200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement

(US Army Hospital Ship Louis A. Milne)

Unit History

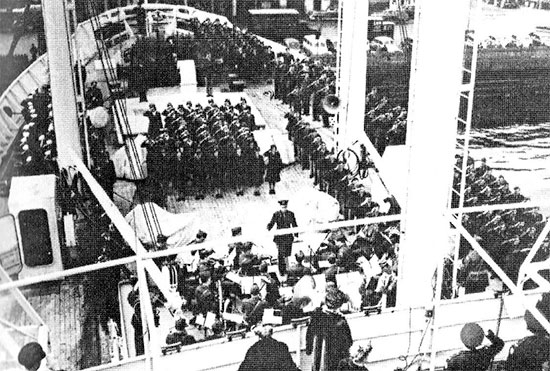

Official photograph illustrating the US Army Hospital Ship Louis A. Milne, taken after her commissioning, Friday, 16 March 1945, Boston, Massachusetts.

Introduction:

The S/S Lewis A. Luckenbach (vessel pertaining to the Luckenbach Steamship Company) freighter was first registered 18 April 1919, with Boston, Massachusetts, as her home port. The ship’s crew numbered 52 in total and could hold 12 passengers. Many of the large ships operated by the Luckenbach Line or under construction were commandeered by the United States Shipping Board in 1918. This particular vessel was built by Bethlehem Steel at its Fore River Plant, Quincy, Massachusetts. She was completed under the US Shipping Board contract and handed over to the Emergency Fleet Corporation. The EFC was established by the United States Shipping Board referred to as the War Shipping Board, on 16 April 1917, pursuant to the Shipping Act with the purpose to acquire, maintain, and operate merchant ships to meet national defense, foreign and domestic commerce during World War One (the Board and Corporation were abolished 26 October 1936 and their functions transferred to the United States Maritime Commission by the Merchant Marine Act (49 Stat. 1985) of 29 June 1936. Launching took place on 30 March and delivery was finalized 18 May 1919. The S/S Lewis Luckenbach was to serve its owners well for almost 25 years.

On 10 May 1944, the Lewis A. Luckenbach, was requisitioned by the War Shipping Administration, New York, with plans to convert her to a Hospital Ship (another freighter, the Dorothy Luckenbach, was equally converted to a Hospital Ship, and eventually designated USAHS Ernestine Koranda –ed). Conversion took place at the Simpson Yard of the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Company, East Boston, Massachusetts, and lasted some 10 months.

The USAHS Louis A. Milne, was officially designated a Hospital Ship 19 September 1944 by War Department General Order # 2, dated 5 January 1945 and officially placed under the protection of the 1907 “Hague Convention” (the Hague Convention X of 1907, represented the adaptation to maritime warfare of the principles of the Geneva Convention –ed). This implied that in order to be recognized and protected as a Hospital Ship, official certification under the terms of the Hague Convention was to be obtained. Moreover, the ship was to be unarmed, painted overall white and properly identified with the red Geneva Cross symbols, and duly registered with both friendly and enemy powers in accordance with the provisions of subject Convention.

Partial view of the official Commissioning, taken 16 March 1945. Foredeck USAHS Louis A. Milne; the band is playing the national anthem while all personnel stand at attention and salute.

Conversion & Commissioning:

The modified freighter (ex-Lewis A. Luckenbach) now included five decks, 12 lifeboats (135-person capacity each), and 6 life rafts. Side port widths were increased to 9 feet in order to ease loading (to accommodate litter patients and supplies). Eighteen-inch square wooden panels were fitted in the bottom part of every door to serve in cases of emergency (designated kick-out panels, easy to remove if doors could not be opened). The new Hospital Ship provided space for approximately 1,000 patients. Rooms and Officers’ quarters as well as Wards were all located outside on decks above the waterline (adjacent to cabins and relatively close to the lifeboats), which afforded much light and good ventilation and with passageways wide enough for the admission or removal of litter patients. The layout of the ship was such that an additional 300 patients could be cared for if necessary. A total of 6 Wards were available (the largest one held 68 beds), each with its Diet Kitchen. Seven (7) Isolation Wards with four beds each were set up at or just below the ship’s water line (isolation and mental wards were usually located aft) while other facilities such as Store Rooms, the Morgue, and the Laundry were placed in lower areas, including the hold. The 2 Operating Rooms, the Sterilizing Room, the Scrub Area, the Stores for Sterile and Non-sterile Supplies, the X-Ray Room and Dark Room, were located near the ship’s center (better stability). Clinical and administrative areas, including such spaces as the Dressing Room, the Pharmacy, the Laboratory, the Surgeon’s Office, the Medical Records, the Chaplain’s Office, the ARC Office, the PX, and Commissary, were on deck and above the waterline near the forward gangway or side-port entrance, to allow for easy access when in port. The top deck housed a large glass Solarium to benefit patients. Other facilities included a Lounge for ambulatory patients, a Recreation Room (furnished with a piano), and a Barber Shop (for shaving and haircuts). Deck chairs where patients could relax were available too (weather permitting), movies, games, and crafts were on board for entertainment of patients and crew (when off duty). A Public Address system disseminated music, news, and broadcasts. The Louis A. Milne’s official patient capacity was indicated as being 952.

