261st Amphibious Medical Battalion Unit History

Soldiers exercising at the obstacle course, Cp. Edwards, Falmouth, Massachusetts, ZI. Photo taken in 1942.

Activation & Introduction:

The 261st Medical Battalion was activated 15 June 1942, as per GO #64, Engineer Amphibian Command, at Cp. Edwards, Falmouth, Massachusetts (Antiaircraft Artillery Training Center). First Lieutenant Howard F. Conn, was assigned and joined, as per Paragraph 25, SO #12, Engineer Amphibian Command, taking over as Commanding Officer. On 30 June 1942, Captain Edward L. Tuckey, 54th Medical Battalion (Separate), relieved Lieutenant H. Conn, and assumed command per GO #1, 261st Medical Battalion. On 4 July 1942, a cadre of 219 EM was released from the 54th Medical Battalion per SO #23, and joined the 261st.

Organization

Company “A”, 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, was formed from Company A, 54th Medical Battalion

Company “B”, 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, was formed from Company C, 54th Medical Battalion

Company “C”, 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, was formed from First Platoon, Company D, 54th Medical Battalion

Headquarters, 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, was drawn from the newly formed three Companies

Major Merle E. Smith, MC, O-232723, transferred from Headquarters, Engineer Amphibian Command, was subsequently appointed Commanding Officer, 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, per SO #34, Hq, Engineer Amphibian Command, 17 July 1942. This arrangement held until November 1944, when Lt. Colonel M. E. Smith, MC, was transferred to Headquarters, Utah District, Normandy Base Section, and Major Daniel I. Dann, MC, took over command.

The 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion was organized under T/O 8-195, W.D., dated 23 July 1942, later amended to T/O 8-195S, 21 April 1943. The Battalion was assigned to and was an organic part of the 1st Engineer Amphibian Brigade (activated 15 June 1942 at Cp. Edwards, Mass. –ed), Engineer Amphibian Command (an Army organization –ed). In 1943, one such Medical Battalion was assigned one (1) per Engineer Special Brigade to provide initial medical support during landing operations in the immediate vicinity of beachheads including medical coverage in small boat evacuation to ships or base shore. The Amphibious Medical Battalion consisted of one Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment and three Medical Companies, each having a Collecting and a Clearing Platoon. Aggregate strength was 31 Officers and 394 Enlisted Men. A total of 56 vehicles and 7 trailers were authorized for transportation.

Changes in Designation:

Re-designated 261st Medical Battalion, per Letter, Headquarters, I Armored Corps, Reinforced, subject: “Change in Designation”, dated 12 June 1943.

Re-designated 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion at Caserta, Italy, 27 October 1943, under T/O & E 8-195S, dated 21 April 1943, per GO #79, Headquarters, Fifth United States Army, dated 27 October 1943. This plan was continued throughout the remainder of 1943 and 1944.

Movement Overseas:

View illustrating Port-aux-Poules, Oran region, Algeria. This is the place where the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion trained and the location of the Fifth United States Army Training Center in Algeria.

A month after the original cadre arrived, the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion left New York Port of Embarkation for the United Kingdom. On 6 August 1942, the unit sailed for the British Isles. The majority of the EM had been in the Army less than six months and many Officers on active duty less than one month! Many changes occurred during the early days spent at Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland. Personnel first had to get acquainted, as it was time to get organized and start intensive training for future operations. Because the foreseen equipment did not reach the organization in time, the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion was unable to make the North African landing with its parent organization. Early December 1942, the Battalion moved to a Staging Area at Birkenhead, England.

Mediterranean Theater of Operations:

On 8 January 1943, the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion sailed for North Africa, where it arrived on 11 January 1943. The unit was stationed at Arzew, Algeria. The three Medical Companies (A, B, C) rotated among the following three most important activities, while at the same time being kept busy with many varied jobs.

- The Battalion had at its disposal a total of 72 assigned and borrowed ambulance vehicles. The mission consisted in carrying to the various US Army Hospitals patients arriving at La Sénia Airport, Oran, from the Tunisian Front, and also in transporting patients from local Hospitals to the Port of Oran for embarkation.

- The Battalion operated a Clearing Station Hospital at Arzew, Algeria, with a capacity of 100 patients. It further rendered dispensary and dental care to other units stationed in the area.

