest census of serious battle casualties and it was also in this area that the greatest number of deaths occurred. This was due to the fact that patients’ conditions were so critical and their injuries so extensive that death took place in spite of what surgical skills could do.

Stations in France – 34th Evacuation Hospital

Carentan – 5 July 1944 > 6 August 1944

Fougères – 7 August 1944 > 15 August 1944

Digny, Etampes, Tauxières-Mutry – 17 August 1944 > 7 September 1944

Verdun – 8 September 1944 > 29 November 1944

Metz – 30 November 1944 > 1 February 1945

The first and only night move made took place from Carentan to Fougères with the first serial of the motor convoy leaving Carentan at 0100, 7 August 1944. The first group arrived at the new area 2/3 miles southeast of Fougères at 1100 the same day. By 2000 hours, the same evening, the Hospital was opened and started receiving patients. The Fougères area would be remembered for its dusty highway that was located near the Hospital and the large crowds of curious French locals who came to view the field installation. It was here that Enlisted Men started out shopping for extra food, such as fresh eggs.

The only immediate threat to the outfit came in this area when the enemy launched a counter-attack in the vicinity of Avranches, near Mortain, trying to separate a portion of TUSA elements from the remainder of Allied forces. This would have severed the main supply artery, and cut off the 34th Evac if the attack would have been successful! After a nine-day stay in this area, the organization packed for a movement to a different location keeping close on the heels of the now rapidly advancing Third US Army armored columns, which had started the drive for Paris, the French capital.

Main entrance of the 34th Evacuation Hospital, while established in a French Military Hospital at Verdun, France. Photo taken some time in September 1944.

Enemy PWs were utilized throughout most of the period at the Evacuation Hospitals (also other Hospitals used their services –ed). This policy was closely coordinated with the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-1 and the Provost Marshal, Headquarters FUSA. This became necessary due to the fact that T/O of Evac Hospitals was such that during periods when large numbers of casualties were being admitted, the Enlisted personnel were needed for the most urgent work of caring for the sick and wounded. It was therefore necessary that additional manpower be made available for general work details, such as litter bearing, latrine digging, garbage collecting and pit digging, and other non-medical labor. Usually around 40 prisoners of war (non-medical personnel) were attached to each Evacuation Hospital.

During the period beginning mid-August 1944, the organization stayed a comparatively short period of time in the next three hospital sites because of the speed with which the Army was advancing.

An area one-half mile south of Digny became the next location. Here, the greatest number of enemy patients were admitted. It was also in this area that the 34th Evac made the acquaintenance for the first time of a unified French force. They consisted of an Armored Division completely equipped with American-made materiel. This Division was among the troops that would liberate Paris, France in August (Deuxième Division Blindée –ed).

The next area near Etampes, only five miles away to be exact, better remembered as the Bouville area, was the unit’s next stop and bivouac. It was reached on 24 August 1944. In this particular site, Army Engineers constructed roadways through alfalfa fields to the Hospital site. They worked on them for 3 full days, and two days after they had finished, the 34th received orders to move once more.

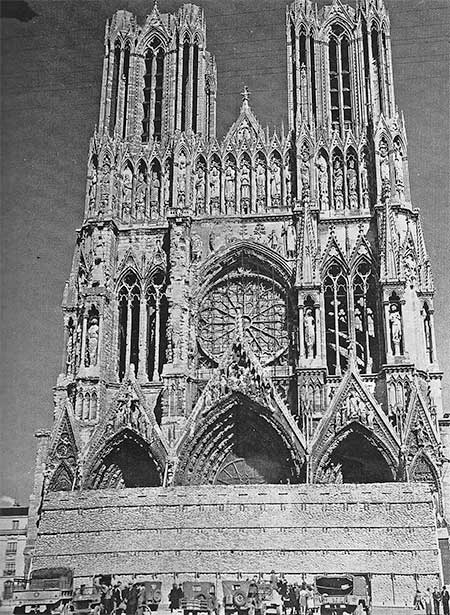

The next move went by motor convoy to Tauxières-Mutry, some 18 miles south of the city of Reims. The Hospital was set up on the grounds of an estate, and as it was not far away from Reims, this enabled the staff and personnel to visit that city and especially the world-famous Reims Cathedral. It was in this area that more than a few members of the organization became acquainted with the highly-advertised French Champagne. During the Hospital’s stay in Reims, American armor fanned out beyond Reims and Verdun (of WWI fame –ed) fell.

