612th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company Unit History

Cover illustration of the Book “C’est la Guerre” (This is War”) published in Bonn, Germany, 1945, 79 pages.

Introduction & Activation:

General Orders No. 54, Headquarters, Quartermaster Unit Training Center, Fort Francis E. Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming.

- Organization of Quartermaster Graves Registration Companies.

- Activation of Quartermaster Units.

1. Pursuant to telephonic instructions by Brigadier General Whittaker, QMC, Headquarters Seventh Service Command, Army Service Forces, 26 November 1943, the following named Quartermaster Units, having been ordered into active military service of the United States, effective 26 November 1943, and transferred to Ft. Francis E. Warren, Wyoming, by General Orders No. 125, Headquarters, Seventh Service Command, A.S.F., 26 Nov 1943, are organized in accordance with Table of Organization & Equipment, T/O & E 10-297, effective 27 November 1943:

609th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

610th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

611th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

612th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company

By command of Brigadier General Whittaker:

A.J. Seidl,

Major, QMC,

Director, Administrative Division

Left: Photo of Captain Thomas A. Rowntree, QMC, Commanding Officer, 612th QM GR Co (joined the unit 30 Nov 43).

Right: 1st Lieutenant Ellis V. Clack, QMC, Executive Officer, 612th QM GR Co (joined the unit 9 Dec 43).

Fort Francis E. Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming, Army Service Forces Training Center (acreage 94,874; troop capacity 665 Officers & 16,518 EM –ed). Captain Thomas A. Rowntree, QMC, from Amarillo, Texas, was the first Officer to arrive at Fort Warren (he would be appointed the unit’s CO –ed), followed by the 5 Officers and the cadre. His Executive Officer became First Lieutenant Ellis V. Clack, QMC, from Mendenhall, Mississippi. The Officers were recent OCS graduates, while the cadre were Corporals and Sergeants from other Companies who were to act as instructors during the planned training period.Little groups of recruits were slowly arriving, meanwhile the cadre had beds assigned, and had begun the task of teaching the new men the difference between the left and right foot. They also imparted some other little intuitional gems, the first and foremost being respect for the penalty for not saluting the staff cars that were almost roaming around, usually empty. During the first few weeks following arrival, there was little to do while waiting for the rest of the men to arrive and for the states to decide which of their loyal sons they could spare; but the cadre had the time well planned for their amusement at the recruits’ expense. There were so many little things to be learned with much concentration and effort that came as second nature to the old timers. First was physical conditioning, and by the time everyone had taken the hint that one was to get up when called in order to figure out which was left and right on their leggings, usually having to put them on twice. There was a mad scramble for the barracks’ door in order to make Reveille formation with much “blood and hair” on the frame to the delight of the First Sergeant! The Duty Roster kept by the First Sergeant (Roger D. Williams, from Washington, joined the unit 27 Nov 43, remaining with it until 29 Jun 45 –ed) was to become master of everyone’s waking hour, and part of everyone’s sleeping hours. In the Duty Roster were to be found the cold facts about just who had last done KP, Fireman, and Room Orderly; with Guard Duty added later …

Seeing that the area around the buildings was free of cigarettes and matches, was also one of the tasks of the First Sergeant. In the Army it was called; “policing up the area”. At any rate, most every morning, every man was out making the rounds of the locale and snipping all that didn’t grow, or was too heavy to move. After being lined up and enthusiastically been told by the N.C.O. what he wanted, he would say: “Go and get it, and all I want to see is derrieres and elbows!” – “If it moves salute it; if it doesn’t move, pick it up; and if you can’t move it, paint it!” was the proverb.

Training:

By the first of the year 1944, everyone had set himself to become some semblance of a soldier all day, and part of the evening. Life consisted of classes on Army organization, drill, calisthenics, more classes, and some field hikes to study such things as tank traps and the best way to wear a field pack. Some of the subjects were put across with the aid of movies and training films.

The Rifle Range was somewhat of a revelation to many. Those who were hunters thought they were well acquainted with a gun since they knew which end the shell went in and which was the business end. As usual Uncle Sam changed all of this, starting with the names. At home it was called a gun, but in the Army it was designated a rifle or piece. After learning the name of every nut, bolt, and piece with endless hours of looking down the sights at an imaginary foe, and firing imaginary bullets by the dozen, the sound of the first real shell just about deafened the men. The report itself was enough to give a man the jitters, but that and the contortions the Army insisted on going through while firing was all it took for these sadists behind the targets to frequently and joyfully run up that appropriately named “red flag”. The night before the big event in which all the shooters were to prove their qualities as marksmen, a pep talk was held to imbue the desire to qualify as an Expert Rifleman. For the next month, all went around enthusiastically interjecting into the conversation; “Let’s see the hands of all those who are going to qualify as Experts in the morning.” The following Sunday morning, the only day off, everyone made his way through the cold early morning to the rifle range, and built forbidden fires in the hopes of getting warm enough to recreate the drousy feeling so resentfully relinquished. The Company came through with flying colors, with First Sergeant Roger D. Williams achieving the highest score through the combined efforts of all those yet to make a rating, and a case of ammo.

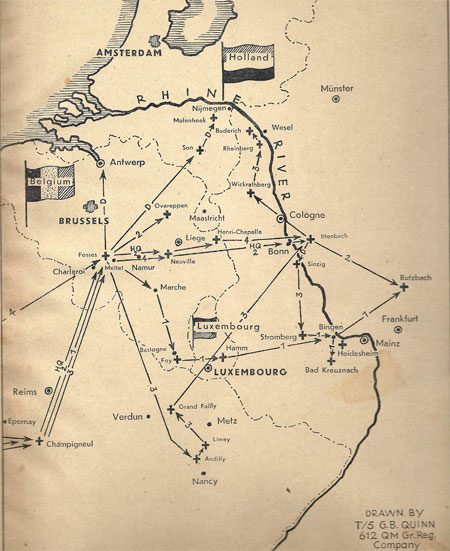

Partial map illustrating some of the sites where the unit operated on the continent (ETO).

The Infiltration Course was the Army’s attempt to give the men some experience at actual combat conditions. The men were instructed to crawl the length of a field between the relative safety of two trenches while several carefully watched .30 caliber machine guns fired about 2 feet above the ground. Big and heavy men left a regular furrow, so others got down in it and crawled behind each other, passing completely under several disinterested snakes. Sometimes personnel were led past a mine loaded with a reduced charge which went off after the men passed, spraying all the followers with a lot of oil, mud and slushy snow.

The Obstacle Course was the Army’s attempt to protect its vanity and live up to the Enlistment Posters showing how rugged it could make a man. There’s no doubt that it wouldn’t make a man or two, but it didn’t pay off if you consider the casualties suffered the first try. “Injured, in the line of duty, but not eligible for the Purple Heart” were John F. Higgins, with a broken heel; Harvey T. Trippel, with a banged knee; Charles H. Block, with a turned ankle, and 120 other men who were ready to surrender to anyone who could do the course in five minutes flat and talk German!

The weekly injections received made a woeful tale in itself. Practically every week and twice before paydays, all the men had to appear before a snarling gang of Medical Officers armed with syringes the size of grease guns, some of which were pneumatically driven. The needles came in all sizes and shapes. Part of the gang hummed merrily as it honed the needles for the next customer, and there was one half-back at the end of the line armed with a pair of tongs to remove the stub of any broken needles.

After Basic Training, came Technical Training. Personnel were divided into groups, each going to different Schools to unlearn all that had been acquired in civilian experience, and start from the beginning, the Army way. The Drivers were each issued an Army Driver’s License, and then ordered to march their class twice a day across some unexplored territory and through blizzards. Later on, it paid off with them taking trips in motor convoys to scenic places in Wyoming and Nebraska.

The Clerks went to yet another School, where they learned to type and prepare a Morning Report. The Draftsmen and Surveyors had their own little racket in which they were given to know that there are two ends to an Army pencil, and the usual practice was to start on one end with a knife in order to make it so it would write. After a week’s practice with SOP on pencil sharpening, they were presented with a piece of paper.

Some of the men were impressed with the fact that no one outside of Ordnance should try to disassemble an Army rifle, as one of the Ordnance people would then come and spend the evening replacing the parts that the more curious had had left over when reassembling their rifles. One of the men was sent to Buglers’ School.

While all this was going on, the rest of the men were learning how to operate a cemetery, the unit’s primary function. The Company Officers and cadre instructed classes on everything from the size of individual graves and types of dirt, to identification of enemy aircraft. One of the highlights of training was a trip to Denver, Colorado, to watch an autopsy and a taste of convoy-driving. The morning came in with a fog that made San Franciscians homesick, and went out with sub-zero temperatures. During the trip, the men learned from the old Army hands how to smoke without revealing their position to the enemy and those interested in preserving the sanctity of the Articles of War that state that there shall be no smoking in the rear of GI trucks! Autopsies were somewhat of a novelty to most of the personnel, with one or two turning slightly green and a certain surgeon’s son even passing out.