- The Battalion trained at the Fifth United States Army Training Center, Port-aux-Poules, Algeria, in the Oran region, where invasion exercises and tactics were stressed.

On 11 July 1943, the majority of the men and equipment landed at Gela, Sicily (as part of the “DIME Force” in Operation “Husky”), in support of Seventh United States Army to handle the casualties and evacuation of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade beachhead over which the 1st Infantry Division had made the initial assault landing. The casualties were relatively heavy in this particular sector. However the presence of the 1st Medical Battalion Clearing Company, the two Provisional Collecto-Clearing Companies of the 51st Medical Battalion, elements of the 48th Medical Battalion (2d Armored Division –ed), and the additional 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion (initially attached to the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment –ed) provided adequate medical care and support. The beach group was supplemented by two Platoons of the 11th Field Hospital, seven Teams of the 2d Auxiliary Surgical Group, three Teams of the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group, and two Ambulance Platoons on loan from the 36th Motor Ambulance Battalion.

Following the beachhead phase the three Companies (in fact organized as Collecto-Clearing Companies –ed) ran small Holding Hospitals, each handling up to 150 patients. They were located at Agrigento, Gela, and Licata, were they primarily controlled and handled evacuation by sea to Tunis and Bizerte. On 19 August 1943, the Battalion was alerted for an immediate move to Bizerte, Tunisia, for assignment to Fifth US Army for what was later discovered to be the preparation for “Operation Avalanche“, the amphibious assault against Salerno, Italy, on 9 September 1943. However, the order was cancelled two days later (the unit being replaced by the 52d Medical Battalion, Separate) with the organization remaining in Sicily in bivouac. Up till the time of the alert the three Companies admitted 3,961 patients constituting a total of 9,201 patient days’ treatment. During this period Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment maintained continual trucking service, first carrying supplies to the frontline troops, and later transporting medical supplies from Licata to Palermo, Sicily, on behalf of Seventh United States Army (CG > Major General George S. Patton Jr).

On 19 October 1943, the Battalion sailed for Italy and on 24 October set up bivouac near Caserta. Except for some dispensary and evacuation work there was not much to be done. After turning in most of its equipment, the unit sailed for Naples, Italy, on 18 November and proceeded to return to the British Isles.

The 261st was officially transferred from MTO to ETO control 19 November 1943. After debarking, the organization settled at Truro, Cornwall, England, on 12 December 1943. From this time until the Normandy Invasion (6 June 1944) practically all the time was devoted to organizing, planning and training for the forthcoming invasion of the continent. Personnel arrived with almost no equipment, tired from its field operations, under strength, and with many sick personnel suffering from delayed malaria.

Mediterranean Theater of Operations – Official Campaign Credits

Sicily

Naples-Foggia

European Theater of Operations:

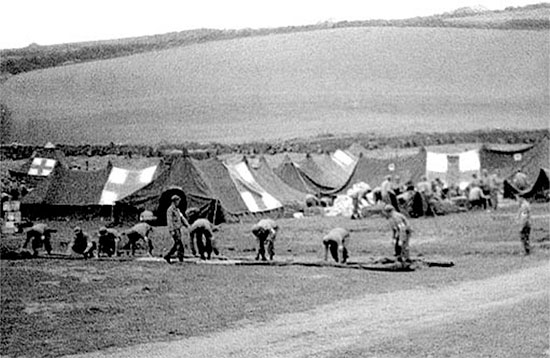

Group training and field exercises in Cornwall, England. 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion personnel are setting up the necessary tentage in the field. Picture taken some time early 1944.

United Kingdom

Once back in the United Kingdom, training of personnel, organization and preparation of equipment started all over again (all 1st ESB units had assembled around Truro, Cornwall, by December 1943) in view of the coming invasion. The training program was subdivided as follows:

- Physical Training – including calisthenics, marches, organized sports, litter exercises over obstacles, loading and unloading ambulances, etc.

- Training – including medical, chemical warfare, first-aid, and all the fundamentals necessary for a soldier.