Side view of the 34th Evacuation Hospital at Metz, France. The organization took over buildings formerly occupied by the Wehrmacht and used as a military hospital during their occupation of France. Photograph taken in the winter of 1944-45.

The next move, which brought the unit to Verdun was significant, as this was the first time the Hospital would occupy buildings. The men set up in a military Hospital that had been taken over by the Germans. There was much abandoned equipment which impressed the command by both its quality and quantity.

An advance party, including a clean-up squad left Tauxières two days before the Hospital moved in order to clean and ready the buildings for occupancy. They did a wonderful job and when the main body arrived everything was in readiness for installation of the plant. The task remained somewhat difficult mainly because of the differences in the unit’s electrical outlay and the one installed in the premises. It became necessary to arrange the different sections in the buildings to provide for a free and organized movement of patients that had already become routine in the field. This did require considerable juggling, but when finally accomplished, presented an efficient and workable military hospital.

During their stay in Verdun, the 34th received the visit of the Third US Army Band on 15 September 1944 (official designation: 61st Army Ground Forces Band, under the direction of CWO Gregorio A. Diaz –ed) which was on a tour for 4 days playing on request of TUSA’s CG for the 12th Evacuation Hospital (north of Vadelaincourt); 34th Evacuation Hospital (Verdun); 104th Evacuation Hospital (northeast of Amnéville); and the 109th Evacuation Hospital (Doncourt-lès Conflans).

Verdun proved another landmark for the 34th Evac. The number of patients admitted at one time doubled the unit’s capacity which was provided by the T/O. A large number of cases were afflicted with trenchfoot due to the winter’s obstinacy in keeping the terrain damp and muddy and the rivers swollen. Enlisted Men quartered in the Hospital’s basement were forced to double up with men living in other portions of the buildings in order to make room for the overflow of incoming patients. The Moselle River, flowing directly behind the Hospital, was at flood stage and decided to pay the 34th Evacuation a visit. As a result, the basements were flooded and mass evacuation from these quarters became necessary. Meanwhile aided by a massive use of artillery, TUSA pushed across the Meurthe River and established bridgeheads across the Moselle River, with progress slow and costly. Terrific battles were fought along the Moselle as Third United States Army battled to breach the outer defenses of the city of Metz, including the famous Fort Driant (which would only surrender 8 December 1944 –ed). Unfortunately the enemy had succeeded in stabilizing his front and Third US Army was ordered to hold its position until an adequate supply build-up would permit a resumption of the offensive, because of a severe shortage of ammunition as well a gasoline.

Scene illustrating evacuation of casualties along the Moselle Front, France. Photo taken during fall / winter of 1944.

The organization’s FIRST Thanksgiving in the European Theater was observed at Verdun with the usual splendor and turkey with all the trimmings. Passes and other opportunities allowed the command to visit the city of Verdun and the surrounding countryside. Verdun was moreover especially significant because of its relation to the Great War!

On 8 November 1944, General George S. Patton resumed the offensive, capturing Metz and opening the Saar Campaign and finally dashing the enemy’s hopes for a winter stalemate. After enemy resistance inside the Fortress of Metz ended on 22 November 1944, the unit sent a reconnaissance party into town the next day to examine the German military hospital there and report whether it would be suitable for utilization. As it was found to suit the organization’s purposes it was decided to occupy the buildings. Movement to the site was however delayed until certain Divisional medical units vacated the buildings.

Meanwhile the strong forts outside the city remaining in enemy hands inhibited normal movement to the Hospital which on 27 – 28 and 29 November 1944 was accompanied by sporadic artillery and other gunfire from these formidable redoubts. The full fury of the winter caught everyone in Metz and that particular location would be remembered for the zero weather and the lack of proper heating accommodations. Other specific memories of Metz were the outdoor latrines, the lack of running water, the faulty lighting, and the endless verbal battles with French maintenance crews. Metz had felt the might of Allied airpower and artillery and had suffered considerably.

General view illustrating some aspects of the severe weather conditions encountered during the Alsace-Lorraine Campaign, France.