One evening the Company took to the fields for some more battle conditioning. After the usual gas and air raid alarms, things were going according to schedule, when the unit was attacked by an opposing force firing blanks, which caused considerable unrest since all the men had in line of defense were two flashlights and one compass. After the raid blew over, it was found that the map didn’t agree with the compass, which in turn didn’t agree with the tactical signs marking the course – the group was lost – and got back on intuition rather than on navigational equipment. As the organization’s training came to an end, the powers that be began to worry for fear that the 612th QM Graves Registration Company wouldn’t pass the examination. So, evening classes were instituted. The final examination was in the form of a ‘field’ problem. One snowy Saturday morning, the unit set off to fight the “Battle of Crow Creek” to the bitter end. It was all bitter, and as far as the Officers knew, it never ended as the exercise was called off when the Inspectors decided that they could best judge the men’s qualities over a hot cup of coffee than on a snow-blown hillside in zero weather. They did however linger long enough to see the Company set up a temporary cemetery, bring in the ‘bodies’, go through a gas attack, and be ever on the watch for enemy booby traps. They should have set up tank traps and dug individual foxholes, but the earth was too hard. “Crow Creek” was probably the most fought over creek in history, as every unit that came out of Fort Warren, had to put on a battle there!

Quartermaster Graves Registration Units trained by the OQMG:

1943 > 9 Companies

1944 > 6 Companies

1945 > 2 Companies

One bright morning, a Union Pacific man appeared in front of the Orderly Room, and this meant the men were getting furloughs. But there would be first a Center Parade, in wools. After proudly marching past the reviewing stand, the men were dismissed and received their furloughs – 7 days according to the papers – after being first confronted by MPs at the gate who gave everyone that longing look.

After furlough, classes continued, with many training films that started in the morning and ran until someone woke up to the fact that it was lunch time. Of course, calisthenics and drill went on as usual. The spirit was definitely improved and the Company began to show some character. POE (Port of Embarkation –ed) now became a subject of conversation and rumors.

Things began hard to get, with the excuse that they had been packed away or turned in. Interesting cases marked “TAT” (To Accompany Troops –ed), came to the Supply Room daily, and the rumors kept growing bigger and better with time and experience. Censorship became more plentiful and boring, and the Day Room became a clearing house for the rumors that floated back from the guys stenciling boxes or crates. Finally the men were given some more shots and pronounced fit for overseas travel.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

From the porters on the troop train leaving Fort Warren, some men were told that they were heading for Denver, but apart from moving toward the east coast no further information was collected. Sergeant Chester A. Garthwaite (joined the unit 18 Dec 43) then came through the cars wanting all the letterheads and anything referring to Fort Warren gone, censorship still applied. He was followed by First Sergeant Roger D. Williams who came through picking KPs and Guards. The cars resembled a safe from the outside, but the inside exceeded expectations (Pullman cars –ed). The windows were large, there was foot room aplenty, and the bunks were far more comfortable than those left behind in the barracks. They were built in a very businesslike manner, with no space wasted, even to the triple deck bunks. Up front was a boxcar with kitchen equipment, including two gas stoves for cooking, and the necessary rations fore some good eating. One man was selected from each car to help serve the food, bringing it on paper plates to the cars. There were volunteers for KP and they appeared particularly well fed too.

At Erie, Pennsylvania the train was given a big reception, with people lining the tracks and waving from windows. Card games, rumors, gossip, and small talk provided the only diversion from the panorama of passing scenery. Then the train paused in the middle of Buzzard’s Bay, and further proceeded across cranberry bogs to stop in the middle of a large field with no sign of any reception committee. Everyone picked up his pack, coat, helmet, rifle, and lined up for what was to be the longest walk: one that the personnel of the 612th QM Graves Registration Company would never forget. They walked 5 miles to the new barracks at Camp Edwards, Falmouth, Massachusetts (Antiaircraft Artillery Training Center, acreage 21,322; troop capacity 1,945 Off & 34,108 EM –ed). The men got off the train around 1600 hours in the afternoon and walked some 3 hours to the barracks, so it was about 2100 hours, after cold showers, some house cleaning, before they managed to scrape up enough cans of salmon, and hot coffee, and for the first time in the Army were told to take all they wanted!

Stations in the Zone of Interior – 612th QM Graves Registration Company

Fort Francis E. Warren, Cheyenne, Wyoming – November 27, 1943 > May 2, 1944

Camp Edwards, Falmouth, Massachusetts – May 5, 1944 > May 13, 1944

There were more and better shots, with the men being all set for the Port of Embarkation, assured of their physical well being. In fact life at Camp Edwards was no different from Fort Warren, with even more classes, inspections, marches, and drill. There were more words on censorship, and the Articles of War on desertion were emphasized. Priority was given to clothes and equipment, such as steel helmets, gas masks, with much new equipment making its appearance. There was a big variety in entertainment, with theaters and post exchanges around, and about three square miles of sand to explore. Company spirit began to show up again and a big beer party was organized in the mess hall.

Below deck on board the SS “John S. Ericsson”. Personnel in their bunks, trying to find a little comfort for the forthcoming Atlantic crossing.

With the last quart of vaccine shot in the men’s veins and another word on censorship, the 612th set off one foggy morning for the train. It was 5 miles into that Camp, but the hike back to the troop train was twice that under the added weight of all the new and extra equipment. After detraining, everyone stood around the docks in Boston wondering and waiting, while being served some hot coffee and donuts by the Red Cross girls. Then the men lined up and carefully remembered to answer with their first name and middle initial as the Quartermaster called the roll and everyone started boarding the ship, the SS “John S. Ericsson”.

Crossing the Atlantic:

The troopship SS “John S. Ericsson” (ex-SS Kungsholm, launched 17 Mar 28, Swedish-American Line, vessel bought by the US Government 13 Dec 41, converted for use as troopship –ed), departed Boston POE, Massachusetts, Thursday May, 13, 1944 with destination the United Kingdom (shipment code 1106-JJ –ed).

The 612th were herded below deck to the fifth stage, where they could hear the waves lapping against the sides of the boat. Berths were assigned and the use of the life jackets explained. After somewhat of a tiring and busy day, the men went below to try and find some graceful way to climb into a fourth tier hammock and sleep. There was considerable tossing and turning, mostly because the beds were made with a piece of metal pipe where most have padding. As the ship pulled out in the middle of the night, there were no bands or waving girls to say goodbye. There were five flights of steps to fresh air, and very little room to turn over.

The following morning, the group that was selected to go for breakfast first had to climb the five flights of steps to the deck, walk the length of the boat, go back down four floors to another waiting group who began the incessant punching of the meal tickets. The meals were good, though the men ate standing up to counters, Navy style, but they had such delicacies as ice cream and oranges. The trouble was that most men were land lubbers and thus out of their medium – many turned green like the leaves with the coming of spring – and meal tickets began to go unpunched. The overall attendance dropped off as the miles and waves increased.

Time on hand became the order of the day with such activities as poker, checkers, and even quiz contests filling the periods between meals and sleep. Men walked the decks and came back with reports of friends and relatives they had discovered hanging over the rail. During the crossing, the ship’s store of candy, cigarettes, and PX supplies were made available. Goodies such as candy bars, soap, razor blades, and even fountain pens made their appearance. Fire drills and abandon ship exercises were often held and each morning, at 1000, the brass on board took it upon themselves not to let anyone get away from the Army, by having an inspection. Everyone was to get out of the quarters which were then straightened, swept, mopped, with the last footprint carefully removed in anticipation of the visit by the Officer in charge. The ship’s crew had similar orders, and started chasing everybody from the decks with fire hoses so that they could wash them off. Although progress was made across the many miles of ocean, it remained unrecognizable, except for the characterless voice that came over the PA loudspeaker each evening, saying: “Attention, attention … blackout is now in effect … there will be no smoking on deck, and all outside portholes will be blacked out … all ship’s clocks will be advanced one hour, effective 0215.” The days then began to lengthen, and blackout didn’t go into effect until later and later in the evening. The men could now read on deck at midnight when approaching Liverpool and the British Isles.

Another touch of Army life was given in the form of some more vaccination shots. Medical personnel marched the whole boatload through sick bay and shot everybody. Two medics stood at the door shooting each man passing through, with two feeding the needles. Harry G. Natchke, paused a second too long in putting his shirt on, and got a double dose before he could get away. Another humorist carried his duffel bag past, and got it inoculated for typhus.

