77th Evacuation Hospital Unit History

“Medicine under Canvas” – A War Journal of the 77th Evacuation Hospital. 2008 Reprint by The University of Kansas School of Medicine of the original Journal published by The Sosland Press, Inc., Kansas City, Missouri, in 1949.

Introduction:

In the summer of 1940, the US Army Surgeon General proposed to the Dean of the Medical School, University of Kansas, the organization of a professional team consisting of Doctors and Nurses for setup of an affiliated Evacuation Hospital unit. The staff and faculty of the Medical Staff accepted the proposal and selected Dr. James B. Weaver to head the surgical section and Dr. Edward H. Hashinger to head the medical section respectively, with the latter serving as the unit Director.

The 77th Evacuation Hospital was officially activated 17 May 1942 at Ft. Leonard Wood, Rolla, Missouri, and was to see action in North Africa, Sicily, and Europe during World War 2. Enlisted personnel were supplied by the 42d Evacuation Hospital (activated 1 June 1941). The new unit embarked for England 5 August 1942 after thorough training in the Zone of Interior.

Organization:

The 77th Evac Hosp with a bed capacity of 750 constituted a channel through which passed many casualties from the combat zone on their way to the Army Hospitals of the Communications Zone. The early T/O 8-580, dated 2 July 1942, authorized a total strength of 318 Enlisted Men, 52 Nurses, 1 Hospital Dietitian, and 47 Medical Corps Officers. Quite a number of Enlisted personnel were assigned to administrative services, such as Headquarters, Registrar & Detachment of Patients, Personnel Section, Receiving Section, Evacuation Section, Mess Section, and Supply & Utilities Section. Others served with the professional services, including Medical Service, Surgical Service, Laboratory Service, Roentgenological Service, and the Dental Service.

The purpose of the organization was to:

- To provide facilities for major medical and surgical procedures in treatment of casualties as near to the front as practicable

- To provide definitive treatment to patients as early as practicable

- To relieve combat troops of the burden of prolonged care for casualties

- To provide facilities for concentration of evacuees so that mass evacuation by rail, motor, aircraft, or water transport could be undertaken quickly and economically

- To prepare serious or critical cases for further evacuation

- To remove from the chain of evacuation those casualties fit for duty

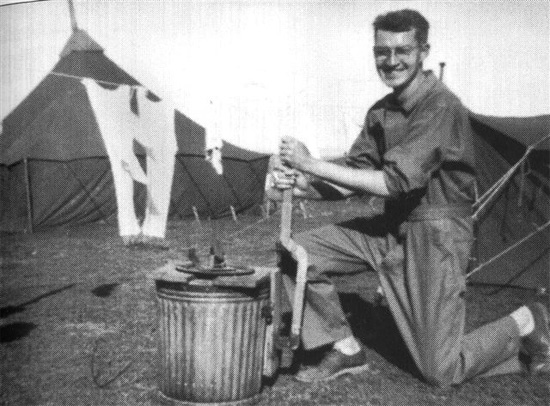

Enlisted personnel during training at Ft. Leonard Wood, Rolla, Missouri, some of the men take a break. Picture taken June-July 1942.

Properly trained, an Evacuation Hospital would be able to establish the installation in 4 to 6 hours and dismantle and move it from 8 to 10 hours after being cleared of patients. Dismantling and moving would normally proceed in the following sequence: basic unit (less messes and headquarters), secondary wards, evacuation wards, administrative offices, headquarters, personnel quarters, messes, sanitary installations. It was recommended to move by rail (such movements required 2/3 of a train) or if impossible by motor convoy (184 truck tons required for equipment only).

Activation & Training:

When the roll of Officers was completed, a first attempt at preliminary training was made by means of medical lectures, followed by attending more lectures and courses provided at Ft. Leavenworth, Leavenworth, Kansas (Command & General Staff School –ed). Meanwhile a group of 144 EM was sent to Ft. Leonard Wood, Rolla, Missouri (Engineer Replacement Training Center and Division Camp –ed), in July of 1941 to activate the 42d Evac Hosp where they followed a training program with Captain Richard S. Fraser as Commanding Officer. In addition to their current unit duties, the men were assigned to the different departments of the Station Hospital to practice their skills. Some of them were further sent on Detached Service to Army Specialist Schools during the remainder of 1941 and early 1942.

Early spring of 1942 brought rumors of more active duty and on 10 May 1942 the process of activation of the 77th Evacuation Hospital was initiated by the transfer of Captain Richard S. Fraser and Captain Martin F. Anderson, and 106 Enlisted Men from the 42d Evacuation Hospital. Officers and Nurses to be assigned to the newborn Hospital left the Medical School at the University of Kansas and prepared to join the 77th EH. On 17 May 1942, a group of 35 Officers reported at Ft. Leonard Wood. After arrival and initiation of the unit training program, Lt. Colonel Edward H. Hashinger assumed command until arrival of the official CO, Colonel Burgh S. Burnet on 4 June 1942. On 15 June 1942, the main body of ANC personnel joined the new unit headed by First Lieutenant Bessie Walker, who was appointed Principal Chief Nurse.

Several contingents of EM arrived from Cp. Grant, Rockford, Illinois (Medical Replacement Training Center –ed), and Cp. Joseph T. Robinson, Little Rock, Arkansas (Infantry Replacement Training Center –ed), increasing the total of Enlisted personnel to 284. A team of Second United States Army Inspectors visited the unit and although the organizational equipment was far from complete, they were satisfied by the unit’s fitness for field duty. Anyway, the 77th was alerted at 2400 hours, 24 July 1942, and started preparations for a move. Last minute arrivals included 1 Officer and 6 EM, all of whom arrived within the last forty-eight hours prior to the unit’s departure of Ft. Leonard Wood.

Personnel of the 77th Evacuation Hospital at work to set up a ‘model’ hospital’…

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

Prior to the departure of the main body, 3 advance parties left Ft. Leonard Wood. First Lieutenant Robert L. Newman was sent to the New York P/E to supervise assembly and loading of the organizational equipment. A second detail under First Lieutenant Glenn C. Franklin with 4 Enlisted Men went to the Indiantown Gap Staging Area, Pennsylvania (Military Reservation and Training Center –ed), to make arrangements for quarters and rations for the main body. Another small group under Sergeant Virgil L. Mayes, assisted by 4 EM loaded the unit vehicles onto railcars at the Ft. Leonard Wood railhead and traveled with them to the Staten Island terminal.

On the evening of 30 July, all baggage and personal equipment was loaded and the following morning a truck convoy arrived to take the group to the train. Around 0900, the train departed after having been loaded with little confusion. As it got under way, the personnel roster was again checked, and it found everyone duly accounted for. The train trip finally took an end after three long days and trucks drove the personnel to the camp and staging area where they were assigned living quarters upon arrival. After messing, the staging began. Officers made last minute purchases of woolen clothing at the PX, Nurses were issued clothing to complete their blue uniform, and Enlisted Men turned in their cotton khaki uniforms for wool ODs. More EM from Camps Barkeley, Abilene, Texas (Medical Replacement Training Center and Armored Division Camp –ed) and Grant brought the total to the prescribed strength of 318.

New M-1 steel helmets and liners were issued, personal baggage was stenciled with the shipment number, 9190-0 (the unit’s coded designation) and the entire outfit received typhus immunization shots. Photographs were taken for the ID documents. During the days and nights passed at the staging area no communication with the outside world was allowed. The organization’s official address became APO 1289, c/o Postmaster, New York, N.Y. After 4 days of concentrated preparation at “The Gap”, 6-wheeled 2 ½-ton trucks were boarded for another run to the railway station and on to New Jersey. Arriving at dark, the unit waited for a ferry on the Jersey side of the Hudson River that would bring them to one of the oceangoing vessels waiting in their berths. At the pier, Enlisted Men were waiting in line for a roster check, while the Nurses who had arrived earlier were rummaging through crates of clothing and shoes. 9 Nurses were already on board having been assigned to the 77th from Ft. Eustis, Lee Hall, Virginia (Antiaircraft Artillery Replacement Training Center –ed) and Camp Pickett, Blackstone, Virginia (Division Camp –ed) and were already settled in their stateroom quarters.