Below deck, were 5 Refrigerator Rooms with food-capacity lasting 80 days. A separate Laundry Department handled approximately 4,000 sheets a day and ran on a 24-hour schedule. While the washing was done with salt water, the final rinse used distilled water. The ship was well-designed for long overseas trips. She consumed 20,000 gallons of oil per day and could run at maximum 14 knots (normal speed was 12 knots). Her fuel capacity allowed 38-days of steady steaming at full speed.

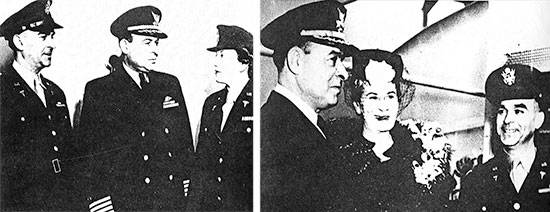

Official photographs taken during the Hospital Ship’s Commissioning. Left: Lt. Colonel Vincent J. Amato (Commanding Officer, 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement); Captain John W. Kirchner (Master, USAHS Louis A. Milne); Captain Geneviève G. Thorpe (Chief Nurse, 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement). Right: Captain John W. Kirchner (Ship’s Master); Mrs. Sue Madera Milne (Widow, Colonel Louis A. Milne); Lt. Colonel Vincent J. Amato (CO, 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement).

Officers were housed in large and comfortable staterooms. The Nurses were quartered in more compact and snug staterooms, three to a room. The rooms were furnished with a wash basin, double-decker bunks, and cupboards with drawers. Each room contained a porthole, a wall cabinet, a closet, and a bath to be shared. Private laundry facilities were available, including a washing machine. Even a sewing machine was included for possible repairs. Enlisted Men’s quarters were all located on the lower decks and contained three-tiered berths, each fitted with a reading light, but smaller and much less comfortable when compared to the Officers’.

Meals were conducted in shifts with each passenger assigned a specific time. Officers and Nurses ate in their own dining room. The ship’s crew were served meals in separate mess halls on one of the lower decks.

On 15 March 1945, the ship’s Master took the Louis A. Milne, out of Boston harbor early in the morning for her “shakedown run” (a term used by the Navy and Merchant Marine to test a ship’s performance usually during the last phase of construction, in order to look for any potential problems, it takes place prior to launching and commissioning, and on open water –ed) and return to port. After testing the ship’s capability for some 12 hours, all conditions of the trial run were deemed satisfactory, and she returned to Boston.

The United States Army Hospital Ship Louis A. Milne was officially commissioned on Friday, 16 March 1945, at the Commonwealth Pier, Boston, Massachusetts. Brigadier General Calvin DeWitt, Jr., TC, CO, Boston Port of Embarkation, presided the ceremony, in the presence of Lt. Colonel Vincent J. Amato and Captain John W. Kirchner. Special guests were Mrs. Madera Milne, widow of Colonel Louis A. Milne (1916-1945, former Surgeon New York POE, played a pioneer role in the development of the Army Hospital Fleet –ed), Mrs. George S. Patton (wife of Lt. General George S. Patton, Jr. –ed), and radio and recording star Miss Kate Smith.

Another photograph illustrating USAHS Louis A. Milne. Of special interest are the official Geneva Convention markings adorning the ship’s hull, and the positioning of the 12 lifeboats and the 6 life rafts on board.

(at the suggestion of The Surgeon General most Hospital Ships commissioned after spring 1944, were named for deceased Army Medical Officers and Nurses. Before they had been designated with names (e.g. Acadia, Seminole, Larkspur, etc), while the Navy gave theirs symbolic names (such as Hope, Comfort, Mercy, etc. please read our other Article > WW2 Hospital Ships –ed).