- Group Training – Squads and Sections, with their own NCOs handling definite assignments, were stressed very much. Thus the leaders of the litter squads, the various sections of the Clearing Station, etc., were given practice at running their part of the SOP. This proved invaluable especially on the Normandy Beachhead where the majority of the medical Officers were too busy to do anything other than practice medicine or surgery. These NCOs had been taught to think for themselves and handle their own departments which proved invaluable during field operations. Having been specially trained for beach operations and with added experience gained in North Africa and Sicily, the unit refined its preparations for Operation “Overlord”.

- Technical Training – a great amount of time was spent in organizing adequate surgical sections. The Battalion conducted a school for Surgical Technicians run by their own Medical Officers and Noncommissioned Officers. Focus was placed on the development of a practical OR under tentage, sterile technique, administration of IV fluids and plasma, use of catheters and stomach tubes, and the preparation of sterile goods. This training more than anything else also paid dividends as the Officers were able to fully depend upon these EM to carry out many of the routine procedures. Before leaving for France a large quantity of equipment was sterilized and packed in waterproof cases.

- Company Problems Training – a Company would practice the setting up of its station and the admission, handling, disposition and/or evacuation of casualties, utilizing the clearing, litter and motor sections. The records group practiced the tagging and recording of simulated casualties.

- Division and Corps Problems Training – each individual Company participated in landing exercises with Divisional assault teams. There were endless field exercises, some with the 29th Infantry and some with the 4th Infantry Divisions. The entire Battalion took part in “Exercise Tiger” during the last part of April 1944. This closely resembled the planned invasion of France. These field problems (exercises) took place either at Pentewan, Cornwall, England, or Slapton Sands, Devonshire, England.

Cornwall, England. Personnel of the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion are installing their tents in the field.

- Special Problems Training – on 12 April 1944, Companies “A” and “B” took part in a special problem called “Splint”. It was run off in conjunction with the Medical Group of the 2d Naval Beach Battalion and the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment, 1st ESB. The exercise was supervised by Colonel Howard E. Snyder (XO > Surgeon, First US Army). This maneuver was considered very important by the Allied High Command with regard to the evacuation of casualties during the coming landing operations. 200 troops were used as simulated casualties. All phases of casualty handling from the time of admission to the reception of patients aboard ships for evacuation were demonstrated. The problem was run off before a large delegation of ranking Officers of both the United States and British Armies and Navies. The results demonstrated clearly that large numbers of casualties could be evacuated off a beach without disturbance to the other functions of the beachhead. Companies gained more practical value from this exercise than any other because they had available a large number of men to use as simulated casualties. Most previous exercises had given the unit experience only in movement of men and equipment and the setting up of a bivouac and station.

- Organization of Equipment – the equipment was adequate. The authorized T/E + additional authorization granted by First US Army staff enabled the 261st to carry on the required medical functions. This additional equipment included anesthesia, oxygen and suction apparatus, x-ray and fluoroscopic equipment (too little and used infrequently), an extra generator and additional tentage. As the need for surgery at the beachhead installations diminished and the surgical teams gradually left, the equipment was turned in to the Army Depots. This was a sound policy as extra equipment was needed only temporarily. Supply of expendables was always sufficient. There were enough wool blankets, litters and plasma at all times, and whole blood most of the time except between D + 2 to D + 4, when there was a serious shortage of litters and blankets. Due care was taken of the equipment to prevent unnecessary damage and loss. Some of the Battalion’s vehicles were unable to beach successfully because of high tides in Normandy and got submerged. However, they were all towed out the following day and after thorough cleaning and maintenance put back to use, with most of the equipment recovered. Battalion supply was kept busy especially by the three Companies as they were also responsible for providing medical supplies for the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. Later on they handled medical supplies for the Utah Beach Command which numbered over 25,000 troops. Each of the Collecto-Clearing Companies introduced many improvisations which were especially utilized in surgery. These included armboards and “Mayo” tables to fit on litters (used for operating tables), operating lights, drainage apparatus, etc. The steel racks used on the ambulance-jeeps to carry 4 patients were improvised by the Battalion Motor Section.

- Special Courses and Lectures – some of the organization’s Officers were able to attend special schools while in England. Classes included such subjects as plaster technique, neuro-psychiatry and shock. These proved valuable especially the course in plaster technique. Officers had to put on Tobruk splints, spicas, etc., while on the beach, and the refresher course was of great advantage to them. In general refresher courses were an excellent policy.