Stations in Zone of Interior – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri – 17 May 1942 > 31 July 1942

Indiantown Gap Military Reservation, Pennsylvania – 1 August 1942 > 5 August 1942

Atlantic Crossing:

The ship to board was the British troopship “Orcades” (built in 1937, former Orient Steam Navigation Co. Ltd. Ocean liner converted to troopship, and sunk by U-172 on her way from Capetown, South Africa, to the United Kingdom, 10 October 1942 –ed). Among the more than 5,000 troops aboard were a Medical Regiment, several Field Artillery Battalions, an Armored unit, an Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, the 77th Evacuation Hospital, and a few smaller units. During the voyage a blackout system was in effect necessitating the closing of the portholes for 15 hours out of 24. Enlisted Men slept everywhere in hammocks, in tiers, installed in crowded compartments in the hold. Officers received the best accommodations. Sanitation presented some problems and it was always necessary to stand in line. Washing and shaving facilities were extremely crowded and one had to queue for a seawater shower. It was difficult to adjust to the British food and moreover messing facilities were very poor so that following distribution, food had to be carried back to the men’s compartments in mess kits.

After leaving on 5 August 1942, the convoy steamed into Halifax harbor on 7 August, and after having been joined by several other ships, left the following morning. During the first days, Navy blimps and Catalina flying boats patroled the waters but as their range was exceeded by the convoy’s progress, they gradually disappeared. The ship’s sickbay was taken over by 77th personnel who were assigned to take care of the usual medical cases. A few days out of Halifax, several ships bound for Iceland left the convoy. The weather then took a turn for the worse and faces turned greener – each day, fewer people appeared for meals. The convoy passed through particularly dangerous waters during the last part of the voyage and all personnel were therefore ordered to sleep in their clothing. As the convoy started entering the Irish Sea, the weather calmed down, and the first sight of the hills of Ireland appeared through the mist. British Spitfires flew over the ships which now began their own journey; some put in at Glasgow, and others continued toward Liverpool. The evening of 17 August 1942, the “Orcades” and two other troopships were being tied up at Prince’s Landing Stage, Liverpool. By 2200 hours all necessary arrangements had been completed and debarkation could begin …

United Kingdom:

After marching to the Liverpool Lime Street Railway Station, British trains took the unit through the Midlands, the outskirts of London, up to Salisbury Plain. The next day the train reached Tidworth in the afternoon, where Officers and Enlisted Men marched about one mile north of town to an open area known as Tidworth Park. The Nurses had been taken by bus to Salisbury where they were billeted in the American Hospital. Meanwhile, a working party, consisting of Captain Max S. Allen and 8 EM had remained at the ship to supervise unloading of the organization’s baggage, including footlockers, bed rolls, barracks bags, field kitchen ranges, boxes of records and crates of office equipment. After five days of hard work, the unloaded equipment had been secured on British boxcars, and started its journey to Tidworth where it arrived one week after the main party.

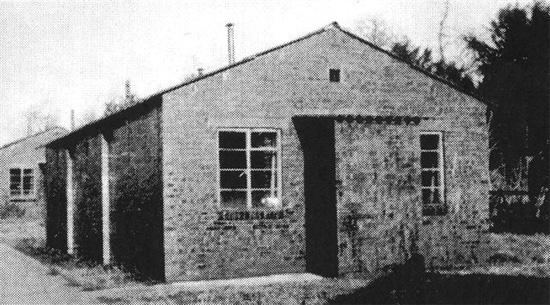

Picture illustrating the type of living quarters used by the Nurses while stationed at Everleigh Manor, England. Picture probably taken in January 1944.

Huge brick barracks, once occupied by the British Army, were taken over by the United States First Infantry Division which had just arrived, having gone through “The Gap” too, about four days ahead of the 77th Evac. Officers and Enlisted Men were now scattered in British tents, issued only two British blankets, and had to undergo poor living conditions, with cool weather, chilled and damp nights, and lots of rainfall, although it was August. The tents leaked, the coal-burning stoves were antiquated, water for washing and shaving was cold, and warm water for showers was warm for only a short period each day. Latrines were of the honey-bucket type and without paper. The situation turned for the worse when more American units arrived, including the 38th Evacuation Hospital (activated 16 April 1942, affiliated to Charlotte Memorial Hospital, Charlotte, North Carolina, embarked for England 5 August 1942 –ed) and the 48th Surgical Hospital (activated 10 February 1941, embarked for England 2 August 1942 –ed). As British personnel operated the kitchens, the food was merely a repeat of the routine on the ship. Finally, the entire mess system was taken over by US personnel, improving the palatability of the daily meals considerably. Getting accustomed to British ways, habits, and customs was not easy. Luckily the food and snacks served at some NAAFI places and pubs furnished some diversion from the standard foodstuffs served in camp. Individual laundry had to be done in helmets and in cold water and dried at night. A dispensary was opened for the entire camp but medical supplies at the time were very meager.

Stations in England – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Tidworth Park, Wiltshire – 18 August 1942 > 3 September 1942

Frenchay Hospital, Gloucestershire – 7 September 1942 > 26 October 1942

Camouflage, blackout, and passive defense regulations brought many new experiences and trenches had to be dug for protection against possible enemy air attacks. Apart from the daily activities, calisthenics, close-order drill, road marches and races were held almost each day. Forty-eight hours passes were issued for visits to London, Bournemouth, and Southampton. ANC personnel meanwhile led quite a pleasant existence at the American Hospital in Salisbury (which occupied a 22-building complex near the city since September 1941, also designated the “Harvard Unit” –ed) quartered in one wing of the hospital complex with other American Nurses and living in comfortable conditions with radio, recreation room, and snack kitchen.

On 4 September 1942, a detail of 75 Officers and a group of Enlisted personnel traveled by train to Frenchay Hospital, near Bristol, to take over a new Hospital Plant that was still under construction. The buildings were cleaned, the necessary British equipment installed, and within a few days the remainder of the Officers and EM, and all the Nurses arrived. This caused quite a boost in morale, and after American rations became available, the situation on the whole was excellent in comparison to Tidworth.

Within a short time the 77th Evacuation Hospital was ready for operations and the first patients were received from US troops in the surrounding area and from the 2d General Hospital (activated 31 January 1942, affiliated to Presbyterian Hospital, New York, N.Y., embarked for England 1 July 1942 –ed) at Oxford. Both Officers and Enlisted Technicians followed medical and surgical technique courses; some went to attend lectures at various Hospitals and Medical Schools in England, and handling of the British equipment (the only one available at the time) was taught. Gradually the organization began to function more smoothly and attendance to local dances, pubs, and theaters increased, leading to many acquaintances and friendships with the citizens of Bristol and the outlying villages in the area. For recreation and sports, a baseball diamond and a football field were laid out with the locals always turning out in force to see these strange American games played. Collecting the Hospital’s necessary items of equipment caused quite a few problems. Approximately 80 to 90% of it had been procured, assembled, and labeled for shipping to England. On arrival in the UK, the equipment had been stored in a Medical Supply Depot where it was to be held until the unit was ready to use it. Unfortunately another Hospital needed the equipment before the 77th did. Only 30% remained for the 77th Evac and securing what was missing proved a formidable task. After attempting to locate the necessary items, close to 90% finally became available, yet some essential items were still missing, and it was now a case of either substituting some parts by makeshift improvisations or try and purchase them on the open market …

During the latter half of October 1942, rumors of a big move buzzed about camp. Meanwhile more supplies poured in, extra winter clothing was issued, and gas-protective ointment distributed. The Nurses received pup tents. Two War Correspondents (New York Times + New York Herald-Tribune) were attached to the organization, and instructions issued to properly crate and mark all the equipment for a possible move overseas. A temporary reorganization was introduced with personnel being divided into A and B groups, each capable of operating as a separate evacuation unit with Surgeons, Nurses, Technicians, and clerical personnel. To add to the individual barrack bags, musettes, and others, C-rations, D-bars, fruit juice, corned beef, cheese, sardines, cigarettes, and chewing gum were issued. On 26 October, personnel from the 2d Evacuation Hospital (activated 22 January 1942, affiliated to St. Luke’s Hospital, New York, N.Y., embarked for England 4 September 1942 –ed) arrived to take over the remaining patients and the plant.