Prior to commissioning, Lt. Colonel V. J. Amato was extensively interviewed and a special article published on page eight of “The Lewiston Daily Sun”, dated 15 March 1945, stating among other details: NEW HOSPITAL IS LARGEST IN “MERCY FLEET”. The Louis A. Milne Has Trial Run – Has Beds For Nearly 1,000 Patients – HIGHLY EFFICIENT.

During World War Two, the Louis A. Milne, published a small newspaper, The “MILNEWS” on board ship, for the benefit of all. The ship’s newspaper was issued in mimeographed form and contained the latest news, briefs, poems, cartoons, stories, and general news about the war.

Organization:

The USAHS Louis A. Milne was operated by Captain John W. Kirchner, Merchant Marine, the ship’s Master (previously commanded USAHS Acadia –ed), with a crew of 145. The medical crew, consisting of the 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement, with Lieutenant Colonel Vincent J. Amato, MC, commanding, numbered 259 people (Major V. J. Amato, had previously commanded the 7th Convalescent Hospital –ed).

200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement – USAHS Louis A. Milne

11 Medical Corps Officers

2 Dental Corps Officers

4 Medical Administrative Corps Officers

1 Sanitary Corps Officer

2 Chaplain Corps Officers

1 Warrant Officer

37 Army Nurse Corps Officers

1 Hospital Dietitian Officer

2 American Red Cross workers

198 Enlisted Men

Although the United States Army had no Hospital Ships in the first part of WWII, efforts were made to build them, and The Surgeon General’s Office consequently drafted a Table of Organization (T/O) for a Medical Hospital Ship Company, as early as 1942. The basic document, designated T/O & E 8-537 dated 1 April 1942, provided for a unit of 12 Officers – 1 Warrant Officer – 35 Nurses – and 99 Enlisted Men. They were supposed to be able to care for 500 patients (for each additional group of 100 patients, a supplementary number of personnel consisting of 2 Officers, 4 Nurses, and 11 Enlisted Men was contemplated –ed).

In November 1942, the Surgeon General’s Office prepared a list of general specifications for Hospitals operating aboard ships (reference: Letter, The Surgeon General (Hosp Cons Div) for Chief of Transportation, Water Division, dated 26 November 1942, Subject: Specifications for Hospital Areas on Converted Transports, SG: 632-1 (BB) –ed). Early in 1943, recommendations were sent by the Water Division, Office of the Chief of Transportation to all ports in the ZI as a guide. Minimum standards called for a suitable surgical suite, minimal facilities for a pharmacy and lab, adequate toilets for the hospital area, safety measures and devices for isolation and mental wards, a small space for an x-ray unit, berths with maximum two tiers, and a number of beds as authorized by the Services of Supply.

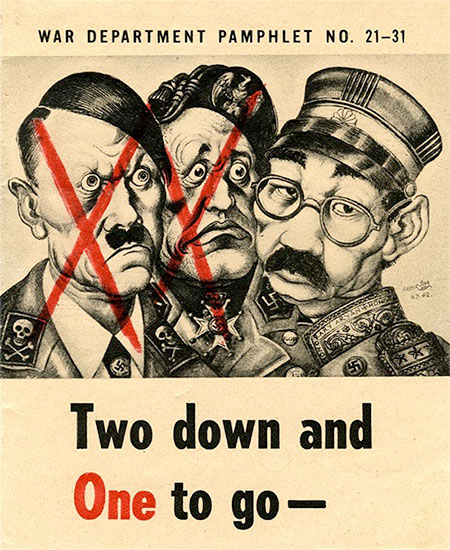

Prior to the official celebration of V-E Day, the War Department issued Pamphlet No. 21-31, dated 28 April 1945, ref. AG 461, 27 April 1945, US Government Printing Office: 1945-O-641346, with a clear message: “Two Down and One to Go”. It referred to the surrender of Italy and the recent breakdown of Germany, leaving the remaining Axis partner, Japan, to be beaten. The 26-page pamphlet also briefly discussed the streamlining of the US Armed Forces, the Adjusted Service Rating and Individual Score, and the Army Education Program. Pamphlet No. 21-31 was to be distributed to each individual in the Army concurrently or immediately after the showing of the WD Film “Two Down and One to Go”.