- Messing – at times this was a difficult problem. Each Company had only a single kitchen and at times had to feed up to 500 people at one meal, including personnel and patients. However, once functioning during the first week of the landing in France, they were able to serve hot meals to everybody. In the first few days it was coffee and “K” or “C” rations, but during the second week on the beachhead, personnel were able to start serving “B” rations as well.

- Throughout the year the amount of professional work performed by the Medical Officers varied greatly. Until June 1944 it was minimal since there was only routine sick call mixed in with training. On the beach it reached its peak. Cooperation and working together with the Auxiliary Surgical Teams was excellent. Two of the Teams supplementing the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion on Utah Beach had worked previously with the organization in Sicily and had requested that they join for D-Day. They belonged to the 3rd Auxiliary Surgical Group and were to be headed by Major Allen M. Boyden (Team 1), and Major Robert M. Coffey (Team 4). Four of the six attached Teams joined the Battalion nearly two months before “Operation Overlord”, and the other two over a month before it (subject attached units were Teams 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 under the respective command of Major Howard W. Brettell (Team 2), Major Frank Wood (Team 3), Major Walter W. King (Team 5), and Major Glenn W. Zeiders (Team 6 –ed). This proved very effective as it enabled the different units to get an overall knowledge of how they would function together during the landing and subsequent operations on Utah. Major surgery was performed by the attached surgeons as was the “final triage”. The 261st Medical Officers handled the pre and post- operative cases as well any minor cases. The only problem was that the unit did not have sufficient teams on hand. The surgeons worked too long a shift and were forced to run too high a backlog on casualties awaiting operative treatment.

- Dental Service – the dental clinic continued to function as an integral part of the Battalion, giving necessary dental attendance to all members of its command, other Army units in the area, and Allied and enemy PW personnel. At various times the Dental Officers were placed on TD with other units of the 1st ESB in order to provide the necessary dental care in those areas in which it was not available. Instructions in oral hygiene were given to all units serviced. A mobile Laboratory was attached during March and again for six weeks in July and August. These particular months were selected as Headquarters wanted to have all military personnel fit for the trying period of the planned invasion and the increased need for prosthesis was the natural aftermath. Unfortunately quite a few full and partial dentures were lost due to nausea and seasickness during the Channel crossing.

14 June 1944, Brigadier General James E. Wharton, Commanding General 1st Engineer Special Brigade, escorts Admiral Harold R. Stark, Commander US Naval Forces in Europe, on

an inspection tour of Utah Beach. Both Officers are being transported in a Truck, Command, 3/4-Ton, 4 x 4, WC-56, manufactured by Dodge Brothers Corp. (a Division of

Chrysler Corporation).

France

All the training and experience acquired by this unit in its travels prepared it for one of the most important missions to come: the handling of casualties and evacuation on Utah Beach, Normandy, France, during “Operation Overlord”, 6 June 1944 (between 3 – 7 May 1944, the 1st ESB, the 5th ESB, and the 6th ESB, were all busy with dress rehearsals and preparation of equipment for the invasion of Normandy, with some units training at the Assault Training Center, Woolacombe Beach, Devon, England –ed).

The 1st Engineer Special Brigade (activated 15 June 1942 at Cp. Edwards, Massachusetts, as the 1st Engineer Amphibian Brigade, with the 531st Engineer Shore Regiment and the 591st Engineer Boat Regiment, departed New York P/E 5 August 1942, arrived in the British Isles 17 August 1942, and landed in North Africa 6 December 1942, where it was re-designated 1st Engineer Special Brigade –ed) set up at Utah Beach in conjunction with the 4th Infantry Division which made the initial assault landings, and the 82d and 101st Airborne Divisions whose airborne and gliderborne troops landed beyond the inundated areas guarding the beach on the night before D-Day (the 5th and 6th ESB landed on Omaha Beach –ed).

The 1st Engineer Special Brigade (Brigadier General James E. Wharton, CO > May-June 1944 –ed) and their attached Naval Shore groups developed Utah Beach for the reception of troops, equipment and vehicles and for the evacuation of casualties. The main task of the Navy was shore-to-shore evacuation including cross-Channel transportation of all casualties to England. This was to take place with converted LSTs and British Hospital Carriers. As coordination with the Navy Medical Department was essential, 2 Officers of the 2d Naval Beach Battalion were assigned to the 261st as Navy Liaison Officers; 2 Officers established and operated First-Aid Stations on the main beach; and 2 more Officers served as Evacuation Officers on Utah Beach proper, with the necessary USN Hospital Corpsmen allotted to the three groups.