The patient census was second to Verdun in the individual area admittance totals. The number of battle casualties however was relatively not that great and a sizeable proportion of patients went to the Medical Service. During the “Battle of the Bulge”, the 34th Evacuation Hospital received many battle casualties especially after the German ring around the city of Bastogne, Belgium, had been broken.

Metz became the site of the unit’s FIRST Christmas and New Year in Europe.

Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg:

On 2 February 1945, the 34th Evac moved to Luxembourg in support of Third US Amy troops engaged in preparatory attacks for the drive to the Rhine River. Opposition in the sector was very strong and the longest ever sustained period of continuous surgery was encountered during this period. For practically the entire stay there was no let up in the continuous flow of operation in all sections of the Hospital.

The plant was located in a Convent previously used as a military hospital by the enemy. The building was very convenient for this purpose and housed all sections. However, because of the height, daily difficulties occurred with the litter bearers who had to carry patients from the receiving to surgery and from surgery to the different wards. Officers and Nurses were quartered in separate buildings across the street, while Enlisted Men were billeted in dormitories formerly used by theological students. The latter quarters were approximately one-half mile from the Hospital.

The serenity of daily hospital routine was disrupted on the night of 15 March 1945 when German long-range artillery fired from the vicinity of Trier landed near the 34th Evac and also close to the EM’s quarters. The objective of these shells was a huge stone bridge spanning the valley which was situated on the main supply road to the front. Fortunately, the shelling was not very accurate and the only damage was broken glass (many windows were shattered) and a gaping hole in the street. The incident reminded many personnel of the early days spent at Carentan, France.

Vintage photograph illustrating the 34th Evacuation Hospital’s installations (Convent) in Luxembourg, Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, where the organization was established from 2 February to 30 March 1945.

Stations in Luxembourg – 34th Evacuation Hospital

Luxembourg – 2 February 1945 > 30 March 1945

Germany:

On 24 March 1945, Frankfurt-am-Main fell to General Patton’s forces and the Hospital’s next location was assured.

The organization was to leave in two different convoys. The first echelon left Luxembourg on 30 March and entered Germany, enemy country, the same day. This group stopped overnight at Bad Kreuznach in Allied Military Government (AMGOT –ed) buildings then continued on to Frankfurt the next day. The second echelon made the trip without any stopovers. The move into Germany proved special. As the 34th crossed the Luxembourg-German border, they were greeted by huge signs telling them that they were “entering Germany, an enemy country, and not to fraternize”. This word was to become as much part of the daily vocabulary as “chow”.

The men witnessed the sad situation and for the first time viewed the wreckage caused by Allied bombing and shelling. Symbolic was the sight of the many white flags flying from windows, balconies, and doorways. There were no longer crowds of cheering and enthusiastic people lining the streets as the convoys passed through “liberated” towns. What the command saw was sullenness and bafflement, all signs of a conquered people who seemingly could not realize how it all had happened.

Crossing the Rhine River on a pontoon bridge and under a heavy smoke screen was an experience that nobody would forget soon. Upon arrival the Hospital was installed in a number of buildings that had previously housed the famous University of Frankfurt-am-Main Medical School (Universitäts Kliniken und Polikliniken –ed). Many German patients were still in the buildings as there had been no time to evacuate them. They were eventually moved to the buildings in the hospital area staffed by enemy GC-protected medical personnel.

The 34th Evac opened and started receiving patients as of 0001 hours, 3 April 1945. During the succeeding days, work continued making things more convenient for operation of the hospital plant. It was here that it was decided to hire a large number of German civilians to help around the messes. Several German Nurses were also placed on partial duty in the Hospital.

For the first time in the organization’s history, many of the patients received were recently liberated Allied Prisoners of War (RAMPs –ed). Happy boys they were!

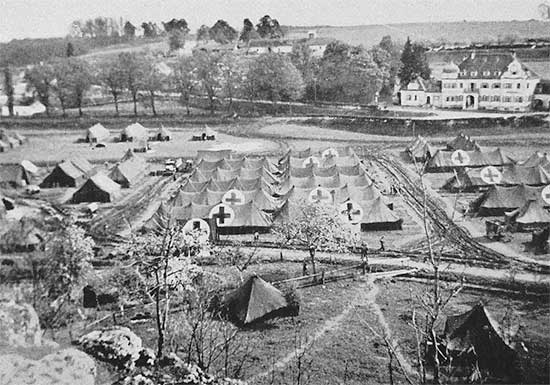

General view of the 34th Evacuation Hospital during its set up in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany. This was the unit’s first stay on enemy soil. The Hospital remained in Frankfurt from 30 March to 13 April 1945.