Everyone got his first taste of the English and the ‘gum chum’ racket as soon as the John Ericsson pulled into the docks at Liverpool. The lads were very receptive to the GI’s cigarettes and chewing gum, and the organization’s two-day stay in the harbor. Arrival date was May 25, 1944.

England:

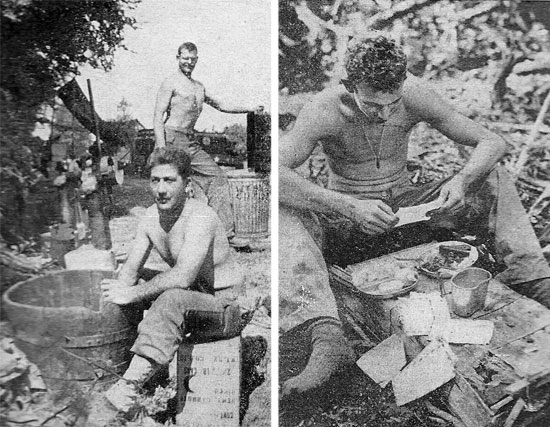

Left: Ste-Mère-Eglise, France, Steve Mikich (foreground) and John Knight (background) wash out a pail and an immersion heater while on KP.

Right: Ste-Mère-Eglise, France, mail call is much more interesting than battling the bees for chow.

Standard joke circulating on arrival: Question: “Got any gum, chum?” Answer: “Got a sister, mister?”.

The combination of rainy England and the fact that 612th QM GR Co had acquired the habit of moving on days the weatherman gave odds of rain found the unit debarking from the SS “John S. Ericsson” on May, 26, 1944, in a drizzle that everyone grew to think of simultaneously with the mention of the name “England”. Breakfast was already served at midnight. Everyone hit the gangplank at 0300, only to stand around with full packs in the rain with no sign of a shelter for miles. The train was ready at about 0600, luckily spirits were given a material boost by American Red Cross personnel who were distributing hot coffee, donuts, gum and candy. After entraining, the steam engine got started and took off at breakneck speed for a full fifteen miles of uninterrupted travel, stopping at a signal house, at a station, making its way past such places as Manchester and Oxford, and finally proceeding to a little whistle stop called Westbury, in the very heart of Wiltshire County.

After detraining, the men had to walk another 5 miles, burdened with their loads, with hunger whetted by a day on K-Rats, yet they practically climbed up to Hill Camp in less than three hours. Someone found out where the Morning Report was to be submitted, how many men were needed for guarding the first night, where to pitch the EM’s pup tents. Luckily some additional tentage was available and later two buildings would be set aside as soon as their occupants would leave. Using the utmost in diplomacy, it was decided that Headquarters, First Platoon, and part of Second Platoon would occupy the buildings; the remainder would be housed in pyramidal tents, with 4 men to a tent. A mattress cover with several bales of straw had been prepared, and after the long journey, most of the organization went to sleep from weariness.

Mail call took place the first day at the Post improving the general opinion of the place. This however lasted until lunch time, when the men were confronted with some 500 other souls all intent on going through the same chow line. As is necessary in the Army, all new arriving troops are given a period of “orientation” in which they are wised up to the ground rules and tipped off as to the next surprise inspections. One rare and sunny morning everyone was marched into the middle of a field ant put at ease by a very nice looking Major. Everyone took an immediate liking and admired Major Ely: this was due to the fact that he said that he had a sure fine method to beat us all home, and he presented the facts of life in England. However, the most disheartening news of the morning was the statement that the organization was still living according to garrison rules, and that individual beds would be made, Reveille stood, Retreat would be held, and that shoes would always be kept shining. Basic Training classes were once more instituted, partly to bring everyone up-to-date with the latest the war had to offer and partly to keep the men out of trouble. Hikes and calisthenics were organized and a class on camouflage and concealment given. Because of the air raids, a shelter was dug in front of the buildings, but the effort went to naught as it filled with water the next day.

The troop basis for the First United States Army included 3 assigned QM Graves Registration Companies and 2 more on loan from the Services of Supply. Initially one Platoon was attached to each of the amphibious assault Divisions and each Engineer Special Brigade. The “Neptune” build-up schedule called for 18 QM Graves Registration Platoons to be ashore by D + 12 to support a force of 11 Divisions. The Graves Registration Division, Office of The Chief Quartermaster, was responsible for the training of such units in the UK in preparation for the cross-Channel assault. Supervision was in hands of Major Maurice L. Whitney. The Officer later (May 44) became Graves Registration Officer, Forward Echelon, ComZ, and was succeeded by Lt. Colonel Arthur C. Ramsey.

The 612th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company was now assigned to the Advance Section, Communications Zone (ADSEC, ComZ) and given some priority on operational equipment. The unit’s drivers were first to leave one morning for Taunton, to pick up five ¼-ton jeeps, 12 ¾-ton weapon carriers, and 1 2 ½-ton truck. After a considerable period of training, on the left side of the road, many hours were spent, stenciling numbers and code colors, breaking in the engines, learning how to fix minor repairs, after which they were ready to tackle the job of rounding up and collecting the unit’s equipment. At this time, England was a maze of General Depots, each of which had a certain item to complete the authorized T/O & E. As usual there were a few inconsistencies but everything gradually fell into place. The clerks had meanwhile found work behind typewriters, and others were helping to bale Signal Corps wire spools. As D-Day approached, with a possible movement across the Channel, operations went on a 24-hour a day schedule, and some of the unit’s EM were lost for a while, attending business somewhere else.

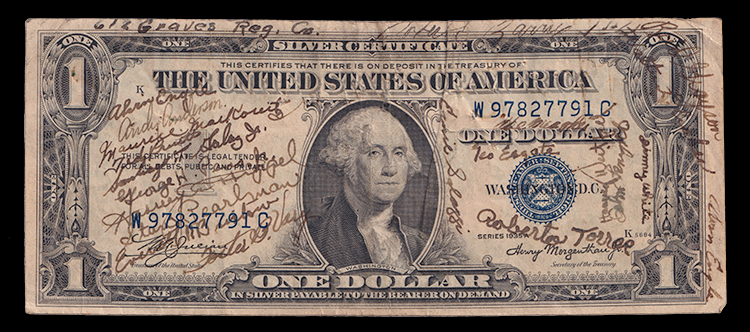

“Short snorter” 1 Dollar bill (Series of 1935) signed by the following members of the 612th QM GR Co:

Alvin C. Anderson, Robert E. Barry, Everett R. Bristow, Walter Craker, Alvin Engle, George Esgate, Santiago T. Galaz, Reid Grayson, John Knight, Maurice Markowitz, Joseph C. Meagher, Stanford H. Pearlman, George H. Pens, Ted Pruitt, Americo E. Solazzi, Roberto E. Torrest, Harvey T. Trippel, Foster B. Vary, Harvey W. Westfall, James D. White.

Courtesy of Colleen Ohara.

The 612th’s “Top Kick” (First Sergeant R. D. Williams) and some other NCOs made a trip to London, only to come back looking years older bearing tales of “buzz-bombs” that had eliminated all features of one city block and the bus they missed during their visit. The organization was alerted 4 July 1944 with the news that everyone was to move into pup tents, as all units had to do before leaving for the continent. Waterproofing the vehicles in anticipation of an amphibious landing became the order of the day as the drivers studied the manuals. Morning Reports were written a day in advance, watertight seals were rechecked, and the unit finally headed for the Marshaling Area the morning of July, 21, 1944. The arrival followed the same SOP as was customary in other places; the guard detail was set up, a depository for the Morning Report found, and the pyramidal tents assigned. Chow lines were not as long, as there were scattered mess halls all through the wooded area that sheltered in natural camouflage the thousands of men that flowed in and out in a steady stream. The 612th had to wait for two days waiting for the loudspeaker to call its code number saying that everyone was to leave for the boat. During this period, emergency K-Rations were distributed, French ‘Invasion’ currency issued, and two clips of .30 caliber Carbine ammo supplied. It was raining, as usual, at the time of departure. The elation at seeing a large town like Southampton was quickly subdued by the barrage balloons and antiaircraft artillery guns. The docks sheltered the men from the pelting rain as they watched the cranes load the vehicles. There were 7 or 8 more hours to kill with rain coming down full force, before the unit was ordered to board. Meanwhile services were held by a Chaplain waiting for the same boat. The vessel which was to carry the organization across the Channel was a Liberty Ship. Around 0800, all personnel answered to the roll call, and counted the thirteen steps up the gangplank. Sometime in the middle of night, the ship moved down into the English Channel to wait for the rest of the convoy. The first morning at sea, First Lieutenant Richard C. Steegmuller (from Newburgh, New York, joined the unit 11 Dec 43), as Mess Officer, found a place to steam heat the cans of C-Rations. The menu became somewhat dull, with canned meat and vegetable stew for breakfast – hash for dinner – and meat and beans for supper. Some of the most energetic men hit the Navy for both board and room by helping with KP, and returned with a satisfied grin on their faces and great tales of fine steaks. With nothing to do, card games received renewed attention, and haircuts were organized.