Normandy, D-Day

At 1730, 5 June 1944, the convoy with the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion aboard sailed for France and the continent. About 0930 personnel began the transfer from LCI # 513 to two LCMs for the landing proper. The first two groups of men landed between 1030 and 1100 hours.

Company “A” landed at about 1000 hours, followed by Company “C”, 2 hours later, while Company “B” landed on D + 1 around 2000 hours setting up next to Company “C” which it relieved for a period of 24 hours. On 1800 hours D-Day, major surgery was being done by the unit’s Medical Officers supplemented by attached Surgical Teams (the organization’s Collecto-Clearing Companies were formed by combining Litter and Ambulance elements with a Platoon from the Battalion’s Clearing Company, set up at crossroads just behind the flooded area). Working with the 4th Infantry Division’s medical personnel (4th Medical Battalion under command of Lt. Colonel Robert H. Barr, MC) and those of the Engineer and Naval Shore groups the 261st was able to handle all the casualties on Utah Beach. All patients were cleared through the Amphibious Medical Battalion. Working with the 2d Naval Beach Battalion medical sections (which landed at H + 1 hour with the assault waves), the unit controlled all evacuation to the United Kingdom. As there was no air evacuation on this beach in the early phase and very little even much later the organization evacuated almost all its patients in the chain of evacuation scheme. All definitive surgery was performed at the Companies until D + 5. After that the Field and Evacuation Hospitals gradually relieved them of that task (not before 10 June 1944 though). After the first two weeks the 261st was doing only the ‘overflow’ surgery; cases that occurred in the vicinity of their installations, or cases that ‘leaked through’ during the chain of evacuation. At this stage major duties consisted of holding and evacuating casualties. On 9 June, the British Hospital Carrier “Lady Connaught” (basic patient capacity 341) discharged medical supplies and six additional Surgical Teams for the Battalion, allowing for some relief for the unit’s original teams which had worked for 36 consecutive hours with but little rest. At the same time it took on board 400 wounded for evacuation to England.

Typical view of an Ambulance-Jeep used by personnel of the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion. The vehicle is a standard Truck, 1/4-Ton, 4 x 4, fitted with brackets to hold 4 litters. Of special interest are the bumper markings designating the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. Picture probably taken during field exercises in the United Kingdom.

Evacuation was accomplished chiefly by ambulance-jeeps augmented by DUKWs and trucks. Patients were sent primarily to LST (H) vessels (90 had been adapted for carrying and treating 200 patients, with heated spaces and bunk beds, outfitted with fully equipped operating rooms, to provide the necessary surgical and nursing care, and run by teams of 3 Medical Officers and 20 Hospital Corpsmen –ed) and also to British Hospital Carriers via LCTs and DUKWs. The former method was the fastest and also the easier on the patient as the journey to the Hospital Carrier involved moving the patient twice. First of all they were placed on vehicles, then the LCTs, and then after a rough ride out to the Hospital Carrier they were hauled aboard, all this with a lot of inconvenience and hazard. Some were loaded on board DUKWs at the Beach Clearing Station and transported directly to the Hospital Carrier. Where a long journey by boat was contemplated the latter ship proved a more comfortable ride. But on a short hop like the English Channel the limited and rapid handling of patients placed on LST (H) vessels more than compensated for the smoother ride. The speed with which the ambulance-jeeps could be loaded and unloaded was of great value in helping overcome the obstacles presented to LST loading by the fast rising tides. Their disadvantages were: the sickest patients rode better in ambulances, because during inclement weather, jeeps afforded no protection. Hence, it was of value to have several ambulances on hand in place of ambulance-jeeps. Coordination between Army and Navy Medical Officers was indeed essential to achieve a smooth evacuation system. It was up to the Naval Officers to find ships for evacuation especially in the early phases when the Beach Clearing Stations were filled beyond capacity. The group on Utah Beach under Lt. Ernest Reynolds, USNR, was both veteran and capable. They attached an Officer to each Company who kept in contact with the Naval Beach Station by “walkie-talkie” or courier. Thus, it was easy to coordinate evacuation policies and procedures. The 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion was able to get evacuation running except for a two-day period, on June 20-22, when a storm at sea prevented sending any casualties to the ships offshore. On 21 June, 691 patients remained at the three Collecto-Clearing Companies. However, the following day the storm subsided, and the organization was able to evacuate 515 patients, as the emergency was over. Though carrying on the important function of evacuation until the beach closed, the Battalion was of utmost value in the first four weeks of the landing, and especially during the very first week. An analysis of the number of patients admitted and evacuated illustrates the point:

| Date | Number Admissions (Cumulative) |

Number Evacuations (Cumulative) |

| 13 June 1944 | 7,245 | 6,533 |

| 20 June 1944 | 11,521 | 10,461 |

| 27 June 1944 | 13,814 | 12,670 |

| 6 August 1944 | 34,877 | 32,477 |

| 31 December 1944 | 42,551 | 36,045 |

During its first week on the Utah Beachhead, the Battalion averaged 1,035 admissions per day. The rate census gradually fell and the average daily admission rate for the first two months was only 571 patients. After that the rate decreased again. The American breakthrough at St.-Lô which occurred on 25 July 1944 required new evacuation points. It is evident that the handling of 7,245 casualties during the first week in France represented the peak of the unit’s accomplishments. Also, more definitive surgery was done on its patients during the first week than at any later time during the operation on the continent.

British Ambulance-Boats being used for evacuation of casualties from shore-to-ship. German PWs act as litter bearers.

Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment landed on D + 1 and immediately started to organize and run a medical dump for Utah Beach. Another worthwhile accomplishment was the clerical job of handling the numerous patient medical records and reports for the Battalion, as well as consolidating the records for the 1st Engineer Special Brigade which numbered 16,252 troops on the Beachhead. In August 1944, the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion was assigned by the Surgeon, Normandy Base Section, ComZ, to stage all Hospital units and all female personnel arriving over Utah and Omaha Beaches from the United States and the United Kingdom. The following were staged: 32 General Hospitals, 5 Station Hospitals, 1 Evacuation Hospital, 11 Field Hospitals, 2 Auxiliary Surgical Groups, 2 Motor Ambulance Companies, and miscellaneous groups of female personnel belonging to ATS, WAC, ARC, and other organizations.

1st Engineer Special Brigade – Assigned Medical Units

261st Amphibious Medical Battalion (Companies A, B, C)

1st Engineer Special Brigade – Attached Medical Units

Medical Depot Company

3d Auxiliary Surgical Group (12 Teams)

Throughout the unit’s stay on the Utah Beachhead, its trucks were handling supplies for the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. Later on they hauled supplies from the Medical Depot at Omaha Beach (M-403T Depot operated by the 31st Medical Depot Company) to Paris for the Surgeon, Normandy Base Section. Starting from August 1944 some of the Battalion’s ¼-ton trucks were used by the Surgeon, Communications Zone, and were stationed in various places such as Cherbourg, Paris and Rennes. This latter policy was in effect until the end of the year.

As the beach activities slowed down, Company “A” moved a short distance inland, near Ste-Marie-du-Mont and Headquarters. They set up a Clearing Station Hospital for mainly handling personnel pertaining to the 1st Engineer Special Brigade. During the last week of August 1944, they were joined by Company “C”. At this time Company “B” started to handle only the PW patients from the nearby enclosures, and this policy continued throughout 1944. On 11 September 1944, Company “B” joined the remainder of the Battalion. This arrangement lasted through November. At that time the bivouac and stations areas were becoming almost unusable because of the deep mud. On 11 December 1944, Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment, and Company “B” moved to Ste-Mère-Eglise, followed shortly thereafter by Company “A”. The latter ran a dispensary at Ste-Mère-Eglise and dispatched personnel to the First Platoon stationed at Valognes to augment the 61st Medical Battalion Clearing Station (subunit of the 5th ESB –ed) which was running a 200-bed hospital there. Company “C” moved to Granville during the last week of December. They took over the dispensary care for the surrounding area and also handled quarters’ cases. This arrangement prevailed until the end of 1944. Thus, the Battalion had in the meantime switched from a very definitive and important assignment in the summer to handling various odd jobs at the close of the year.