Stations in Germany – 34th Evacuation Hospital

Frankfurt-am-Main – 30 March 1945 > 13 April 1945

Suhl – 14 April 1945 > 29 April 1945

Sandersdorf – 28 April 1945 > 12 May 1945

When leaving the city of Frankfurt-am-Main the men were able to see the scenes of total destruction caused by Allied Air Forces on the larger enemy cities.

The first echelon left Frankfurt by motor convoy 13 April 1945 and proceeded to a new site near Suhl. The remaining echelon followed the next day. It must be said that much of the country between the two cities had only recently been conquered and smoking ruins were still visible.

The building designated for the 34th had formerly been used as a Luftwaffe Cadet Training Center. It was located on top of one of the many hills in the area and this was a welcome relief from previous experience with housing. The countryside was simply beautiful and this certainly proved one of the most attractive locations the unit had ever known.

Overall hospital admittance in this area fell off considerably and this fact was very much appreciated by all members of the command. All signs meanwhile seemed to point to an early termination of the war and every man was doing his job with the expectancy of seeing it all ended in a short time…

Partial aerial view of the 34th Evacuation Hospital installations (under tentage) at Sandersdorf, Germany. This was to become the unit’s last setup until the end of the war and the organization’s last stay in the European Theater. The unit remained at Sandersdorf from 28 April to 12 May 1945, where it celebrated V-E Day as well as Memorial Day services.

Saturday afternoon, this was 28 April 1945, the first shuttle of organic trucks carrying OR section personnel and equipment arrived at a new installation site near Sandersdorf, partly occupied by a half dozen light field artillery observation planes. Working with speed the Hospital was set up quickly and after pitching the tents the installation was ready for operation by 1800, the following evening; which meant six hours ahead of the scheduled hour set for receiving patients.

During the recent moves it was apparent from the looks of the country that the men were moving hastily against disorganized and retreating Germans. It was gradually realized after the organization started receiving more German wounded than American patients. The ensuing days brought news via the radio and The Stars and Stripes newspapers that Adolf Hitler was dead and German resistance was crumbling on all fronts. The Soviets had almost captured Berlin. On 4 May 1945 the command was informed that hostilities had ceased along the front they were serving. A few days later on 8 May 1945 SHAEF announced that the war had ended, and officially proclaimed V-E Day!

It must be stated that this announcement brought little response from the unit as a whole. Chaplain Albert O. Mattheis held his Wednesday evening service as usual, and all personnel reported to their respective sections for duty to care for a dwindling number of US patients. During the next few days most of the wounded were evacuated and duties confined to caring for a few medical cases from nearby-stationed units.

To anyone walking through the hospital area on the evening of 12 May 1945 it was very obvious that blackout regulations had been lifted. The gleam of lights from the open tents, and the glow of bonfires from the pup tents was a more than welcome sight to all who had been living under strict blackout conditions for the past fifteen months. During the remaining days spent in the Sandersdorf area, staff and personnel of the command found time to participate in the extensive athletics program that was started, including sports like volley ball – base ball – horse shoes – running – swimming, and the now familiar “going fishing”.

Vintage photograph of the famous Reims Cathedral, France. Part of a major tourist attraction, the place was visited by numerous soldiers during passes at the end of the war.

A massive turnover of Enlisted personnel took place at the 12th Evacuation Hospital and by mid-July 1945 a large number of high-point men were sent to the 34th Evacuation and the 104th Evacuation Hospitals in exchange for low-point men from these units. It then took days to sort out the skills and experience of the new personnel before they could be assigned to the appropriate duties.

Summary:

The 34th Evacuation Hospital took an active part in the war against Germany from 5 July 1994 to 8 May 1945. Overall admissions numbered 24,477 patients. The average daily admittance was 90 patients. The mortality rate of American casualties, not including patients, dead on arrival, was 1.42%. Outpatients treated during the last 10 months of operation totaled 20,230. Of these, 11,000 were treated in the dispensary, 3,380 needed dental care, and 5,850 were treated in the EENT clinic.