Group A left on the evening of 27 October while group B was scheduled to go on 29 October 1942. Only 2 men were left behind, being ill and in hospital at the time of departure.

North Africa:

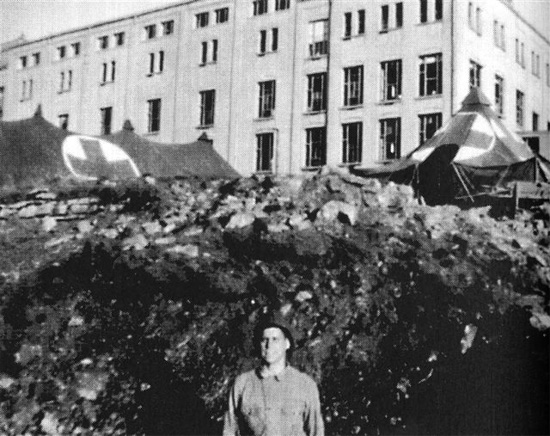

Partial view of 77th Evacuation Hospital personnel at work in the unit’s installation often designated the “Oran Mud Flats”. Some described it as living in a cold hog-wallow, others called the soft red mud the “Oran Ooze”. Picture taken in December 1942-January 1943.

The train ride to Liverpool was uneventful and tiresome, the large part of it occurring during blackout hours. Group A arrived near Prince’s Landing Stage on the afternoon of 29 October and immediately boarded USAT “Uruguay”. The second group reached the dock on the afternoon of 30 October and boarded USAT “Brazil (sister ship of the “Uruguay”). Both ships sailed at 1400, 31 October 1942, and the following morning found them anchored in the Firth of Clyde, near Gourock, Scotland. Former South American passenger ships, each of the ships could accommodate roughly 5,000 troops and offered more comfort in quarters when compared to the British transports. Food was of excellent quality and quantity, although only served twice a day. At 2100 hours, 1 November 1942, the completed convoy sailed out of the harbor heading for the Atlantic, and as the ships’ course turned more southward, warm tradewinds brought their passengers out to the open decks.

Since no official information had yet been given out, the organization still ignored their destination. On 4 November, however, Officers were briefed and a copy of the booklet, “A Guide to North Africa” was given to everyone. The “Brazil” and “Uruguay”, among others, were bound for Oran, Algeria, and maps of the city were soon brought out to show and discuss the location where the 77th Evac Hosp was to operate. British and American Officers (some of whom had lived in or visited North Africa before) gave orientation lectures and briefed the personnel on tropical diseases and the current political situation. Later, Atabrine for the prevention of malaria was distributed together with water purification tablets, dust goggles, and anti-gas eye protection shields. British currency was exchanged for American notes.

On 8 November 1942 the news that North Africa had been invaded by a combined Anglo-American force (Operation “Torch” –ed) came over the radio and was broadcast through the ships via the PA system. The first convoy, part of Center Task Force, included medical personnel from the 400-bed 48th Surgical Hospital and the 750-bed 38th Evacuation Hospital which participated in the D-Day assault.The second convoy (expected to land on D+3) included medical support troops belonging to the 77th Evacuation Hospital and the 51st Medical Battalion. It now moved directly through the Straits of Gibraltar, passing Tangier, Spanish Morocco, continuing into the calm waters of the blue Mediterranean Sea. As the enemy submarine danger became greater, the speed of the convoy increased. There was some relief when half of the convoy peeled off heading for Oran, Algeria. But since the harbor was blocked by sunken ships, it became necessary to put in at Mers-el-Kébir (3 miles west of Oran), where the ships anchored for the night. The date was 11 November 1942.

Upon arrival at the pier, Officers and Enlisted Men on the USAT “Brazil” were ordered to disembark immediately while the Nurses were instructed to remain aboard ship for further orders. They were later picked up by motor launches and taken to Oran to wait for the other Nurses from the “Uruguay”. On 11 November, the day following the surrender of Oran the 38th Evac Hosp moved further inland where heavy fighting was taking place, with the Hôpital Civil being taken over by personnel of the 77th the following day. The units on site were supplemented from 21 November onward by the 9th Evacuation Hospital (activated 24 August 1942, affiliated to Roosevelt Hospital, New York, N.Y., embarked for England 26 September 1942, arrived in North Africa, 21 November 1942 –ed) and the 1st Battalion, 16th Medical Regiment (also arrived in North Africa 21 November 1942 –ed). After a long march in the sun (over 12 miles) from ship to the city of Oran, the outfit arrived at their location nearing the point of collapse. The time was about 1800 hours. The Hôpital Civil was in a sorrow state; part of the buildings taken over by the hospital contained only a few beds and patients were lying everywhere, on litters, on the floor, in filthy blankets, or on piles of discarded clothing. Cases of dysentery, pneumonia, and contagious diseases were lying beside wounded military personnel. The two remaining French doctors had done what they could, assisted by 6 Surgeons and Nurses pertaining to the 38th Evac Hosp but lack of equipment had precluded any serious care. The streets around the buildings fared not better as the stench of unwashed bodies, scattered garbage, sewage, and other unidentified odors permeated the air. What a first impression of North Africa! The same evening volunteers set to work and the next morning, Officers, Nurses and Enlisted Men were tasked with distributing the limited supplies and instruments they had brought along in their packs. Food was pooled and after discovering a gas burner a kind of stew was prepared for the patients. Many of the Surgeons carried their own instruments and with some borrowed from the 38th Evac and the 1st Medical Battalion, 1st Infantry Division (arrived in North Africa 8 November 1942 –ed), enough were assembled to start surgery. Conditions remained chaotic defying any description; patients were dirty, their wounds entirely neglected or inadequately cared for, and they had had no food for three days. Among them were 116 Allied military patients, PWs brought in by the French during the early phase of the invasion. While gradually taking over more buildings, reorganizing the patient flow, as well as trying to improve work conditions, most of the personnel slept wherever there was space available, in crowded conditions and much personal discomfort. After having taken over the hospital, new cases started coming in as the word spread that a hospital was now in operation. One of the most unpleasant situations that the outfit inherited was the Hôpital Civil morgue which contained 7 or 8 bodies in various stages of decay, which were finally disposed off by some volunteers. French nuns and some civilians continued to share some of the hospital’s buildings and facilities while caring for their own patients.

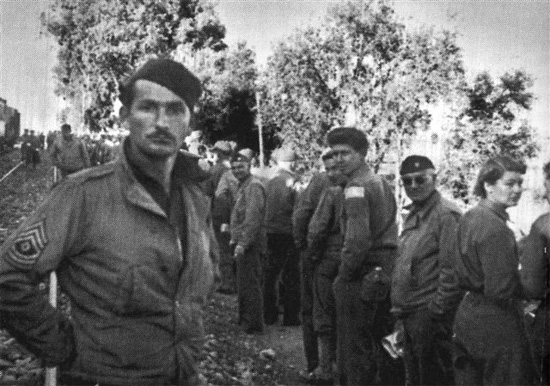

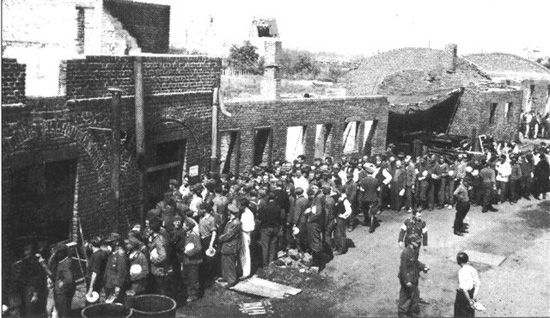

Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men stand in line for chow during a stop along the train route from Oran to Constantine, Algeria. Picture taken during the unit’s move to a change of station, 15 – 18 January 1943.