Partial view of a Casualty Collection and Loading Point on Utah Beach. This particular part of the beachhead was used by the 2d Naval Beach Battalion to coordinate the evacuation of casualties from shore-to-ship.

The 261st received a fairly large group of replacements in the course of February 1944, which resulted in 15% overstrength. They mainly came direct from the Zone of Interior, had completed basic training, and were mostly under 21 years of age. They augmented personnel strength and later proved to be excellent soldiers, though not highly trained Technicians. In general, they were the best replacement group the 261st ever received. During 1944 over 5% of the command was down with malaria. Some had suffered their first known attack in England or in France, while others were definite repeaters from the 1943 Sicily campaign. No civilian personnel were utilized during 1944. PW details were however of value during the latter months of 1944, mainly being involved in minor work details.

European Theater of Operations – Official Campaign Credits

Normandy

Northern France

Finale:

Having accomplished its medical task in Normandy, the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion was able to rest for a while during December. In January 1945, the organization was transferred from the Normandy Base Section to the Channel Base Section, France. On 18 January 1945, the move effectively took place. In the new area the four subunits were located as follows and performed the following duties:

Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment – Fécamp, France; in charge of routine administrative duties, of which Battalion Motor and Supply functions constituted the major occupation.

Company “A” – Le Havre, France: in charge of a running a hospital section in existing buildings with a capacity for 200 patients.

Company “B” – Cp. “Lucky Strike”, near Le Havre, France; in charge of operating a 150-bed tent hospital in the vicinity of St. Sylvain. This involved handling and caring for primarily transient troops whose hospitalization period would not exceed seven days. Running a large dispensary service and clearing all patients from this “Cigarette Camp”.

A medic from the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion, 1st Engineer Special Brigade (full arc on M1 helmet) checks the bandage of a wounded PW.

Company “C” – Cp. “Twenty-Grand”, near Duclair, France; in charge of running a 120-bed tent hospital , with duties similar to those of Company “B”.

Effective 28 January 1945, the 261st Amphibious Medical Battalion was disbanded (its former parent unit, the 1st ESB was shipped from Europe to the Zone of Interior in February 1945, and re-deployed to the Pacific Theater where it took over beach supply operations on Okinawa as from 13 April 1945 –ed) with its personnel and equipment subsequently used to form the 98th Medical Battalion which consisted of:

Organization – 98th Medical Battalion

Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment

761st Medical Collecting Company

762d Medical Collecting Company

763d Medical Clearing Company

764th Motor Ambulance Company

Statistics:

The Battalion existed for 31½ months. There was about a 25% change in personnel from the time the unit was organized until it was disbanded. Seventy-five (75) percent of its members served 30 months overseas and participated in 4 different Campaigns. Number of deaths in action: only 5. Number of missing in action: 0. Number of wounded in action: 17. Number of decorations and awards received:

261st Amphibious Medical Battalion – Official Awards

Legion of Merit 2

Bronze Star Medal 21

Purple Heart 17 (+ OLC)

French Croix de Guerre with Palm

Meritorious Service Unit Award

Presidential Unit Citation

Notes:

The 1st Engineer Special Brigade was sent from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, ZI, to the United Kingdom as a two-Regiment Brigade: one, an Engineer Boat Regiment (591st) and the other, an Engineer Shore Regiment (531st). Other organic units that joined the Brigade were an (Amphibious) Medical Battalion (261st), a Boat Maintenance Company (561st), an Ordnance Platoon (161st), and a Quartermaster Battalion (361st). When the 1st ESB re-deployed from the Atlantic to the Pacific, only the Brigade Headquarters & Headquarters Detachment were involved as the old Boat and Shore Regiments had been transferred and re-organized into other Engineer units after Normandy, remaining operational in the European Theater.

Partial view of Utah Beach after the 19-20 June 1944 storm. Wrecks and miscellaneous debris cover part of the Beachhead.

Some of the pictures illustrating subject Unit History are courtesy of Jonathan Gawne, author of “Spearheading D-Day”, Histoire & Collections, Paris, France, 1998, and NARA.

For a chronological review of Utah Beach Operations please click here.