11 June 1943, the Joint Chiefs of Staff approved the following recommendations submitted on 30 May. They were listed as follows:

- The majority of the helpless fraction of sick and wounded patients were to be evacuated by Hague Convention-protected Hospital Ships when available

- A Conversion program limiting the type of ships to either slow-speed passenger vessels and / or EC-2 type cargo ships was to be started. Targets were set: the conversion of ships was to reach 15 Hospital Ships by 31 December 1943 – 19 Hospital Ships by 30 June 1944 – and 24 Hospital Ships by 31 December 1944

- The Army was to prepare to convert, crew, and staff the required number of Hospital Ships provided in the program

- There was to be a limitation of the outbound use of Hague Convention-protected Hospital Ships to the transportation of Medical personnel and supplies

In comparison to a Company, Separate Hospital Ship Platoons were later introduced with a much lower medical capacity and strength. A Medical Hospital Ship Platoon (Separate) as per T/O 8-534 dated 21 December 1942 only consisted of 5 Officers – 10 Nurses – and 40 Enlisted Men.

In order to speed up the construction of Hospital Ships, the Army began selecting transports and cargo ships for conversion under their new 24-Hospital Ship Program (which contemplated a total capacity of some 17,000 beds –ed). This brought about changes in the T/O resulting in a revision of the Medical Hospital Ship Companies’ personnel strength. A revision in fall of 1943 of the respective duties of both the civilian and military crews were agreed by The Surgeon General and the Chief of Transportation, and the Table of Organization for the Hospital Ship Companies was consequently revised. A new T/O & E 8-537T was published 7 December 1943, for the medical organization, now to be redesignated Medical Hospital Ship Complement. This particular issue authorized an aggregate strength of 184:

- 14 Commissioned Officers

- 1 Warrant Officer

- 34 Nurses

- 135 Enlisted Men

An updated version of T/O & E 8-537 was to follow on 3 March 1945.

Since a Hospital Ship Complement was assigned to each new or converted ship, the activation and training of such units was following the program of converting transports or other vessels to Hospital Ships. From the time, the first 4 were activated in the latter part of 1942 and early 1943, until the end of 1945, 25 additional Medical Hospital Ship Complements were organized and trained.

The provisional 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement was set to work at Rhoads General Hospital (named after Colonel Thomas Leidy Rhoads, MC, 1870-1940, designated US Army General Hospital by War Department General Order # 67, dated 14 December 1942, Utica, New York, wooden cantonment, ready for patients 25 August 1943, bed capacity 2,000, specialties: general medicine, general and orthopedic surgery –ed). The purpose was to give the personnel the opportunity to learn how to run a Hospital, by participating fully. Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men were instructed to work in the wards, do some clerical and administrative work, assist the current staff and help the patients when needed, also contributing manpower to keep the wards clean and spotless.

During fall of 1944, while waiting for the USAHS “Louis A. Milne” to become fully operational, the organization was stationed at Charleston Port of Embarkation/Debarkation, South Carolina (under command of Brigadier General James T. Duke; Charleston POE was in fact a sub-port to New York for troop movements -ed). The staff and personnel were kept busy with unloading incoming Hospital Ships and moving the patients to Stark General Hospital (situated in the Fourth Service Command, named after Colonel Alexander Newton Stark, MC, 1869-1926, designated US Army General Hospital by Letter A.G. 322.3, dated 9 January 1941, Charleston, South Carolina, wooden cantonment, ready for patients 18 May 1941, bed capacity 2,400, specialties: general and orthopedic surgery -ed).

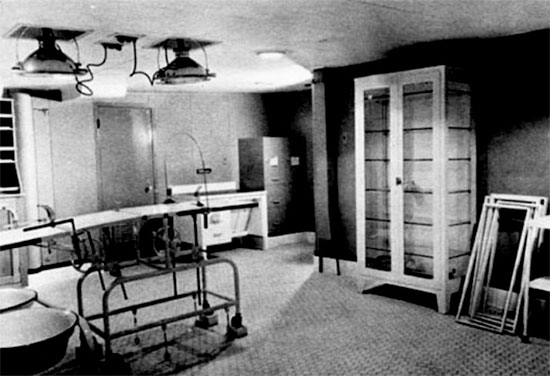

Dressing station on board the USAHS Louis A. Milne.