Before eventually American food started coming in, everyone, including the patients, had to subsist on C-rations and British Fourteen-in-One rations. Inexperience in cooking dehydrated foods resulted in many messes, but the technique was gradually mastered and variety in the methods of preparation helped alleviate the daily monotony of the food (further supplemented by purchase and bartering at the local markets). One of the first brass to come in and visit the Hospital was Brigadier General Theodore “Teddy” Roosevelt, Jr. (1887–1944, eldest son of the 26th President Theodore Roosevelt, and assistant CG of the 1st Infantry Division –ed) and he was to return a few days later for awarding Purple Hearts to all the wounded “Big Red One” patients. The unit’s organizational equipment had arrived on a freighter shortly after the personnel had landed, but it had been erroneously transported to Arzew (25 miles east of Oran), then finally to Mers-el-Kébir, and only reached the hospital five days after its opening. 5 trucks, 2 jeeps, and 2 water trailers had also arrived on another ship. During unloading at the docks, many small items and even a water trailer got spirited away, but in the end the numerous crates and boxes containing urgently needed supplies were unloaded at the Hôpital Civil and the other material stored in part of the bakery building. As much of the necessary equipment and material were now available, the interior of the buildings could be thoroughly cleaned and scrubbed, with the hospital installation gradually taking on a new appearance. Patients could now sleep under better conditions (on folding cots provided with blankets) and could be washed (washbasins, soap, towels becoming available) and properly dressed (two boxes of pajamas were found). Even a few clean white sheets were added for comfort. On 22 November, the harbor area and city were raided by the Luftwaffe; luckily, only a negligible amount of damage was done. The French and native staff of the hospital continued to care for their own patients in the other buildings. Several French women, mostly members of the French Red Cross, volunteered their services and were assigned duties in the wards.

On 24 November, the personnel of the 7th Station Hospital (activated 10 February 1941, embarked for Northern Ireland 26 September 1942, arrived in North Africa 22 November 1942 –ed) arrived to relieve the 77th and take over the Hôpital Civil. The organization was to move under tentage and open at another location (flat open terrain outside the city) on 1 December 1942. The field selected had been an old vineyard, and was surveyed by an advance party but while the ground was hard and dry during their visit, the rains which began on 25 November quickly turned the place into a red sea of mud (commonly designated the “Oran Ooze”). Conditions were awful, and after having been temporarily quartered in ward tents, EM were told to move into individual pup tents. Morale fell to an extreme low level and the supply section had to bring in some straw so that everyone had an opportunity to sleep dry and separate his bed from the mud. Blackout regulations were ignored and men could light fires at night which allowed them to dry out their shoes and socks before going to bed (a pup tent resident by the name A. Mudder even produced a sort of poem in the Stars and Stripes, called “Mud, Mud, Mud”). In order to put the larger tents to use for regular patient care, Officers and Nurses were quartered in small wall tents. Compared to the Enlisted personnel, they almost lived in luxury, yet they also had to bathe, shave, and wash in their helmets, with some hot water obtained from the mess area. Drainage because of the lower terrain (versus the area occupied by the hospital proper) was a real problem and frequent stormy weather ruined tentage and blew away material and anything that was loose. The very first ward tent erected served as a hospital for ill personnel belonging to the unit, and gradually more tents were set up and opened with the unit beginning to practice its first medicine under canvas. The hospital now acted in the capacity of a Station Hospital for its own personnel and any other troops in the area and the census gradually increased. On 14 December 1942, a British Hospital Ship coming in from Algiers brought 233 patients (including 20 psychiatric cases); on 21 December 1942, the British Troopship “Strathallan” was hit by a torpedo from U-562, 40 miles north of Oran suffering a loss of 11. Of the 5,111 survivors, 151 were sent to the 77th for treatment. During operation, it was discovered that contents of the crates often consisted of WW1 equipment, such as weakened and rotten canvas tentage, outdated Sibley stoves, lack of spark arrestors, malfunctioning autoclaves, cumbersome and oversized steel cabinets, missing shock-proof X-ray apparatus cables. Improvisation was the only way to remedy the situation and whatever could be mended or repaired was. The numerous revisions and changes did however add to the workload, and the rain, mud, cold weather, and trying circumstances associated with operating a hospital in the field unfortunately affected the high professional standards of the organization. Christmas Eve was preceded by several days of severe rain and cold weather, and without any special food (except wine) Christmas Day was miserable, filled with homesickness and depression, following six weeks of difficulties and problems. Luckily, the special food prepared on New Year’s Day compensated the above, with roast turkey – dressing – giblet gravy – cranberry sauce – potatoes – celery – apple pie – white bread – and coffee being served in generous proportions.

Shortly after 1 January 1943, as the number of patients decreased, the EM were finally moved into some of the empty ward tents. A recreation tent was set up and a German radio bought in Oran. With less hospital work, drill and road marches were organized and truck sightseeing trips made to other places. The improvement in mail delivery raised morale. On 7 January, the unit was alerted to prepare for movement. Preparations were made and since it was desirable to get as much of the equipment ready as possible, all personnel moved into ward tents, fed from a single mess, and ate from their mess kits. This released all the Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted Men’s tentage and cots for packing. About 10 January 1943, 1 Officer was detached to the 51st Medical Battalion, Separate (arrived in North Africa 11 November 1942 –ed) to travel in their motor convoy as an advance party to arrange for a bivouac for the main body. Orders finally arrived and plans were made to entrain at Oran Railway Station at 2200 hours, 14 January 1943. The train however was delayed until approximately 0300 the next day. It arrived and looked like a nightmare, with a dilapidated engine, battered and filthy wooden coaches, cars without windows, torn upholstering, no shades, and full of neglect. After having been dispersed over the various coaches, the train pulled out of the station passing slowly through the Oran suburbs on 16 January. Frequent stops were held, the only occasion to barter with locals, stand in line for chow, and enjoy a sanitary stop. Scenery and landscape changed, and with each day passing by, the passengers became dirtier, stiffer, colder, bored, and more tired than the preceding day. After three days and two nights, the train passed through the outskirts of Constantine, and the weary travelers detrained at the city’s station to be immediately assembled and hustled into the streets by the Officers of the advance party. Officers and Nurses were loaded onto British Army trucks and taken to the bivouac area where a few ward tents had been pitched while the EM began to march through the blacked-out city. Upon arrival they were ordered to pitch their pup tents. After a rather short night, breakfast was served, and men were sent back to the station to unload rations and barrack bags. Wood was scrounged for the kitchen and straw to make the beds more comfortable; rocks were dug out; slit latrines built and screened; and tents correctly repitched. Showers were available in nearby French barracks with water turned on for only thirty seconds.

The bivouac area was shared with the 51st Medical Battalion, soon to be joined by the 9th Evacuation Hospital and the 48th Surgical Hospital, as well as elements of the 2d Auxiliary Surgical Group (arrived in North Africa 11 November 1942 –ed).

On 18 January 1943, the advance party led by an Officer left to select another site for the hospital near Tébessa, southeast of Constantine. On 20 January, the main body had been packed in British personnel carriers (25 men per vehicle). The motor convoy passed the airfield at Youks-les-Bains, entering some woods containing camouflaged combat and service units, part of II Corps, waiting to be thrust into battle. Tents and messes had been set up among pine trees and wooded slopes and camouflaged with tree limbs and bushes, hence the designation of the bivouac as “Pine Ridge”. The 77th remained idle for quite some time, while the 9th Evac and the 48th Surg moved out to set up elsewhere. After the Germans had broken through Kasserine Pass (only 20 miles east of the bivouac), orders came through that the hospital was to open as rapidly as possible to take the overflow of patients from the other medical units. During the first night, only ambulatory cases were sent up from the 9th Evacuation Hospital, but on the following morning this unit was gone. The 9th and 77th Evacuation Hospitals were located about 10 miles southeast of Tébessa, far to the rear, while the 48th Surgical Hospital was operating a 200-bed unit at Thala, Tunisia, and another at Fériana, also in Tunisia, more than 50 miles away from the original II Corps combat lines of 14 February 1943.