The anchor was eased down off Utah Beach, Normandy, France, and then began the more colorful, or ‘sitting duck’ phase of the voyage. Antiaircraft fire at the nightly enemy intruders was like a Fourth of July celebration across the horizon. In the afternoon, the ship dropped anchor about a half mile off Utah, and the organization’s name was entered on the Harbor Master’s list of applicants to debarkation. That same evening, searchlights suddenly started their silent prodding for the first visitors, the boats around the Liberty Ship opened fire with their tracers, deck sleepers rolled over to watch the spectacle while others went down to get their steel pots, which were definitely a necessity. The concentration of lights, tracers, and cannon fire got one enemy plane directly overhead. It exploded in a blinding flash and as the fragments began to shower the deck, there was a unanimous rush for the ladder.

The next morning a Harbor Master’s boat came alongside with the news that the ship was at the wrong beach, and that it should proceed east, to another Beachhead, designated Omaha. After another night full of blinker signals and shelling on the shore, it was decided that the 612th was ready to land the next morning, concluding the Channel crossing after a number of days at sea. The men climbed down a rope net over the side and into an LCT which took them to shore. It was July 28, 1944. Vehicles were waiting and it was back on the right (correct) side of the road. The motor convoy took the organization near the town of Isigny, which became its first bivouac on the Continent.

France:

The Company’s first home in France was a field near the town of Isigny, Normandy. The men arrived about noon and unpacked their equipment under the shelter of trees and underbrush, called hedgerows. The kitchen was soon set up for a meal and all the trucks were parked with an eye for camouflage. No one dare light a cigarette during darkness, pup tents were set up, camouflage nets placed over them, and all was ready for the first night in the field. Everyone crawled out when the first antiaircraft gun let go. It wasn’t quite dark enough to see the tracers, but the puffs of smoke kept the men interested. The coming of the evening dew gradually dampened everyone’s curiosity, so all retired to sweat out the gun emplacement in the next field, and the idea of falling shrapnel didn’t make the ground any more comfortable. With darkness came another round or two from the guns. The bivouac was situated on a hilltop that circled a valley full of ack-ack, and a depot lighted up for night operations. Someone came around warning the men that if the planes did appear, not to fire at them. Firing on observers, would bring back enemy planes to drop bombs.

As the last light of the sun was dying from the sky, the low drone of an engine was heard and searchlights began dissecting the sky. The tracers all focused in one direction as an enemy plane approached the depot. On his first pass, the attacker dropped some flares. The visitor’s second pass at the valley brought forth twice as much light and noise, but apparently pictures were all he was after, and he headed for home. Many of the personnel stayed in the ditches and foxholes and the night passed without another warning.

Villeneuve-sur-Auvers, France, Enlisted Men Steve Mikich, Fred S. Garcia, John Knight, Stanford H. Pearlman, Everett R. Bristow, George B. Quinn, and Lt. Robert E. Barry

before going for a swim.

The following morning, a group of men was selected to begin its first work as Graves Registration personnel. They were sent to a nearby field, where some colored servicemen had made the mistake of firing at the visitors of the previous night and had been the recipients of two delayed-action bombs. Identifications were made, the bodies collected and removed to La Cambe cemetery.

After policing all the local fields for debris and shell fragments, and listening to a class on how to recognize landmines and booby traps, with emphasis on unexploded ordnance, the group was ready for bed. Unfortunately, living near a gun emplacement just wasn’t conducive to sleep.

The order to pack and move to the first cemetery was received with unanimous acceptance the next day. The 612th packed its individual pup tents, towels, and toothbrushes, and set off for the town of Ste-Mère-Eglise, arriving there in time to take over from the First United States Army on July 31,1944.

For the D-Day landings a number of QM Graves Registration Platoons were attached to the following

(incomplete) units:

1st Platoon / 603d QM GR Co > 4th Infantry Division

2d Platoon / 603d QM GR Co > 9th Infantry Division

3d Platoon / 603d QM GR Co > 90th Infantry Division

4th Platoon / 603d QM GR Co > 82d Airborne Division

1st Platoon / 606th QM GR Co > 1st Infantry Division

2d Platoon / 606th QM GR Co > 29th Infantry Division / 2d Armored Division

3d Platoon / 606th QM GR Co > 2d Infantry Division

4th Platoon / 606th QM GR Co > V Corps

2d Platoon / 607th QM GR Co > 5th Engineer Special Brigade

3d Platoon / 607th QM GR Co > 6th Engineer Special Brigade

4th Platoon / 607th QM GR Co > 1st Engineer Special Brigade

2d Platoon / 608th QM GR Co > XIX Corps / 29th Infantry Division

3d Platoon / 608th QM GR Co > 3d Armored Division

4th Platoon / 608th QM GR Co > 30th Infantry Division

1st Platoon / 3041st QM GR Co > VII Corps

2d Platoon / 3041st QM GR Co > VII Corps

First Operations:

The men sought out the foxholes dug by the previous occupants and put their pup tents right over them; combining tent and foxhole in a most interesting fashion.

The breakthrough at St.-Lô was going on at the time and the evening sky was full of heavies and fighters on their way to pave a road for the advancing armor. Much to everyone’s dismay, the tranquility of the evening was shattered by an even larger gun than the one they were near previously. Those hedgerows were interesting but also dangerous, they were impenetrable and it was always difficult to know what was going on the other side. At about 0500 the next morning, everyone was awakened by the aircraft engines, and at about 0600, a squadron of fighters took off over the bivouac from neighboring fields. All day they went on shuttling away between the frontlines and the temporary landing ground. About noon, a tank outfit started through, making a deafening noise all afternoon and night.

Booby traps were the big worry. Everyone was forbidden to make unnecessary trips through the adjoining fields as they hadn’t been cleared. Evening poker was in again and the medium of exchange was no longer Invasion currency notes but a bottle of cider. At the same time the 612th learned to respect a new stuff called “Calvados” (some men even compared it to 80 or 90 octane gasoline). Bees and insects were thriving on the mashed apples on the ground and the jelly received for dinner. It became impossible to lay a piece of bread and jelly down without the bees taking it over. The only way was to set some bread with jelly aside for the visitors and try eating without being discovered.

One warm sunny day, an Officer drove up in a Command & Reconnaissance Car – he was Captain Gibbs, who had been in Europe during the last war, looking after the cemeteries. He looked over the situation and pronounced the verdict that things weren’t going so well! Firstly, he’d like to see all the wooden crosses painted with a fresh coat of white paint and the names stenciled in black on them. Aligning the crosses was another matter the TMs didn’t touch upon. It became the responsibility of the Surveyors and Draftsmen, who armed with transits, tapes, wires, sledge hammers and other tools, set out to learn what it was all about, the hard way. The final and only method was to use four men to do it: one on the hammer, one holding the wooden marker, the other two giving directions from vantage points at either end of the vertical and horizontal rows. Disinterments were started in order to collect and transfer the remains to the cemetery. A first crew went to Montebourg with First Lieutenant William H. Staub (from Princess Anne, Maryland, joined the unit 11 Dec 43) to look for some GIs buried in the fields by the hastily advancing troops. As it became apparent that there weren’t enough people to handle the job, Second Lieutenant Robert E. Barry (from Long Island, New York, joined the unit 9 Dec 43) requisitioned some German PWs.

On August 7, 1944, Fourth Platoon received orders to take over the cemetery at St.-Laurent (designated Cemetery No. 1 –ed) overlooking the beach where the 612th had come ashore. Arriving in the late afternoon the same day, the men put up their individual tents in a temporary fashion and moved into some of the existing foxholes (they would turn into bathtubs in lieu of bedrooms with the rain). Meanwhile, another temporary cemetery had been made (St.-Laurent Cemetery No. 2 –ed) by digging trenches with a bulldozer. It was however closed June 10 with all bodies disinterred and removed to St.-Laurent Cemetery No. 1. Many temporary burial grounds were set up since prompt disposal of body remains were imperative for sanitary reasons. Some units made emergency burials setting up temporary cemeteries using their own labor as well as French civilians (Poupeville & St.-Martin-de-Vareville, 4th Inf Div; Blosville, 82d Abn Div; Hiesville, 101st Abn Div; Ste-Mère-Eglise; La Cambe; Orglandes; St.-Laurent; Marigny; St.-Corneille; St.-André; Solers, etc. –ed). After the breakthrough at St.-Lô, activities at the cemetery gradually slowed down and the men were now busy with disinterments from the nearby fields. It took a five-man crew to take the recovered personal effects to Cherbourg. While in the field, recreation often consisted in watching a movie or visiting a Red Cross club for the Engineer; Dock, Port, and Depot personnel operating at the Beachhead.