Since preparing Hospital Ships for overseas voyages and making preparations for debarkation of patients were specialized jobs, it had been decided by The Surgeon General that any such ships serving in the Atlantic should be operated out of Charleston Port of Embarkation. There was an advantage in having such vessels sail from and discharge their patients / passengers at a port that was not burdened with heavy troop or cargo movement (reason why New York was not selected). At this time, Charleston was not a very deep port, yet it was perfect for the coming and going of Hospital Ships, which would dock, disembark their load of patients, then clear the pier space, and wait for further orders. When no ship was expected immediately, it was back to basics, the main job being policing the 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement area, playing a lot of softball, following additional training, participating in drill and road marches, and even doing some duty at the Guard House.

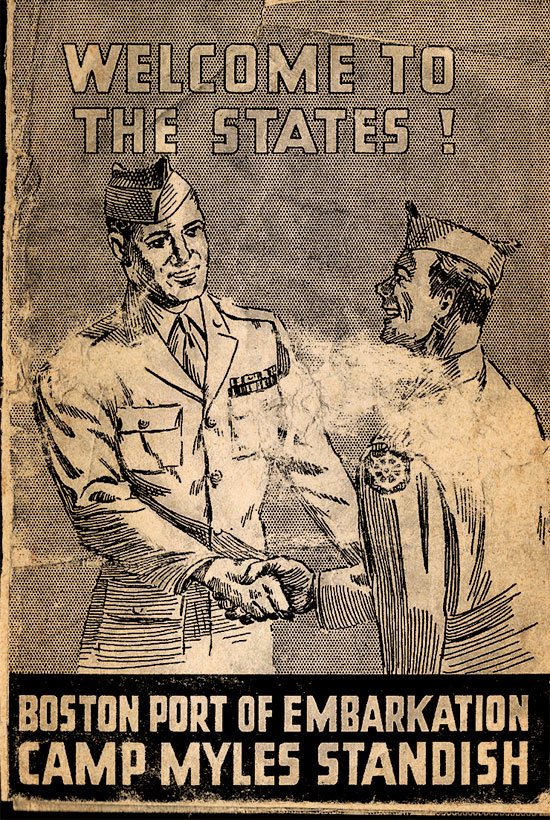

Late fall, the unit was transferred to another location; this was Camp Myles Standish, near Boston, Massachusetts (Staging Area for the Boston Port of Embarkation: overall acreage 1,485; troop capacity 1,298 Officers and 23,100 Enlisted Men –ed) where the 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement was formally activated. The Medical Officers including the Nurses were put to work at the Station Hospital. The Technicians were taking multiple courses in all kinds of medical and allied subjects. Other personnel were charged with administrative work, keeping records, the sick book, detailing the assignments, arranging passes and furloughs, preparing the payrolls, recording dedication to duty, etc.

During winter, the snow was quite high, and everyone was anxiously awaiting alert orders and news about a possible assignment, while the Louis A. Milne was being converted and outfitted at the Simpson Yard of the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Company in East Boston. It was while staging at Camp Myles Standish that the organization finalized preparations for the imminent movement overseas. Consequently the period was filled with receiving immunization shots, checking final clothing, drawing or replacing equipment, marking everything appropriately, and practicing embarking and debarking procedures, followed by a final physical test.

(Camp Myles Standish was a US Army camp located in Taunton, Massachusetts. It functioned as a departure area for 1,531.711 US and Allied soldiers and even contained a PW enclosure in World War II. In addition it served as a Receiving Station for troops returning home from Europe. Immediately after the war, it was considered as a potential site for the United Nations Headquarters. The city of Taunton was notified in June 1942 by the War Department that 1,500 acres would be requisitioned for use as a military Staging Area. The Camp opened on 8 October 1942 and was named in honor of Myles Standish (1584-1656), an English Officer who became Military Advisor to the Pilgrims for Plymouth Colony. Since huge numbers of military personnel would be passing through the installation, a complete Quartermaster Department was set up so an entire Division could be processed and prepared for deployment within a day. Troop trains would come in regularly from places such as Providence, Springfield, and Boston. The yard itself, run by the New Haven Railroad, contained about ten miles of track –ed).

Following receipt of alert orders early March of 1945 the unit was finally taken to Boston harbor where the ship was to be commissioned soon.