Wild rumor mongers had a field day, some stories were however true, and coupled with the increased thunder of artillery fire in the distance, enhanced the general excitement, and when trucks of combat troops streaked past the hospital’s installation on their way to the rear, orders came in to pack and move on the double. With 150 patients still on hand, trucks were borrowed from other units, and before daylight the next day, an advance group had already left to establish a new camp some sixty miles to the rear in the vicinity of La Meskiana, Algeria (it was there that the organization gained the service of Miss Natalie Gould, ARC –ed). Ambulances rounded up the patients and Nurses and started for the new location. By 18 February the last trucks pulled out of the area. Reaching La Meskiana at 1530 the personnel had already erected the mess tent and the kitchen when they received new orders to move further back through La Meskiana and to select a site at the edge of a wooded area. Everybody then worked all night to provide the patients, waiting in the ambulances, with breakfast before dawn the next morning. Officers, Nurses, and Technicians often worked for as long as seventy-two hours in a stretch with only brief naps causing enormous strain on the personnel. About midnight it had started to snow and a bitterly cold wind was blowing. The result of the German breakthrough brought about the dispersal of the Medical Collecting and Clearing Companies over hundreds of miles of rough and largely roadless country. By 20 February both the 9th and 77th Evac were fortunately back in operation, at new sites on the road to Constantine, and the 48th Surgical shifted further north to Montesquieu, Algeria. The II Corps’ next mission was to attack in the Gafsa-Maknassy area in support of the British Eighth Army’s drive up the coast. Although Colonel Richard T. Arnest (Surgeon II Corps –ed) requested 1 (one) 400-bed Field Hospital and 1 (one) 400-bed Evacuation Hospital, and more ambulances, he only received some ambulances. The only medical reinforcements consisted of five teams of the 3d Auxiliary Surgical Group (arrived in North Africa 16 February 1943 –ed) flown in without Nurses on 18 March (eleven teams of the 2d Auxiliary Surgical Group were already operational with II Corps –ed). In the interval between recovery of the ground lost in the Kasserine withdrawal and the launching of the II Corps offensive, hospital installations were once more moved forward to the Tébessa area. This took place on 27 March.

Picture illustrating some personnel of the 77th Evacuation Hospital while stationed in Algeria, in North Africa. The photo may have been taken during spring of 1943.

After the German surrender (approximately 275,000 PWs were taken –ed), the use and disposition of mobile hospitals was drastically modified and many lessons drawn from the recent operations. The 77th Evac Hosp closed on 12 April 1943 for operations after receiving orders that the unit was to move on 14 April.

Consequently, the 77th Evacuation Hospital was instructed to set up in a field about 2 miles east of Morris, near Bône, Algeria, where it was assigned to the Eastern Base Section (EBS), the forward element of the North African Communications Zone. The unit used its new site advantageously where it possessed air, rail, and water outlets, though its ambulance run of 85 to 110 miles over rough roads affected the transportation of seriously wounded patients. The installation was set up rapidly and after a few days, the 77th was joined by the 51st Medical Battalion and a Motor Ambulance Company. Less than hundred yards away was a PW enclosure, and 500 yards to the east was a large ammo dump. First patients arrived on 16 April, and although three other hospitals – the 9th Evacuation (arrived in North Africa 21 November 1942 –ed), the 11th Evacuation (activated 10 February 1941, embarked for North Africa 2 November 1942, arrived in North Africa 18 November 1942 –ed), and the 15th Evacuation (activated 1 June 1941, embarked for North Africa 7 February 1943, arrived in North Africa 21 February 1943 –ed) were stationed much nearer to the front, the 11th and the 15th EH were experiencing their first field operations and consequently required more time to get organized. Further combat losses cost more lives and casualties and many of the latter poured back through the chain of evacuation to the 77th Evac which increased the patient census considerably. Many of them needed blood transfusions badly, and the unit’s Officers and EM had to be used as donors once more. In only 45 days of active operation the hospital treated 4,577 patients! The hospital remained open until 25 June 1943, with a very low census rarely reaching 10 admissions per day during June. On 16 May 1943, a Victory Parade was staged in Bône with representative groups from nearly all the units in the area taking part, with Nurses of the 77th marching in formation (the only women to participate in the parade).

Mosquito control had to be introduced and mosquito nets were issued to each member of the command and all hospital beds were equipped with them. In addition, each personnel member was instructed to take 2 Atabrine tablets two days a week (in spite of the measures several members developed malaria). Because of flies and warm weather, dysentery cases were numerous, necessitating additional sanitary measures. A collapsible water storage tank was constructed and a shower unit installed.

Some Officers endure a cold spell while bivouacking on “Pine Ridge” in the vicinity of Tébessa, Algeria, in January 1943. During the day when the sun was out it was comfortably warm, on cloudy days it was always cold and windy, and at night fires and extra clothing were needed to protect from the cold.

King George VI visited Bône 17 June 1943 and took the opportunity to inspect British and American units in the area, and Allied troops lined both sides of the nearby highway for several miles south of Bône, standing at attention for the royal convoy. Rumors were again circulating since the hospital had been alerted for a possible move, with alert orders received as early as 15 June. Although the 77th Evac closed at Morris on 25 June, the unit remained in the area for another 2 months!

On 29 June 1943, a detachment commanded by Major Martin F. Anderson left in a motor convoy traveling over hot and dusty roads under repair by German and Italian PWs to the war torn city and harbor of Bizerte, Tunisia, where they began their detached service with the US Navy (the main reason being that the 77th EH was relatively inactive and could spare some personnel –ed). After 1 July the details of this special assignment became clear. A medical team consisting of at least 1 (one) Officer and 4 (four) Enlisted Men was to be assigned to each of seven LSTs (LST 325 – 313 – 308 – 315 – 344 – 338 – 337 –ed); 9 (nine) more men were to accompany Medical Officers of the 91st Evacuation Hospital (activated as 6th Surgical Hospital 1 August 1940, redesignated and reorganized as 91st Evacuation Hospital 31 August 1942, embarked for North Africa 12 December 1942, arrived in North Africa 24 December 1942 –ed) on other LSTs (LST 340 – 4 – 380 – 2 – 371 – 307 – 381 – 369 –ed); 2 (two) Officers and 8 (eight) more Enlisted medical personnel were to serve at the Naval Base at Bizerte; and 2 (two) Officers and 10 (ten) EM were to equip and operate a 100-bed hospital and assist at the Naval Hospital at La Goulette, Tunis, Tunisia, with returning casualties. On 2 July all designated Officers and Enlisted personnel entrucked for La Goulette where they boarded the assigned ships. Between 2 and 8 July, inspections took place, loading plans were made, operative procedures and care of casualties organized, and supplies stocked. Medical Officers were also given assignments to battle stations about the LSTs. On 8 July 1943, the convoy of 45 ships sailed out of the Bay of Tunis setting course for the island of Malta. On 9 July 1943, it was confirmed that this force was bound for Sicily to participate in the assault landing against Gela. In total three convoys were organized, sailing again on 15 July, with the final trip taking place on 21 July. The entire detachment returned to Bizerte, Tunisia, on 27 July and was relieved by the Navy and returned to Morris, Algeria, on 29 July 1943.

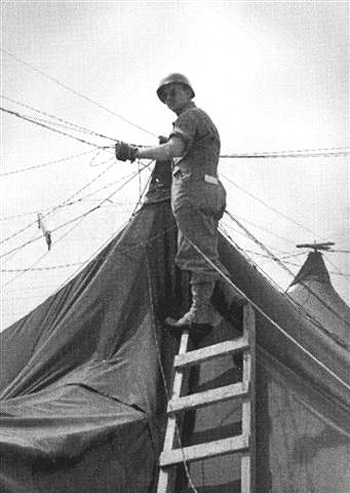

Wiring. An Enlisted Man with the 77th Evacuation Hospital connects the unit’s communications network. The maze of wire interconnects the various tents in the camp.

Colonel Burgh S. Burnet, MC, was relieved of command on 20 August 1943 to become the Atlantic Base Surgeon (ABS), and was temporarily replaced by Lt. Colonel James B. Weaver, MC.