On August 9, 1944, Third Platoon left the Company at Ste-Mère-Eglise (opened 6 Jun 44) for La Cambe (opened 8 Jun 44), where they built some shacks of wood from vehicle crates donated by an Ordnance Company. In the line of operations, burials and disinterments kept the men busy. Third Platoon were soon relieved by a Composite Company consisting of 1 Officer and a few men who were to maintain the cemetery at La Cambe and manage the hired civilian labor.

Headquarters, including First and Second Platoons also moved from Ste-Mère-Eglise to a temporary cemetery near recently liberated Marigny (opened 31 Jul 44), by motor convoy, on dusty back roads. Upon arrival the men set up their pup tents and dug the necessary foxholes into another orchard (with apples and bees). Operations at Marigny were confined to beautification and disinterments, with a few burials of diseased patients coming from the hospitals in the area. The German part of the cemetery was turned over to First Platoon, with Second Platoon becoming responsible for the other side of the dividing road. The remainder of the men guarded PWs (labor details), aligned the wooden crosses and laid out small roads around the plots. The rainy season set in and soon operations were all but halted in favor of keeping warm and dry.

On August 28, 1944, First Platoon took off for St.-Corneille (opened 16 Aug 44), near Le Mans. The men were split into two groups, one headed by Joe Saddoris took over the American cemetery, and Joe Rodewald took the German one. Beautification began with the help of contracted civilian labor, who, together, brought about a big change within a few weeks with roads, walks, and well-aligned crosses. A flag pole was selected and prepared.

Warm summers and evenings found First Platoon enjoying a rest camp, with Second Lieutenant Gerald H. Myers (from Beverly Hills, California, joined the unit 21 Mar 44) allowing the men to enjoy steak dinners in nearby Montfort and swimming in the pond below the paper mill. Champagne being relatively cheap by US standards ($ 2.00 per bottle) was purchased for celebrating birthdays.

On September 7, 1944, Headquarters plus Second Platoon made the move to Villeneuve-sur-Auvers, near Etampes. The new bivouac area was in the middle of a deep forest, near a stone quarry, and in an apple orchard. The cemetery was small and apart from the occasional disinterments and burials there was not much work. The town down the hill was very receptive to American soldiers and before long, practically all the men from Second Platoon had a home and French family to visit, with many dinners and pleasant evenings. All the other Platoons stopped in on overnight visits. Third Platoon was sent to Champigneul (opened 1 Sep 44); First Platoon was on its way to Solers (opened 30 Aug 44); Fourth Platoon moved to the cemetery at St.-André (opened 24 Aug 44). Most cemetery operations consisted in putting up and taking down the Stars and Stripes, so people got their rest. All efforts were concentrating on seeing Paris, and there were always enough volunteers for such details as taking in the mail and personal effects to the French Capital; in fact the trucks were usually full of sightseers on those trips.

Status of American Cemeteries in France – September 12, 1944

Saint-André – 589 burials (374 American + 7 Allied + 208 Enemy)

Solers No. 1 – 244 burials (238 American + 6 Allied)

Solers No. 2 – 149 burials (149 Enemy)

Saint-Laurent No. 1 – 5,133 burials (3,760 American + 83 Allied + 1,290 Enemy)

La Cambe – 5,843 burials (4,227 American + 1,616 Enemy)

Blosville – 4,670 burials (4,670 American)

Saint-Martin – 452 burials (260 American + 3 Allied + 189 Enemy)

Sainte-Mère-Eglise No. 1 – 3,213 burials (2,200 American + 13 Allied + 1,000 Enemy)

Sainte-Mère-Eglise No. 2 – 4,139 burials (4,109 American + 30 Allied)

Orglandes – 6,074 burials (6,074 Enemy)

Marigny No. 1 – 2,481 burials (2,479 American + 2 Allied)

Marigny No. 2 – 1,553 burials (1,553 Enemy)

Le Chêne-Guérin – 1,636 burials (1,122 American + 514 Enemy)

Gorron No. 1 – 665 burials (662 American + 3 Allied)

Gorron No. 2 – 654 burials (654 Enemy)

On September 16, 1944, Third Platoon was on the move again, and this time the entire Company was located in the same region. The bivouac was in the heart of a pine forest and nights were cold and damp. Operations consisted mostly of disinterments with Headquarters, 612th QM GR Co, arriving on September 25 to help along with their inspections, restrictions, and orders. Those men that succeeded in visiting and sightseeing Paris returned with tales that things got so expensive that they couldn’t afford them, though some of the more fortunate were able to buy some of the famous perfumes and other souvenirs. Soon all these items became too scarce and highly priced for the average GI.

Following new instructions, the last elements of the 612th QM GR Co finally left France October 11, 1944 for Belgium.

Belgium:

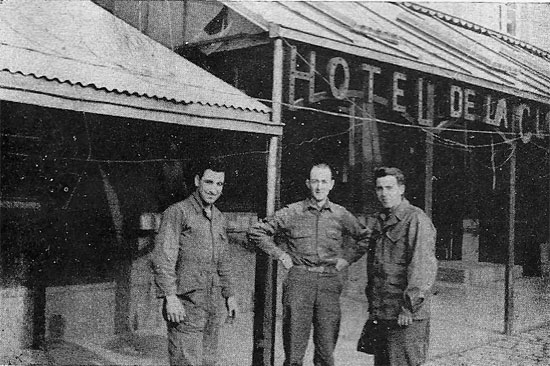

Fosses-la-Ville, Belgium, Enlisted personnel at ease in front of the château where the Fourth Platoon was billeted.

From L to R: Ned C. Titus, Charles R. Schlossberg, Leo Stoll, Jacob J. Zinkevcz, Kenneth L. Hancock, Everett H. Freese, and Clarence Ruiter.

Fourth Platoon moved into Fosses-la-Ville (opened 8 Sep 44), Belgium, immediately behind the liberating Armies, finding the local people very hospitable. They took over a barn for living quarters nearby Namur. On October 8, 1944, First Platoon joined them setting up in the adjoining field in wooden shacks and pup tents. The following day an abandoned château was located, and they all moved in on the second floor. The owner lived on the first floor. Headquarters arrived together with Second Platoon and moved into a School building in the village of Aisemont. As they were the first Americans in town, they received a hearty welcome; within a week anyone interested could easily get an invitation to dinner with a local family and spend an enjoyable evening trying to make the little books on French work. The village fathers got together and put on a first dance since the German occupation.

Operations at Fosses-la-Ville consisted mainly of beautification, burials and getting the burial records up-to-date. There were crosses to be aligned and plot corners to be set in cement blocks. Stringing guide wires were used and available trucks were sent to the airbase at Florennes (Fighter/Bomber Airbase A-78 –ed), where the men alternatively watched the planes take off and land, while shoveling gravel for the cemetery. By Thanksgiving, given the poor weather, trucks couldn’t go into the cemetery as the mud was knee-deep, and even four-wheel drive didn’t help.

Second Platoon was directed to Overrepen, where they tried to get some beautification done on the cemetery. Local people were somewhat hostile and buzz-bombs came over on a fifteen minute schedule, which was very disconcerting. Disinterment was the main source of employment during fall in Belgium. Average crews numbered 5 EM. Usually, the isolated grave could be located and the body removed by noon, and the most unpleasant part of the day was finished. Aside from the half hour unpleasant work, the chance for a day out in the country, and the satisfaction of knowing that another soldier would be identified and given a proper burial made the trips quite popular.

Men enjoyed some recreation at the indoor swimming pool at Jemeppe-sur-Sambre (property of Solvay, which granted permission to use the facilities). The pool was very modern, and there was a bar where refreshments were served. Harvey W. Westfall got the projector in the town theater operating and made a daily trip for the latest movies from Special Services for the Platoon. His shows were well attended by both the men and the civilians.

In November 1944, in the hope of getting the entire 612th together under one roof, all Platoons (except Third Platoon) moved from Fosses-la-Ville to Mettet, some six miles away, on the first snowy days of winter. Third Platoon joined the other troops on November 15, 1944. The new home were offices of a manufacturing druggist and proved ideal, having plenty of little rooms, and by mixing the occupants among the Platoons, Company friendship was once more re-gained. The main office was converted into a dining and day room by addition of benches, tables, and a radio. Frontline progress was checked daily on a large map. A little house nearby was taken over for the supply room and its stove was the warm spot in winter. The basement housed a carpenter’s shop which helped turning out cabinets, foot lockers, signs, and almost anything in wood. An indoor garage helped to keep the trucks operating during winter weather. The formal gardens in the back were converted into a parking lot by adding a few loads of gravel.