Major Command Officers – 200th Medical Hospital Ship Complement (incomplete)

Lieutenant Colonel Vincent J. Amato, MC > Commanding Officer

Major Edward A. Jackson, MC > Executive Officer, Chief Surgical Service

Major John H. Nesson, DC > Chief Dental Service

Captain Geneviève G. Thorpe, ANC > Chief Nurse

1st Lieutenant Maxine Prince, ANC > Chief Dispensary

1st Lieutenant Ann D. Crocker, ANC > Chief Neuro-Psychiatry Ward

1st Lieutenant Alfred M. Mosack, ChC > Chaplain

Surgical ward on board the USAHS Louis A. Milne.

Overseas Movement:

Shortly following her christening (16 March 1945), the new Hospital Ship left Boston POE with destination Avonmouth (Port of Bristol), United Kingdom, to pick up a first load of patients before sailing back to Charleston (the new hub for Hospital Ships situated in the Sixth Naval District –ed), South Carolina, ZI, where she arrived on 17 April 1945, with 938 sick and wounded. Upon arrival at Charleston, South Carolina, litter bearers and other personnel stood ready to help disembark the passengers, and many ambulances were waiting. The patients were then taken to the Hospital (usually Stark General Hospital, as a matter of fact the Hospital admitted 44,003 patients in a 9-month period starting 1 June 1945 to 30 September 1945 –ed), unless some of the cases required special treatment at one of the more specialized medical facilities. Hospital Trains were on standby, ready to take on any patients for further transfer. Whenever two, or more arrivals coincided, the ships would be tugged to a nearby pier to allow one Hospital Ship at the time to disembark its load of patients. Resupply and possible crew changes were handled separately.

SOP was as follows: the Service Commands used ambulances, buses, and Hospital Trains for transporting the patients from the docks to the Hospital(s). This depended on their physical condition and the overall distance to be traveled. To illustrate such movement the First Service Command normally used Hospital Trains to move incoming patients from the ships in the Boston Harbor to Camp Edwards (Falmouth, Massachusetts) and Camp Myles Standish (Boston, Massachusetts) Station Hospitals. The Fourth Service Command used ambulances and buses almost exclusively to transport patients from Charleston Port to Stark General Hospital. It must be noted that Ports continued to be responsible for debarking patients from ships (whether Troop Transports or Hospital Ships) for which they used their own personnel, including specially trained Port Companies and Medical Sanitary Companies as litter bearers, but if necessary, they would borrow EM from Service Command Hospitals. To save personnel and speed up operations, the Boston POE used wheeled litters to move patients on the piers. In normal circumstances, mental patients would be unloaded first, followed by ambulatory cases. Litter patients were usually debarked last because preparations to transfer them to litters could be made while other patients were being removed from the ship. As Ports gained experience in operations and improved procedures, the time required to unload ships decreased. For example the Charleston Port authorities cut the time from 5 hours at the beginning of 1944 to 2 hours by the end of the year and then even to only 1 hour for a 600-patient Hospital Ship during 1945. The Boston Port of Embarkation reported that on one occasion in 1945 as many as 1,958 patients, among them 287 litter cases, were moved from the ship to waiting trains in only 2 hours and 20 minutes!

Patients Evacuated From Overseas by Water and Debarked at Charleston Port, South Carolina

1943 > 1,128 Patients

1944 > 31,148 Patients

1945 > 41,299 Patients

Depending on the circumstances, loading / unloading of patients overseas consumed between 1 and 3 days. Liberty passes were seldom provided in view of the above activities which received absolute priority. The length of the ship’s stay in port sometimes allowed special visits by local authorities, or Medical Officers keen to visit a Hospital Ship. This could only take place while she was being loaded, unloaded, or resupplied and with the agreement of the Ship’s Master and the Officer Commanding the Medical Complement. .

On the very last trip to the European Theater, which took her to to Cherbourg, France, where she arrived 1 August 1945, the Louis A. Milne carried a large number of German Prisoners of War to the United States. The ship then returned to New York POE, with her passengers and prisoners, where she was fully resupplied and some minor crew changes took place. The date of arrival was 14 August 1945, the eve of the announcement of the Japanese surrender.