Stations in North Africa – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Oran, Algeria – 12 November 1942 > 1 December 1942

Constantine, Algeria + Tébessa, Algeria + La Meskiana, Algeria

Bône, Algeria – 16 April 1943 > 25 June 1943 (stayed 2 more months, not operational)

Official Campaign Credits – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Algeria-French Morocco

Tunisia

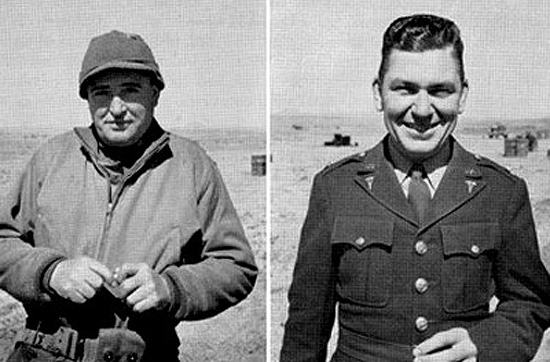

II Corps in North Africa. From L to R: Colonel Richard T. Arnest (Surgeon, II Army Corps) and Lt. Colonel William H. Amspacher (Deputy Surgeon, II Army Corps).

Sicily:

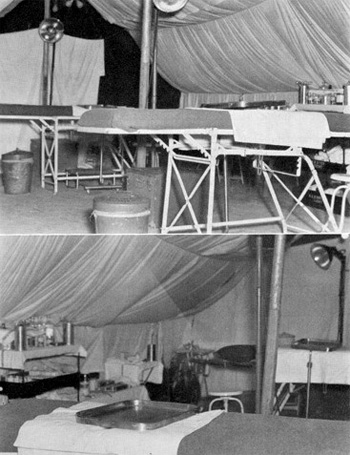

Partial views of the Operating Rooms of the 77th Evacuation Hospital, while stationed in Algeria, North Africa.

On 28 August 1943, the orders that had been awaited almost daily since June arrived and plans were made for a move to Sicily. The transfer was to take place in two movements; the personnel would go by Hospital Ship, and the equipment by freighter. On the morning of 2 September, the personnel entrucked for the harbor of Bône, Algeria, and with their personal baggage boarded HMHS “Amarapoora”. The quarters designed for ambulatory patients were assigned to the Enlisted personnel while those intended for litter patients were divided among the Officers and Nurses of the 77th. Shortly after boarding, an order went out from the skipper to surrender all guns, knives, or other ‘personal’ weapons in accordance with Geneva Convention requirements. All the items were carefully tagged and set ashore for retrieval later. A first stop was held at Bizerte where the vessel remained at anchor overnight. On 4 September 1943, the Hospital Ship pulled away to set sail for Sicily; it reached Palermo, Sicily, the next day.

Due to the bomb damage it was impossible to reach a pier; consequently an LCT pulled alongside the “Amarapoora” to take the passengers on board for the short run to the docks. Ambulances and trucks transported the personnel and their baggage through the city to the courtyard of the University of Palermo Hospital and Medical School, where the 59th Evacuation Hospital (activated 6 April 1942, affiliated to San Francisco Hospital, San Francisco, California, embarked for North Africa 12 December 1942, arrived in North Africa 24 December 1942 –ed) was stationed. All personnel were quartered in the buildings and furnished with either folding cots or steel hospital beds. The food prepared by their hosts, the 59th Evac, proved much better than whatever the 77th had so far experienced in Africa. Duties were still light enough to allow sufficient off-duty hours to visit Palermo and enjoy sightseeing and shopping.

On 8 September 1943, the formal announcement of Italy’s surrender (actual date 3 September –ed) to the Allies came through and the city of Palermo turned out en masse to celebrate. On 20 September, Captain Oscar J. Milnor and his detachment of 6 Enlisted Men arrived in Palermo harbor with the organization’s equipment. Within a few days, most of the equipment had been unloaded and transported to a site 5 miles west of Licata on the southern shore of Sicily. On 22 September 1943, Colonel Samuel L. Cooke, MC, arrived and assumed command of the 77th Evacuation Hospital.

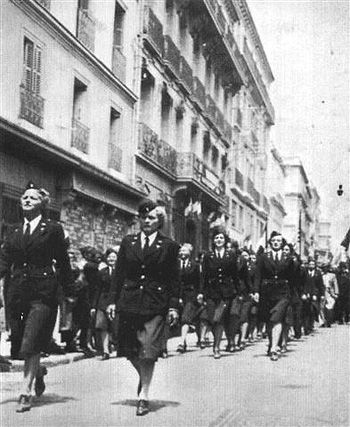

ANC personnel of the 77th Evacuation Hospital march in the “Victory Parade”, Bône, Algeria. The celebration took place 16 May 1943.

Major Tony G. Dillon took an advance party to Licata on 25 September to start building living quarters at the new location. Officers and Nurses boarded a train which had quite some trouble in battling its way up the mountainous parts of the island. About midway across the train carrying the Officers passed the EM’s train as it sat on a siding, waiting to go again. Although having departed several hours before the other train, the engines were in such a poor state of repair that it almost proved impossible to reach the summit of the many grades. The Officers and Nurses arrived at Licata about 2200 hours on 25 September, but the Enlisted Men’s train did not arrive until 0430 on 26 September. The 175th Engineer General Service Regiment (activated 26 May 1942, embarked for North Africa 2 November 1942, arrived in North Africa 11 November 1942, arrived in Sicily 1 August 1943 –ed) had already graded roadways and cleaned the immediate surroundings of mines and trees. After unloading once more and unpacking the equipment and supplies the unit was functioning on 27 September 1943, and 211 patients were admitted. The 77th Evacuation Hospital replaced the 15th Evacuation Hospital (activated 1 June 1941, embarked for North Africa 7 February 1943, arrived in North Africa 21 February 1943 –ed) which was withdrawn for service in Italy. Since water was of poor quality and lacking it became necessary to install a 5,000-gallon collapsible water tank. After Engineers had cleared the mines in the immediate neighborhood, a path was constructed to go bathing in the Mediterranean, an activity that soon became quite popular. The weather was mild until mid-October when high winds blowing in from the sea began to take a heavy toll on canvas. Pins and tents were torn loose and were difficult to replace in the hard and rocky soil. After a few preliminary showers, heavy rains began to pour down in torrents turning the entire hospital area into a quagmire. All attempts to keep access roads and walks passable remained fruitless and even truckloads of crushed rock and gravel could not help. Fortunately admissions had begun to decrease with new cases being received in daylight hours, which left a minimum of night work for everyone. When rumors were confirmed that the 1st Infantry Division was to move it almost became impossible to keep any of their men in the hospital who could walk. Their destination was to be England and pressure was brought to bear on ward Surgeons by the Division’s line Officers to try and get their men dismissed as soon as possible. Recreation was handled by the unit itself with parties in the neighboring area, trips to the Roman ruins in Agrigento, and fishing trips with local fishermen.