The Surgical Service performed 13,369 procedures and administered 11,047 anesthetics. The monetary value of drugs, chemicals, and biological consumed totaled US$ 216,473. This great total included approximately US$ 149,000 for the new drug, penicillin.

Gasoline consumption in 1944 averaged 7,000 gallons per month, compared with better than 14,000 in 1945!

Some Medical Statistics – Third United States Army

Patients transferred by Third US Army ambulances from Infantry / Armored Division Clearing Stations to Army Hospitals during 1 August 1944 to 8 May 1945, numbered 269,187. Evacuated from the Army sector were 164,810 patients; 28,826 by air, 91,005 by road,1,164 by ship, and 43,815 by rail. Mortality from all types of battle casualties treated in TUSA Hospitals amounted to 2.78%. The percentage of deaths from all causes to dispositions made of all cases was 1.4%. Third US Army patients returned to duty without evacuation from the Army area numbered 114,024, or 43.5%, as compared to dispositions.

Senior Staff – 34th Evacuation Hospital

Colonel Kenneth A. Brewer > Commanding Officer

Captain Seymour Katzenstein > Executive Officer

Lt. Colonel Arthur T. Wyatt > Chief Medical Service

Lt. Colonel Edward W. McCalley > Chief Surgical Service

First Lieutenant Hilda Miller > Chief Nurse

First Lieutenant Albert O. Mattheis > Chaplain

Captain Ralph S. Longstaff, Jr. > Detachment Commander

Operations Map illustrating the route taken by the 34th Evacuation Hospital while serving in the European Theater of Operations.

Official Campaign Credits – 34th Evacuation Hospital

Normandy

Northern France

Rhineland

Central Europe

Meritorious Service Unit Plaque – 34th Evacuation Hospital

The 34th Evacuation Hospital was awarded the Meritorious Service Unit Plaque for the months of November and December 1944 and January and February 1945. The award was given “for superior performance of duty and outstanding devotion to duty in the performance of exceptionally difficult tasks, achievements, and maintenance of a high standard of discipline”.

(the Meritorious Service Unit Plaque was established by War Department Circular No. 345, dated 23 August 1944. The circular provided that military personnel assigned or attached to a service organization were entitled to wear the Meritorious Service Unit Insignia on the outside half of the right sleeve of the service coat and shirt, four inches above the end of the sleeve. The award was limited to service units for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services for at least six continuous months during a period of military operations against an armed enemy and restricted to services performed between January 1, 1944 and September 15, 1946 –ed).

Personnel Roster:

Photograph illustrating Headquarters Staff of the 34th Evacuation Hospital. From L to R: First Lieutenant Daniel B. Kohn; Enlisted Men Lawrence Bruemmer; Robert A. Fletcher; and Captain Seymour Katzenstein.