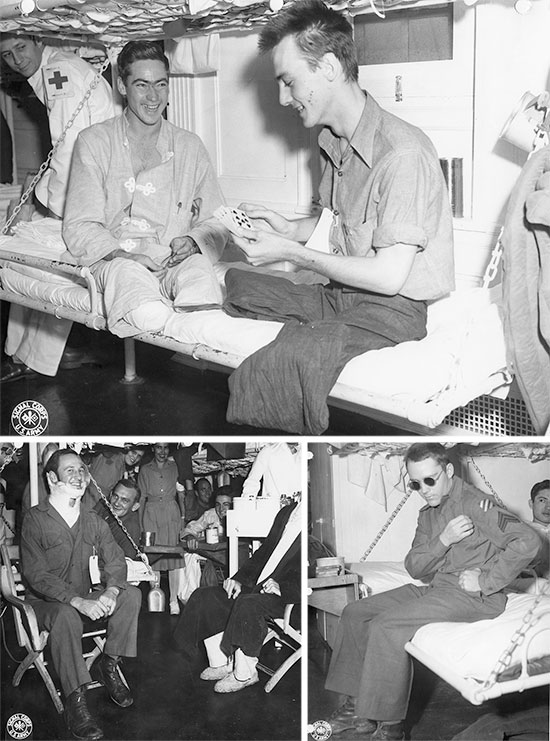

Miscellaneous war photographs illustrating patients aboard US Army Hospital Ships.

Since the war in Europe was over, the Allies’ attention now focused on Japan. It was now time for a new assignment. There was much work to be done in order to bring back sick and wounded from the Far East, including recently liberated American and Allied PWs. Following some modifications and adaptations, the USAHS Louis A. Milne, set sail for the Pacific by the end of August 1945. After leaving Brooklyn, New York, the journey went along some of the islands in the Caribbean, before reaching Cristobal, Panama 3 September 1945. The next day, the ship passed through the Panama Canal, from where she headed for Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, where some repairs were made. The voyage was rather enjoyable for all, as there were no patients on board. After spending some 9 days in Honolulu, the Hospital Ship continued on to Manila, Philippine Islands, which was reached on 19 October 1945.

Following the ship’s return trip to Oakland, California, major repairs were conducted at the General Engineering & Drydock Company’s yard, in San Francisco, California, from 6 March 1946 to 10 May 1946.

USAHS Louis A. Milne – voyages to the European Theater

Boston, Massachusetts, 19 March 1945 > Avonmouth, England, 30 March 1945

Avonmouth, England, 1 April 1945 > Charleston, South Carolina, 17 April 1945

Charleston, South Carolina, 6 May 1945 > Avonmouth, England, 19 May 1945

Avonmouth, England, 22 May 1945 > Charleston, South Carolina, 7 June 1945

Charleston, South Carolina, 17 June 1945 > Southampton, England, 29 June 1945

Southampton, England, 1 July 1945 > Charleston, South Carolina, 13 July 1945

Charleston, South Carolina, 20 July 1945 > Cherbourg, France, 1 August 1945

Cherbourg, France, 2 August 1945 > Brooklyn, New York, 14 August 1945

USAHS Louis A. Milne – voyages to the Pacific Theater

Brooklyn, New York, 27 August 1945 > Cristobal, Panama, 3 September 1945

Cristobal, Panama, 6 September 1945 > Honolulu, Hawaii, 22 September 1945

Honolulu, Hawaii, 2 October 1945 > Manila, Philippines, 19 October 1945

Manila, Philippines, 28 October 1945 > San Pedro, California, 19 November 1945

San Pedro, California, 22 December 1945 > Honolulu, Hawaii, 31 December 1945

Honolulu, Hawaii, 5 January 1946 > Manila, Philippines, 22 January 1946

Manila, Philippines, 7 February 1946 > Honolulu, Hawaii, 22 February 1946

Honolulu, Hawaii, 26 February 1946 > Oakland, California, 4 March 1946

Oakland, California, 20 May 1946 > Manila, Philippines, 14 June 1946

Manila, Philippines, 28 June 1946 > Yokosuka, Japan, 1 July 1946

Yokosuka, Japan, 3 July 1946 > Oakland, California, 17 July 1946

The War Department announced with WD General Order # 94, dated 1946, that the USAHS Louis A. Milne was to be decommissioned by 22 August 1946. She was finally scrapped in 1958.

Small folder issued by Army Services Forces, Boston Port of Embarkation, Camp Myles Standish, Boston, Massachusetts, “Welcome To The States !” intended for military personnel returning to the Zone of Interior, for either redeployment or discharge. This small document contained 5 pages, including a personnel message from the Boston P/E Commanding Officer and the Camp’s Commanding Officer, with a small map, and general information for servicemen and women.

The MRC Staff are looking for more operational data related to the USAHS Louis A. Milne and are still on the lookout for a complete Personnel Roster. All inputs appreciated. Thank you.