The rain and mud increased proportionally with the advancing season, and by December 1, 1944, it was practically impossible to get off a hard surface road without becoming stuck or finding floods with roads and bridges washed out.

On December 4, 1944, Fourth Platoon left the mud-bound cemetery at Fosses-la-Ville for Ménil-la-Tour, France, with hopes of getting away from washing vehicles daily, shoes every time they entered into the building, and wading around cemetery grounds that were practically flooded.

Status of American Cemeteries in Belgium – December 15, 1944

Henri-Chapelle No. 1 – 6,057 burials (5,972 American + 85 Allied)

Henri-Chapelle No. 2 – 2,742 burials (2,742 Enemy)

Fosses-la-Ville No. 1 – 1,323 burials (1,301 American + 22 Allied)

Fosses-la-Ville No. 2 – 851 burials (851 Enemy)

Overrepen – 169 burials (169 Enemy)

The other two cemeteries at Andilly and Limey (opened 6 Nov 44), in France, left the impression that the entire world was about to be washed away. Roads to the cemeteries were impassible and all the open graves looked like wells. Shoveling the mud was impossible, and later when it got really cold and the ground froze, a pick would bounce off the piles of dirt and earth as if they were stone. Third Platoon’s billet was a château in Ménil-la-Tour with an adjoining barn and servants’ quarters. The barn became an office and sleeping quarters were in the château, where one room was converted into a kitchen and mess room.

Antwerp, Belgium. Members of First Platoon during their mission in the city.

From L to R: Jacob J. Zinkevcz, Charles R. Schlossberg, Leo Stoll, Peter J. Schmitt, William R. Virchow, William Huggins, Lt. Gerald H. Myers, Cleston Climer, and Kenneth L. Hancock.

Lt. General Benjamin Lear (Deputy CG, ETOUSA –ed) called Third Platoon to start sweating out the “Repple-Depples” and re-assignment leaving it with some of their best men to operate the two cemeteries and perform the necessary guards, KP, and Room Orderly duties. Back at Mettet, Belgium, Headquarters, First, Second and Fourth Platoons were catching inspections on almost a daily basis by Majors and Colonels, who would stop for an unannounced inspection tour around lunch time. The men were now spending more time washing off their shoes than working in the cemetery. Winter had come to the ETO, something the Army had apparently not counted upon. General “Mud” became an enemy to the men’s feet and to the vehicles; muddy feet became wet feet, and wet feed became receptive to trenchfoot. From the inside looking out, winter in Belgium was indeed a beautiful sight. For the cameras there were pictures aplenty of snow-bound and covered country scenes and vapor trails left by the bomber formations. Clerks must have been snow lovers for sure. The knee-deep mud in the cemeteries got a treacherous crust on it and later froze into solid rock. Overshoes weren’t authorized until practically too late (there were too few of them anyway). Overcoats that should have been turned in to storage in England saved a lot of cold moments for those who had kept them. Cabins built around the driver and co-driver’s seat prevented chill to enter, and the engine heat made driving more comfortable. The road from Mettet to Fosses-la-Ville was a sheet of ice all winter, with many vehicles ending into the ditches.

On December 19, 1944, First Platoon augmented by a Section of Second Platoon (of 4 EM), commanded by Harvey W. Westfall left for a mysterious assignment in Antwerp, Belgium (this followed the impact of a V-2 rocket fired from Hellendoorn, Holland, against Antwerp, Belgium – it fell in downtown Antwerp at 1515 hours, December 16, 1944, destroying Cinema “Rex”, Keyserlei and 11 other houses, causing 567 dead and 291 wounded, among which 296 and 194 US, Canadian and British military personnel – this was the highest death toll caused by a single V-2 rocket attack in Europe –ed). The rain stopped around Charleroi, but the fog got progressively worse, with buzz-bombs coming down the road to Charleroi. After reaching Brussels, a brief rest was called at the American Red Cross Club in Brussels. Three hours were spent in Antwerp trying to locate Lieutenant Ellis V. Clack and Enlisted Man John Brandt, who had preceded the group by a day to check out the situation and locate billets. The search was unfruitful, so the men unrolled their bedrolls on a cement floor in some Belgian Barracks outside town. The following morning a billet in the form of an abandoned Domestic Science School was located by Lieutenant Gerald H. Myers and the group moved. The Belgian Barracks were hit by a buzz-bomb that same afternoon. The augmented Platoon’s mission was to supervise the clearing of a bombed theater downtown Antwerp, and take the bodies of the GIs back to the cemetery at Fosses-la-Ville in the two trucks. Two men were posted on the scene 24 hours a day, while two others tried to sleep and maintain a guard at the billet after work. There was little to do at the scene of the bombing, except collect and remove any body remains, and gaze at the fog, trying to convince oneself that the next buzzer wouldn’t blow in one’s face! Thinking about buzz-bombs, the ones that really made the lines under the men’s eyes were the heavy rockets, or V-2s. They would sneak in completely unannounced and blow everything to smithereens.

While in Antwerp, there was little or nothing in the line of recreation as orders had closed all shows and public meetings of 25 or more people. There were only a few little bars open where one could buy a beer or cognac and listen to some records from America. After a week in and out of town nobody didn’t get up to look at the buzzers anymore. Christmas was spent in Antwerp and became one of the highlights of the First Platoon’s stay in the town. Everyone enjoyed a turkey dinner with some good ‘liberated’ wine. Most men were still asleep the following morning when a buzz-bomb was intercepted by the local church steeple. They were awakened by chunks of plaster hitting them and the tinkling of flying glass. A quick survey showed the barracks minus many windows, doors, walls, and a church a half block away. On New Year’s Eve, December 31, 1944, the group packed and got into the trucks to return to Mettet. Mettet wasn’t much better, the Company was still there, but the Bulge had advanced to within fifteen miles, and it looked like this was no place for a Graves Registration Company armed with .30 caliber carbines and shovels. Plans had been made for any coming enemy attack if it should take place. The trucks were always gassed and headed out towards the gate. The men slept in their clothes and shoes with weapons loaded and gas masks handy. The guard was trebled with orders to “shoot first, then interrogate!” All equipment was marked to separate whatever must be abandoned. By Christmas, Infantry Replacements had been calling men from the 612th to such an extent that transfers had to be called for to bring the Company up to strength during the Battle of the Bulge. MPs on the road were stopping everybody on the road asking special questions relating to life in the Zone of Interior.

Fourth Platoon lost 7 EM to the Infantry in January 1945. On January 21, 1945, three Enlisted Men; Leo Fixler, Clarence Ruiter, and William R. Virchow were sent on DS to take charge of two cemeteries, one at Molenhoek (opened 20 Sep 44), and the other at Son (opened 19 Sep 44), Holland. They rejoined the Company after four or five months. Back in Mettet, Belgium, the 612th received orders to open a cemetery near Liège to take care of the Bulge casualties. On January 20, 1945, a site was selected near Neuville-en-Condroz (opened 8 Feb 45), and a billet near Rotheux to house Second Platoon. Surveying was done in three days, and inside a week, the laborers were finishing the first row of graves when during the night a buzz-bomb landed in the center of the new cemetery making a hole some 30 feet in diameter, revealing a network of broken water pipes (the water supply of the town). A new site was thus located in the same vicinity and the process repeated. The German part of the cemetery had to be cleared of ammo and mines by Bomb Disposal squads. After work, passes were obtained for Liège to attend some of the shows in the evenings.

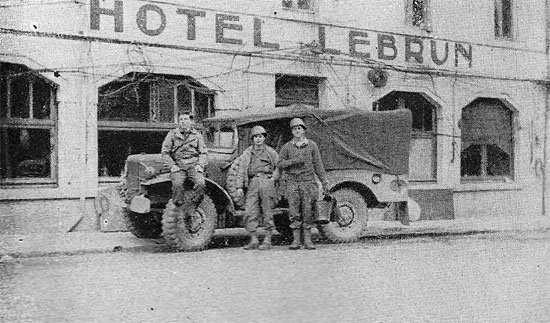

Bastogne, Belgium. Some members of First Platoon in front of their 3/4-ton Weapon Carrier enjoy a short break for a picture.

From L to R: Thomas B. Piper, Joe J. Rodewald, and Frank G. Lowenstein.

On February 2, 1945, First Platoon left Mettet for Grand-Failly (opened 24 Dec 44), France, to operate and work at a new cemetery. Beautification operations were started when Third Platoon relieved the First which returned to Headquarters at Mettet, Belgium. Lieutenant William H. Staub requisitioned 300 German PWs, and had them build their own enclosure near the cemetery. A QM Service Company was called in to do the guarding. The roads had to be widened, graveled, and paths built around the plots; the graves were leveled and the crosses aligned. A captured German baker came in every evening for five hours, baking cakes, cookies, and fancy pastries for both the men and the guards. Other prisoners scrubbed, cleaned, and dusted the building, washed dishes, did the laundry, and other odd jobs. More EM left for the Replacement Depots in February.