| Officers | |

| Kenneth A. Brewer, Colonel | E. W. McCauley, Lt. Colonel |

| Edward F. Bruning, Captain | Frank V. Mondrik, Captain |

| Thomas J. Costigan, Major | Paul L. Neiswander, Captain |

| Efrem Feld, 1st Lieutenant | Hardgrove S. Norris, Captain |

| Martin Feldstein, Captain | Spencer A. O’Brien |

| Harry Q. Gahagan, Captain | Ross Owens, Captain |

| Robert Glendening, Captain | Anthony J. Pacioni |

| Marion L. Gordon, Captain | Nicholas Polites, Major |

| Edward B. Grossman, Captain | Byron G. Rutledge, Captain |

| Vonnie A. Hall, Captain | Raymond N. Shapiro, Major |

| Gurney E. Hetrick, Captain | Nathan Silver, Captain |

| Robert C. Jackson | Wallace T. Smith, Captain |

| Seymour Katzenstein, Captain | Melvin J. Stufflebeam, Captain |

| Elmer A. Kleefield | Joseph V. Tobacco, Captain |

| Daniel B. Kohn, 1st Lieutenant | Verne W. Swigert |

| James P. Laughrey | Jacob M. Werle, Captain |

| John R. Law, Major | Nathan Wolf, Major |

| Ralph S. Longstaff, Jr., Captain | Alfred Wolfarth, Captain |

| Albert O. Mattheis | Arthur T. Wyatt, Lt. Colonel |

| Webster B. Majors, Major |

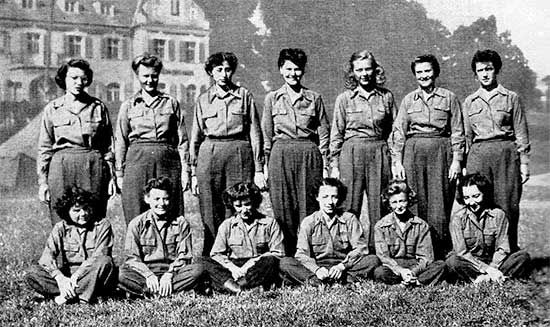

Photograph illustrating some ANC Officers of the 34th Evacuation Hospital Surgical Section. Back Row, from L to R: Lieutenants Harriet G. Markle; Harriet J. Ives; Rose E. Grinberg; Pauline E. Kruzik; Delphine J. Pasinski; Ethel M. Peters; Esther R. McCarthy. Front Row, from L to R: Iris J. Ezzell; Sally T. Watson; Nedra E. Schwartz; Helen A. Surface; Marjorie Chalkley; Laird Sullivan.

| Nurses | |

| Margaret Aldrich | Pauline E. Kruzik |

| Marion C. Arner (1st Lieutenant) | Florine P. Mangleberger |

| Helen Bailey | Harriet G. Markle |

| Eva L. Brachert | Esther R. McCarthy |

| Doris J. Caulk (1st Lieutenant, N-772153) | Helen C. McDonald |

| Marjorie Chalkley | Hilda Miller |

| Lois E. Dean | Delphine J. Pasinski |

| Mary Duff | Ruth L. Penoyar |

| Ruby G. Ellisor | Ethel M. Peters |

| Mary F. Elwell | Nedra E. Schwarz |

| Iris J. Ezzell | Berneda A. Serfass |

| Betty L. Fleming | Laird Sullivan |

| Frances M. Fuller | Helen A. Surface |

| Dorothy Galblum | Patricia L. Trainor |

| Sara Anne Gallagher | Nellie E. Walls |

| Helen M. Germain | Ruth E. Watson |

| Vida B. Gregorka | Sally T. Watson |

| Rose E. Grinberg | Eva L. Wiant |

| Harriet J. Ives | Marguerite A. Yerger |

| Nancy M. Kiess (1st Lieutenant) |

Photograph illustrating Enlisted Men of the 34th Evacuation Hospital Operating Section. Third Row, from L to R: John H. Hirtle; Willis E. Delker; George Lansdale; Harley M. Johnson; John G. Coffland. Second Row, from L to R: Mirko Magulac; Eugene R. Fisher; Ira J. Glockner; Phillip K. Honeycutt; Mark M. Peterson; William H. Bass. First Row, from L to R: William W. Watford; Kash C. Williams; Frank L. Everly; Stephen M. Velkoff, Herbert Gold; Roy A. Wright.