About 14 October it was learned that the Hospital was to be returned to England and Lt. Colonel Edward J. Hashinger was therefore sent to the United Kingdom. Orders were received to start packing, and in spite of the awful weather conditions and the mud, the personnel were ordered to turn in all overshoes since they wouldn’t be needed in England, much to the consternation of the unit members. But orders were orders and the men continued wading about with wet feet in ankle deep mud without serious protection. The organization closed on 26 October and by 28 October, packing had been completed and all personnel boarded the same trains that had brought them to Licata. Destination proved to be a large staging area near Mondello Beach, filled with pyramidal tents, where everyone was processed and held ready for shipment out of Sicily. The bulk of the organizational equipment had been shipped to the Quartermaster Depot in Palermo, and only personal baggage including some housekeeping articles as kitchen equipment, office records, and some professional instruments had been retained. Everything of this had been marked with a new code, 6210-E (replacing the old one issued at Ft. Leonard Wood). The rain continued intermittently and the grayish-brown mud from Licata was now gradually being replaced by the yellowish-red mud of Mondello. When the weather permitted, walks were organized in the mountains near the camp, and after a few days of relative freedom which lots of passes, the entire staging area was placed under strict security. During their stay the 77th Evac received a call for help from the 59th Evacuation Hospital who were receiving large numbers of casualties from the fighting in Italy, and several Nurses were sent on detached service (DS) to that hospital. A mild epidemic of diphtheria broke out in the camp but within a relatively short time the situation was under control. Delay in shipping was mainly due to the fact that the convoy which was to carry the entire movement had been hit by enemy aircraft off Bizerte, Tunisia, and the loading plan had to be revamped. After several days of waiting and many changes in schedules, loading time was set for 10 November! One hour before dawn, the men were up and instructed to police the entire area. After packing the barrack bags, field packs, and musettes, came the inevitable period of waiting. At approximately 0800 hours on the morning of 10 November 1943, the necessary trucks arrived and all personnel and baggage were loaded and taken to the dock area of Palermo harbor. Long lines then formed, roster calls were started, and finally everyone started up the gangplank to board the USAT “John Ericsson”.

Stations in Sicily – 77th Evacuation Hospital

University of Palermo, Sicily – 6 September 1943 > 25 September 1943 (not operational)

Licata, Sicily – 27 September 1943 > 28 October 1943

Staging Mondello Beach, Sicily

Official Campaign Credit – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Sicily

The convoy consisting of several crowded troopships with adequate escort vessels sailed from Palermo shortly after midnight of 11 November 1943. Near Gibraltar, some enemy planes were sighted and antiaircraft guns from the escort vessels opened up driving the marauders away without any damage to the convoy. The ships passed the Straits and three days later the Azores were in sight. Shortly after boarding, medical teams were formed with some Enlisted personnel pertaining to the 9th Medical Battalion, 9th Infantry Division and the 77th who received primary duty in the ship’s dispensary. The majority of cases during the voyage were malaria or hepatitis or both, including some respiratory and intestinal infections. As the convoy moved into the North Atlantic, the weather became colder and the seas less docile, thus increasing seasickness. As a result a number of empty chairs appeared in the Officers and Nurses’ mess and shorter lines in the Enlisted Men’s mess gave mute evidence of the situation. The remainder of the trip was uneventful except for the storm that developed in the Irish Sea which prevented the convoy from entering the narrow lane between the minefields in the Mersey River estuary. The next day, it was about 1730 in the late afternoon, the first units were lined up on deck with the necessary hand luggage and individual gear and ready to descend the gangplank and board the nearby waiting trucks. On 25 November 1943 the 77th Evac landed at exactly the same spot, Prince’s Landing Stage, Liverpool, where it had landed some fifteen months earlier… and was back in the United Kingdom.

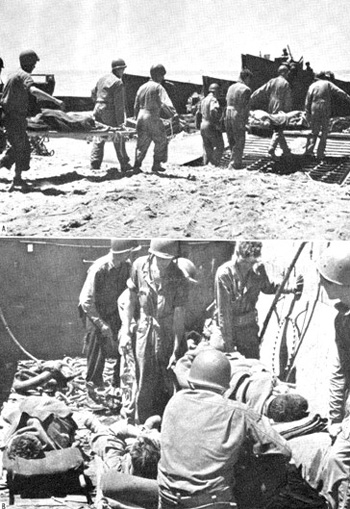

Sicily July 1943. Evacuation of casualties from the inland fighting in Sicily. Wounded are being loaded on landing craft for evacuation from shore to ship.

United Kingdom:

After leaving the ship, all personnel marched the short distance to the train. After boarding, American Red Cross attendants came through the train with doughnuts and hot coffee, chewing gum, cigarettes, and copies of the “Stars and Stripes”. At about 0900 hours in the morning the train departed reaching Ludgershall Station, England, at 0900 the morning of 26 November 1943. Lt. Colonel E. J. Hashinger was waiting on the platform to welcome the unit, and after loading all the baggage onto the waiting trucks, the motor convoy started its trip for Everleigh Manor, where a semi-permanent hospital had been built by the British under Reverse Lend Lease agreements. Nissen-type huts, including wards and living quarters were dispersed over the flat land of the estate, interconnected by cement walks and enclosed passage ways. No hospital equipment had been installed yet and only a number of beds had been set up to accommodate Officers and men. The Nurses were assigned their own space in the smaller buildings (four to each building). Breakfast was ready and proved most welcome.

After having been briefed on everything relating to England, the war, the British way of life, and gone through their first inspection (the European Theater of Operations was often designated “Theater of Inspections” –ed), the organization received its first orders to prepare the hospital for operations. Hospital equipment, chiefly of the British type, was stored on site, but before anything could be unpacked and installed, the new ward buildings which had never been occupied since their construction had to be thoroughly cleared and cleaned, and it was only after working ten to sixteen hours each day, that the task was finally completed. By 27 December 1943, the receiving was opened and the first patients arrived. Toward the end of the cleaning and pre-operating period, it had been announced that a Station Hospital would arrive soon to operate the plant. As the Hospital census increased and more wards were put to use the hospital work became more routine with daily admissions remaining small and cases predominantly medical in nature (little surgery). Only a total of 646 patients were received by the unit during its stay at Everleigh.

Personnel of the 77th Evacuation Hospital awaiting transportation at the Mondello Beach staging area, near Palermo, Sicily. Picture taken end October 1943 prior to the unit’s return to the United Kingdom.

The 77th lost several men by transfer to other units, reclassification by illness, and other causes, and the reception of 33 replacements was necessary to complete the Enlisted Men’s quota. The outfit lost its Executive Officer, Lt. Colonel Edward J. Hashinger, MC, who (after 16 months of service overseas) returned to the Zone of Interior on the rotation plan. The personnel of the 318th Station Hospital gradually took over operation after a short period of orientation and on 24 January 1944, the 77th Evac left Everleigh, entrucking and entraining for Gloucester.

An entirely new sort of life began for the unit, as there were no single barrack facilities available plans had been made to billet the men in private homes in Gloucester. American personnel shared their PX rations and excess food with their new British friends and in return were frequently invited to tea or dinner. The Enlisted Men were fed at a mess at Reservoir Camp, a British military training camp at the edge of town, while the Officers and Nurses’ mess was set up in Wesley Hall, a community center building of one of the local churches. The small amount of unit equipment was temporarily stored at Compton Hall, another building in the industrial district.

After a few days, a training program was begun, and each day after breakfast, assembly was sounded and groups of personnel marched through the city’s streets to the drill field at the edge of town. Close order drill, gas mask exercises, road marches, were all part of the new program, and after lunch, lectures and pictures followed that occupied the greater part of the afternoon. As there was no organized recreation program, movies, pubs, and Service Clubs were well attended, and mess halls often used for recreation. During the 77th’s stay at Gloucester, 6 Nurses went to Bristol to the 298th General Hospital (activated 27 June 1942, affiliated to University of Michigan, Ann Harbor, Michigan, embarked for England 20 October 1942 –ed) for a special course in the treatment of burns; 2 other Nurses received a special training in NP nursing at the 312th Station Hospital and another Nurse went to the 30th Station Hospital to follow some other courses and lectures. Two more Nurses attended administration courses at the ANC School at Shrivenham. The lack of medical activity, the wet and cold climate, the dull routine of the various training programs, and the dispersal of the personnel, soon began to wear down on the morale and esprit de corps of the entire unit. The men felt discouraged at being of no real use and wanted to become more active. During this time, Colonel Samuel L. Cooke, MC, who had been in command of the 77th since September 1943, was relieved to assume duties with the 58th General Hospital (activated 15 January 1943, affiliated to Western Pennsylvania Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, embarked for England 8 October 1943 –ed). The following day, Colonel Dean M. Walker, MC, arrived and assumed command.