Joseph Bryant, John V. Burman, Albert Leonetti, Willie C. Nall, Alphonso Renteria, Richard Ruscigno, and Joseph W. Santora, were the first of the 612th QM GR Co to get to Germany. They were sent to Niederbreisig, Germany, to take care of the Graves Registration work for the 56th Quartermaster Base Depot.

First Platoon left Headquarters at Mettet, for Marche, Belgium. Operations consisted of following Engineer squads with mine detectors for miles through the Ardennes Forest, recovering and bringing out bodies. It was a tricky job, and men had to be aware of the many booby traps left behind. Meanwhile, Fourth Platoon proceeded to Neuville-en-Condroz to join the Second. Buzz-bombs were still a plague as they would fall short or be intercepted. The nearby village of Rotheux suffered 35 hits during the period. After a month, Fourth Platoon relieved First Platoon in Marche, Belgium. Collecting operations continued with the bodies being taken to Neuville-en-Condroz for Second Platoon to take care of. Only two people were left at Fosses-la-Ville to raise and lower the flag.

From Marche, First Platoon moved to Bastogne and shared a building with some Signal Corps personnel pertaining to the 28th Infantry Division. At the Foy cemetery (opened 4 Feb 45), approximately eight miles north of Bastogne, Thomas B. Piper, Joe J. Rodewald, and Jacob J. Zinkevcz, built a wooden shack and moved in to act as guards. Operations consisted mainly of recovering battlefield casualties from the woods and burying them at the cemetery. The forest was thick with abandoned weapons and ammunition.

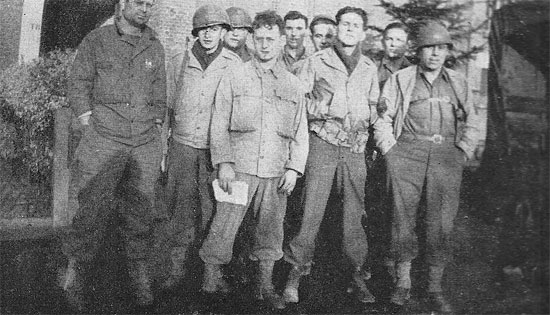

612th QM GR Co personnel in front of one of the local hotels in Marche, Belgium.

From L to R: James D. Brusuelas, Robert A. Fullerton, and William Huggins.

On March 23, 1945, Fourth Platoon left Marche and moved onto a new site, the cemetery at Henri-Chapelle (opened 25 Sep 44). Their billet was a Monastery where the Nuns proved more than hospitable, doing such favors as laundry and mending clothes.

Luxembourg:

On April 2,1945, First Platoon rolled on for the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg, where Lieutenant Ellis V. Clack found them billets in a School building at Hamm. Joseph Okarma, Joe J. Rodewald, and Jacob J. Zinkevcz lived in the American cemetery, and Cleston Climer, Thomas B. Piper, at the German part. Hugh B. Mooney, and Fred J. Tyson, later joined them. Charles H. Block busied himself with the carpentry work. Operations at the cemetery consisted mostly of disinterments. Every Saturday night, there would be an all-night session preparing the forms to meet the deadline early Sunday morning. Operations at Hamm cemetery (opened 29 Dec 44) were taken over by Detachment B, 3045th QM GR Co, who relieved the last elements of the 612th on April 29, 1945.

Hamm, Luxembourg. First Platoon members Joseph Okarma, Reid W. Martin, and Jacob J. Zinkevcz look over the cemetery.

Germany:

Robert A. Newbold, Thomas B. Piper, Peter J. Schmitt, and Leonard H. Stein, set off to handle Graves Registration work for the 53d QM Base Depot at Ingelheim, Germany.

On April 23, 1945, Fourth Platoon left Henri-Chapelle, Belgium for Ittenbach, Germany, where they set up in a large home. Operations consisted of battlefield recoveries with a few disinterments.

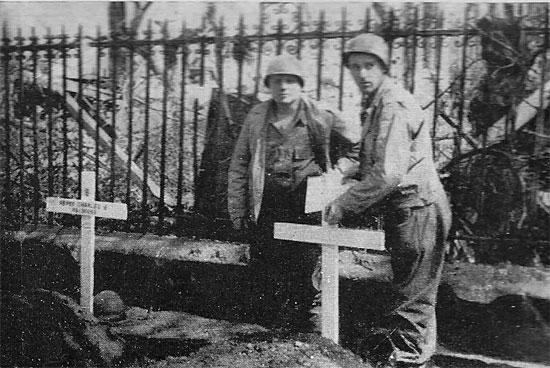

Disinterments, Enlisted Men Reid W. Martin and William Jackson check the reports against some isolated burials before bringing the bodies back to an American cemetery…

On April 30, 1945, First Platoon moved into two neighboring duplex houses in Butzbach, Germany. Two men were detached to the cemetery, acting as guards, and raising and lowering the flag, while moving into a pyramidal tent. On May 1, 1945, Second and Fourth Platoons moved to Ittenbach joining the First on site. Beautification efforts were emphasized with the men painting and stenciling names on the wooden markers, installing gravel paths, and landscaping with shrubs requisitioned from a local nursery. Activities were then shifted into second gear in anticipation of the coming of “Memorial Day”.

Another Section left under command of Captain Gates to lay out German cemeteries near Rheinberg, Budrich, and Wickrathsburg to handle the deaths in the PW Enclosures.

V-E Day, May 8, 1945, found Headquarters of the 612th, parts of the Second and Fourth Platoons enjoying life at Ittenbach, Germany. Third Platoon on their way to Lintfort, the First still at Butzbach, and William Jackson’s Section counting their points in Bingen. Third Platoon was brought back from Grand-Failly, France, on May 9, 1945, to join the First in Butzbach, where they spent the night. First Platoon moved from Butzbach to Bingen to augment the Section stationed there in order to help with the paperwork at the two cemeteries at Heidesheim and Bad Kreuznach, Germany. The latter also held a PW cemetery. German PWs did all the burying, some of the paperwork, cooking meals, and handling laundry.

Status of American Cemeteries in Germany – May 11, 1945

Ittenbach No. 1 – 1,544 burials (1,505 American + 39 Allied)

Ittenbach No. 2 – 962 burials (962 Enemy)

Breuna No. 1 – 1,674 burials (1,520 American + 154 Allied)

Breuna No. 2 – 378 burials (378 Enemy)

Eisenach No. 1 – 375 burials (335 American + 40 Allied)

Eisenach No. 2 – 142 burials (142 Enemy)

About July 1, 1945, Third Platoon relinquished its hold on Lintfort and returned to Ittenbach; First Platoon followed July 11, bringing the entire Company together for the first time since Thanksgiving. Life was good, as there were no inspections, no reveille, no retreat, and even breakfast was optional.

Horseshoe and ping pong tournaments were organized, with picnics with swimming at the pool beside the River Rhine, baseball games, and a keg of beer were a Sunday function. Boats were chartered for evening trips up the Rhine past historic places and the Remagen bridge. As the cemetery was finally closed, bodies were now taken to Margraten (opened 28 Sep 44), Holland, with an overnight stop at Liège, Belgium. Passes and furloughs were obtained to visit Paris, Liège, and other places.

Heidesheim, Germany. Leonard H. Stein, Charles H. Block, William Jackson, Peter J. Schmitt after having enjoyed one of Stein’s meals.

The End:

As far as the authors know, the 612th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company ceased operations in Germany on August 10, 1946, following which it was transferred for a short while in Vienna, Austria, before returning to Karlsruhe, Germany, where it remained until February 19, 1948. It was subsequently inactivated by Headquarters, European Command, March 20, 1948 and returned to the continental United States…

Campaign Credits – 612th QM Graves Registration Company

Normandy

Northern France

Rhineland

Ardennes-Alsace

Central Europe

Roster: (incomplete)

Officers

Thomas A. Rowntree (Texas) Captain, Commanding Officer

Ellis V. Clack (Mississippi) First Lieutenant, Executive Officer

Robert E. Barry (New York)

Gerald H. Myers (California)

Richard C. Steegmuller (New York)

William H. Staub (Maryland)

Bingen, Germany. Some men are sipping Champagne, celebrating V-E Day.

From L to R: Frank G. Lowenstein, Ned C. Titus (standing), William Huggins, Robert A. Newbold, and Fernon E. Harrison.