| Enlisted Men | |

| Lewis F. Albus | Kenneth B. Kemmerer |

| Peter J. Allegretti | Luther Kennedy |

| Ray Allison | Paul R. Kesler |

| Charles W. Anderson | Gordon A. King |

| Floyd E. Anderson | Orville Kingsley |

| Timoteo Apodaca | William M. Kinner |

| Charles R. Backes | Randall Krabill |

| Malvy H. Banks | Albert O. Kuckenbecker |

| Angelo J. Barranco | Arnold P. Lage |

| William H. Bass | George Landsdale |

| Earl W. Beaver | Vernon Lanier |

| Alex Bene, Jr. | William A. Latham |

| Hermon E. Bennett | Robert A. Laubscher |

| George M. Berry | James A. Leary |

| Louie E. Biles | Albert H. Lipe |

| Fred D. Blackwell | Jess L. Loman |

| Afred O. Boardsen | Andy B. Lowrey |

| Arnold Bolling | William Luecke |

| Lawrence Bruemmer | Claudy E. Lynn |

| Phillip Brower | Mirko Magulac |

| Harreld O. Bryant | John E. Mallory |

| Lange Butler | John L. Mantica |

| Lupe P. Calderaz | Everett B. Marks |

| Herbert Childers | Charles W. Maxson |

| Willard H. Chitwood | Chester R. McCreary |

| Azio Cioni | Lee M. McElroy |

| John H. Clark | Donald E. McLeod |

| John G. Coffland | William E. Meier |

| Frank J. Connelly | Ralph H. Melcher |

| James W. Cooper | Ebb Melton |

| Christopher Counts | Clarence E. Miller |

| Allen H. Cowart | Harlin Miller |

| Nathan R. Cox | Howard E. Miller |

| James J. Crafton | Jay Miller |

| Robert L. Cranfield | Lawrence E. Mobley |

| Benjamin F. Crouse | Edgar H. Moeller |

| Thomas Curran | Clarence A. Montijo |

| John D’Arcy | Cecil P. Moore |

| Abraham Davis | William Morris |

| Willis E. Delker | George Murdock |

| Ben B. Demny | George Nemet |

| Richard F. DeRosia | Roy D. Newton |

| Elroy E. Dettmann | Raymond Olson |

| Thomas P. Duffey | Thomas A. O’Malley |

| John E. Dunne | John R. Outman |

| Frank J. Ebert | Willie J. Palmer |

| Lawrence B. Eltrevoog | Albert M. Pederson |

| Robert G. Essler | William Pegram |

| Robert Evans | Mark M. Peterson |

| James L. Evatt | Henry P. Phillips |

| Frank L. Everly | Lancett A. Prestidge |

| Stanley J. Farnic | Stone Prewitt |

| Eugene R. Fisher | William S. Price |

| John A. Fletcher | Orvill H. Rahn |

| Robert A. Fletcher | Benny Ramming |

| Chester W. A. Foesch | Roy H. Ratliff |

| William D. Foss | Jack A. Rawson |

| Philip S. Fox | William H. Rea |

| James G. Frizell | Elmer F. Rensi |

| Richard D. Fullagar | John A. Reynolds |

| Kenneth J. George | William L. Rice |

| Robert E. Gettert | Leo Rittenour |

| William H. Gibson | John D. Robinson |

| Doyle Gill | Robert Rock |

| Frank B. Gillispie | John E. Shlosser |

| Durward B. Ginn | Wilbur J. Schneider |

| Stanley Girand | Fermin D. Scroggins |

| Ross Girratono | Earl W. Sequeria |

| Truman Glenn | Manford A. Shamhart |

| Ira J. Glockner | George A. Sigmon |

| Herbert Gold | Edgar Slagle |

| Nathan Gold | Henry T. Snider |

| Joseph Gonzales | Edgar E. Staha |

| William C. Gore | Verner W. Stratton |

| Dan W. Grider | James J. Sukash |

| Sidney F. Griner | George H. Tapella |

| Rosendo Gutierrez | Joseph F. Thompson |

| Frank L. Hales | William E. Thompson |

| Zeb Hart | Raymond Tolman |

| John Hartigan | Eldon Toogood |

| O’Neal C. Henson | Clinton J. Tryon |

| James P. Hill | Nelson E. Vaughn |

| John H. Hirtle | Stephen M. Velkoff |

| Frank M. Hite | Vernon H. Walls |

| Harold Hodgson | R.. M. Ward |

| Anthony E. Hollman | Bernard F. Washko |

| Paul Hollyman | William W. Watford |

| Leonard A. Holzapfel (Tec 4, 35217978) | Phillip O. Watson |

| Phillip K. Honeycutt | P. D. Weeks |

| Clyde R. Hovis | Frederick W. Weitendorf |

| Wilkie J. Huntley | David W. Whitt |

| Clarence H. Jenny | Robert F. Wideman |

| Cecil Johnson | Leslie M. Willaford |

| Harley M. Johnson | Hollis J. Willett |

| Henry L. Johnson | Kash C. Williams |

| Roy T. Jones | Bill G. Wills |

| Paul Joyner | Edward Wozniak |

| Stanislaw Jurski | Roy A. Wright |

| Stephan M. Katich | James R. Wyatt |

| Clifford C. Kautcher | Ranko J. Zarubica |

| Francis J. Keiley | Jacob Zupic |

This new Unit History looks at the World War Two service of the 34th Evacuation Hospital in the European Theater. The MRC staff are grateful for the generous offer made by Mary O’Malley, niece of Thomas A. O’Malley, who kindly donated a Booklet covering operations of the 34th Evacuation Hospital, allowing them to edit a concise history of this Hospital. Our sincerest thanks for her precious assistance.