Enlisted Men:

| John R. Adams (Massachusetts) | Reid Grayson (Montana) | George H. Pens (Colorado) |

| Winton Alexander (Alabama) | Winston Greenwell (Utah) | Walter E. Perry (Oregon) |

| Alvin C. Anderson (Iowa) | John P. Halavonich (West Virginia) | Thomas B. Piper (Michigan) |

| Alex A. Armenta (Mexico) | Kenneth L. Hancock (Nebraska) | John Pivaroff (California) |

| Lester Barber (New York) | Arvin Hanson (Minnesota) | Stanley J. Plichta (Michigan) |

| Robert L. Barrett (Indiana) | Earl Harr (South Dakota) | J. P. Posey (Texas) |

| John W. Baxley (Georgia) | Howard G. Harris (New York) | William C. Price (California) |

| Joseph H. Beauchene (Washington) | Fernon R. Harrison (Texas) | Leslie Proctor (Arkansas) |

| Walter Benet (Maryland) | Frank W. Hart (Oregon) | Ted Pruitt (California) |

| Russell F. Bertschinger (Michigan) | Jonas C. Hartsell (North Carolina) | George B. Quinn (California) |

| Edwin W. Bland (Ohio) | Forrest W. Hayne Jr. (Ohio) | William P. Raner (California) |

| Charles H. Block (California) | Vicente G. Herrera (Arizona) | Martin W. Reid (Missouri) |

| Ray Boots (Missouri) | John F. Higgins (Illinois) | Leon Rejman (Iowa) |

| John Brandt (Indiana) | Wallace Hildreth (California) | Paul J. Roberson (Virginia) |

| Walter L. Briggs (California) | Clarence B. Hodge (North Dakota) | George J. Roberts (Ohio) |

| Everett R. Bristow (California) | William L. Hodge (Tennessee) | Kenneth L. Robbinson (Iowa) |

| James D. Brusuelas (New Mexico) | John Honstein (Oregon) | Meade M. Robinson (Florida) |

| Joseph Bryant (North Carolina) | William Huggins (Oregon) | Alphonso Renteria (California) |

| John V. Burman (Minnesota) | William Jackson (Oregon) | Victor J. Richter (Texas) |

| John E. Burton (Texas) | Harry Jeffries (New Jersey) | Joe J. Rodewald (Missouri) |

| Richard Burwick (California) | Kay Jew (California) | Duane Rogers (Wisconsin) |

| Pablo Cabrera (Texas) | Johnnie F. Johnson (Kentucky) | Clarence Ruiter (Illinois) |

| James R. Calloway (Idaho) | Herman C. Kammauff (Maryland) | Richard Ruscigno (California) |

| Cohen Campbell (South Carolina) | John E. Keane (Pennsylvania) | Joe S. Saddoris (Texas) |

| Edward Campbell (Kentucky) | John Knight (Montana) | Joseph W. Santora (Massachusetts) |

| Robert E. Carr (California) | Paul E. Kumigoski (North Carolina) | Morris P. Savoy (Ohio) |

| Steve Cikel (Wisconsin) | Joseph Labrecque (New York) | Philip Schaff (California) |

| Clarence Clemens (Minnesota) | Albert Leonetti (Ohio) | Charles R. Schlossberg (West Virginia) |

| Cleston Climer (Washington) | Cedell Lewis (Mississippi) | Peter J. Schmitt (Minnesota) |

| Ralf E. Conrad (California) | William C. Libby (Illinois) | Richard G. Sequin (California) |

| Paul K. Cook (Illinois) | William L. Lindt (Idaho) | Marion Simpson (Texas) |

| Leslie Courter (Ohio) | Joseph Longman (Minnesota) | Binom H. Smith (Arkansas) |

| Walter Craker (Texas) | Louis P. Lopresto (Mississippi) | Americo E. Solazzi (Massachusetts) |

| Daniel L. Curatola (Pennsylvania) | Keong Lowe (California) | Douglas E. Spinks (Texas) |

| Joyce E. Curtin (California) | Frank G. Lowenstein (New Jersey) | Edward J. Spurlock ((West Virginia) |

| Riley Daugherty (Nevada) | Irving J. Malbin (New York) | Hubert W. Starns (Missouri) |

| Henry DeBrown (Illinois) | Maurice Markowitz (New York) | Leonard H. Stein (Oklahoma) |

| John DeNardo (Illinois) | Edward A. Massey (Florida) | Jennings E. Stiltner (Virginia) |

| John D. Donaldson (California) | Setsuo Matsuo (Hawaii) | Leo Stoll (Texas) |

| Thomas J. Dowling (California) | Joseph P. Mattera (California) | Robert R. Sunderland (California) |

| Edward Driscoll (Massachusetts) | Setsuo Matsuo (Hawaii) | James V. Surber (California) |

| Joseph Dudiak (Ohio) | Joseph E. McCarthy (Canada) | Ned C. Titus (Indiana) |

| Jerry Dwyer (California) | Jack T. McClain (South Carolina) | Howard Toevs (Idaho) |

| Alvin Engle (Kansas) | Joseph C. Meagher (Oregon) | Roberto E. Torres (California) |

| George Esgate (Oregon) | Adrien E. Melancon (New Hampshire) | Harvey T. Trippel (Illinois) |

| Robert Falls Down (Montana) | Casimir Miedzwiecki (Pennsylvania) | Wilmer Tuttle (Arkansas) |

| William A. Fisher (California) | Delbert Mihulka (Nebraska) | Donald W. Tyler (Washington) |

| Leo Fixler (Missouri) | Steve Mikich (California) | Fred J. Tyson (California) |

| Charles I. Flory (Pennsylvania) | Winfred E. Mock (Montana) | Foster B. Vary (Florida) |

| Fred Frazier (North Carolina) | John A. Molinari (California) | William R. Virchow (Massachusetts) |

| Joseph Frediani (California) | Henry Moody (Alabama) | Warren Walker (Indiana) |

| Everett H. Freese (Illinois) | Hugh B. Mooney (Ohio) | Harry A. Wallinder (Illinois) |

| Robert A. Fullerton (Oregon) | Frank A. Myers (Iowa) | Theodore E. Ward (California) |

| Santiago T. Galaz (New Mexico) | Willie C. Nall (North Carolina) | Edward R. Webb (Iowa) |

| Fred S. Garcia (California) | Harry G. Natchke (South Dakota) | Harvey W. Westfall (California) |

| George S. Garcia (Arizona) | Joe A. Neal (Tennessee) | Melvin J. Wignall (Nevada) |

| Rinaldo Garofoli (Pennsylvania) | Robert A. Newbold (New York) | Charles O. Whitaker (California) |

| Chester A. Garthwaite (Wisconsin) | Lavern R. Nieman (Iowa) | James D. White (West Virginia) |

| José F. Garza (Texas) | Thomas C. O’Donnell (Michigan) | Ross W. Wilkinson (Idaho) |

| Clifford L. Gauvain (Missouri) | Joseph Okarma (Pennsylvania) | Roger D. Williams (Washington) |

| Walter J. Gehringer (Pennsylvania) | Casimiro Ortega (Texas) | Russell A. Williams ((Virginia) |

| Vincent Goes Ahead (Montana) | Reuben C. Ortiz (California) | Theodore Woloszyn (Illinois) |

| Louis Good Luck (Montana) | Phillip E. Parasko (New York) | Alvin R. Wright (California) |

| Preston N. Grandel (Virginia) | William C. Parker (Pennsylvania) | Rocco F. Zaino (New York) |

| Oleton E. Gray (North Carolina) | Stanford H. Pearlman (Illinois) | Jacob J. Zinkevcz (Wisconsin) |

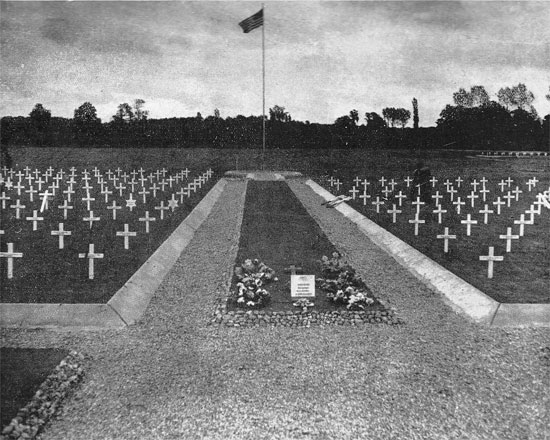

General view of St. Corneille American Military Cemetery, situated near Le Mans, France.

The MRC Staff wish to express their sincere thanks to Bob Moolenbeek for kindly providing them with copies of the book “C’est la Guerre” (published in Bonn, Germany) covering the 1943-1945 operations of the 612th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company. Without his kind help, editing the above Unit History would have been impossible.