About 15 March 1944, several things happened which improved the morale of the men. The weather improved and funny enough from the townspeople came the first rumors of an imminent movement of the unit to Tunbridge Wells, in southern England. The official announcement did indeed follow, and on 9 March the first advance detail was sent out, with a second detail following on 24 March. On 1 April 1944, the remainder of the 77th departed by train for Tunbridge Wells. The new location proved to be a grass slope at Langton Green, at the edge of the village of Rusthall about 1½ miles from Tunbridge Wells, Kent. By the time the organization arrived on site, a great amount of work had been done. The living quarters tents were set up, stoves installed, fuel made available, wiring strung between the tents, washrooms readied (with hot and cold water), latrines dug, mess halls built, and cinder paths installed. Such luxuries had been unheard of by the 77th in a tented hospital, and were viewed with surprise, satisfaction, and skepticism. During the ensuing four weeks, the organization’s personnel continued the work with building access roads, grading and surfacing the roadways, piping water into the kitchens, and installing hydrants near the ward tents. Fences were erected and painted, and landscaping added the necessary setting.

Soon the new Hospital was being inspected by the local medical hierarchy of American and British Armies, including Colonel Robert E. Thomas (Southern Base Section, United Kingdom); Major General Paul R. Hawley (Surgeon ETO); Brigadier General Ewart G. Plank (CG ADSEC); and Major General Oswald W. McSheehy (RAMC), with the hospital installation becoming known as the ‘showplace’ of field-type Hospitals.

Several worthwhile improvements in the hospital’s utility and flexibility were made such as a complete set of packing crates that, when unpacked, could be set on end or stacked one on another, shelves put in place, and the open sides covered with muslin curtains to form linen cabinets, medicine cupboards, bedpan and urinals lockers, and other storage units. The same furniture could further serve as packing crates for cots, mattresses, sheets, blankets, pillows, enamelware, and supplies of instruments and medications. Improvisation did it! Each crate was marked with the unit’s proper code device and the number of the ward to which it belonged as well as its contents. The precious time and effort spent in devising this standardized packing method proved to be of the utmost value in later operations.

Stations in England – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Everleigh Manor, Wiltshire – 27 December 1943 > 24 January 1944

Gloucester, Gloucestershire – 25 January 1944 > 1 April 1944

Tunbridge Wells, Kent – 27 April 1944 > 27 May 1944

By 27 April 1944, the hospital installations were opened for patients and during the following months 419 cases were admitted. Apart from the medical cases, the majority, chiefly coming from units stationed in the surrounding are, the surgical cases were largely non-traumatic diseases or minor injuries. Only a few severely wounded were received, mostly connected from air battles or emergency landing incidents (many burn cases), or were transferred by ambulance to the 77th from British hospitals on the channel coast in the vicinity of Canterbury. Because of the light load of hospital work, it was possible to rotate the personnel on duty. Training and recreation filled the time during the liberal off-duty hours. Morale ran high in almost all quarters in spite of the lack of actual professional work, unit members swarmed the countryside, games were organized, parties held, ceremonies attended, and the immediate prospect of the coming Allied Invasion of the continent furnished a definite goal, with the prospect that a victorious end to the war in Europe, would enable everyone to return home soon.

On 10 May, the unit was put on a forty-eight hour alert by ADSEC. On 27 May 1944, the 77th Evac was officially closed and all patients were turned over to the 6th Field Hospital, newly arrived from the States (the unit had previously served in Alaska and on Kiska Island, and arrived without a Nurse complement –ed). The unit was then issued its new code numbers, 31999 and 32000. Suspense and anticipation relating to the forthcoming invasion gradually heightened and the size and frequency of heavy and medium bombers filling the skies increased day by day leaving no doubt that this was indeed the softening-up process in preparation for the assault against Fortress Europe! The forty-eight hour alert basis now took a more real meaning. On 15 June, the organization witnessed its first “buzz bombs” (German V-1 rockets), and in the following days several of these missiles had fallen and exploded within only a mile of the 77th, leaving few windows in the houses of the surrounding area intact and blowing away large numbers of roof tiles. When antiaircraft artillery joined in to fight these flying bombs, a shower of small flak fragments often fell on tented roofs like hail, ripping some tentage. Fortunately no one was ever hurt. Toward the end of June, 2 War Correspondents of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the Kansas City Star were attached to the unit for rations and transportation. On 28 June 1944, the entire unit entrucked for Tunbridge Station and boarded trains with destination Eastleigh, from where the Officers and Enlisted Men continued by motor convoy to Area C-5, and the Nurses to Area C-22, both staging areas about 15 miles from Southampton. Life at the staging areas was dull, with reading, card playing, and watching movies, the only way to keep busy. Luckily the food was good. Impregnated clothing was issued, anti-seasickness pills as well as small paper vomit bags distributed, and water purification tablets given out. English money, of which there was little left in the unit, was turned in for Allied “Invasion” currency.

France:

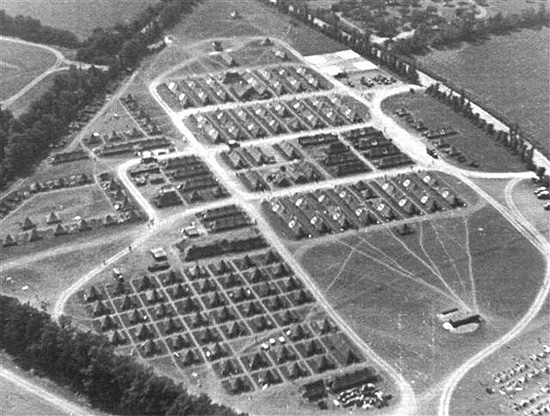

Aerial view of the 77th Evacuation Hospital, near Sainte-Mère-Eglise, Normandy, France, where it opened for operations 18 July 1944. The Hospital was made up of 95 pyramidal, 71 ward, 8 small wall, 7 storage, 6 squad and 2 large wall tents.

After a week behind a barbed wire enclosure at the staging area, the unit went by way of a motor convoy to the edge of the dock area of Southampton. During a two-and-a-half hour wait, coffee and doughnuts were served from a Red Cross Clubmobile and a Special Service unit passed along paperbacks and other reading material for the channel crossing. Finally, the personnel were marched through the busy streets up the gangplank of the British “Empire Lance”. The sun was shining and this felt like ‘the’ day. Quarters on board were clean and consisted of large compartments and steel bunks, without furnishings, but entirely adequate and comfortable for the short crossing to France.

On 7 July 1944, it was approximately 1500 hours, the ship arrived off Utah Beach. LCVP and other landing barges scooted back and forth between shore and ship seeming to ignore the hospital group waiting to disembark. Finally they too were ordered into the landing craft after having been divided into two separate groups. After a short walk between beach and dunes, the Beachmaster brought the unit to the assembly point from where they were marched to their bivouac area. The 77th Evac had arrived in France …

The unit was instructed to bivouac for the night in Transit Area B, Utah Beach, at St. Germain-de-Vareville, while the Nurses and advance party were sent ahead by truck, with the remainder of the personnel led by Colonel Dean M. Walker, CO, following on foot. The march was about 7 miles, but after only about three miles it started raining. After the men got thoroughly soaked, the rain suddenly stopped, and the sunshine returned just as the group reached a well-paved road. A constant stream of vehicles passed the column as empty ones returned to the beach dumps to pick up ammunition, gas, and rations for the front. The bivouac area was located in an apple orchard bordered by hedgerows. Foxholes had been dug by earlier units passing through but since there were no latrines, it was decided to improvise some construction to accommodate the Nurses. The men of the advance detail had heated water for coffee and a K-ration meal was quickly consumed, and pup tents pitched.

In the early morning hours a friendly artillery barrage was heard in the distance but all were already up early anyway and packing was completed long before noon. Without advance notice, a group of 3 surgical teams were ordered out on DS to assist the 67th Evacuation Hospital (landed 16 June 1944 –ed), with Officers and Nurses leaving immediately, followed by the Enlisted Men. The 400-bed 67th Evac Hosp which had been working constantly badly needed assistance and within a few days a number of ward Officers and Nurses were temporarily attached to help treat the operative backlog (200 surgical cases). The attached 77th teams worked for long hours, operating on an average of 25 patients during each 12-hour shift. Finally the 67th stopped admissions in preparation for going into bivouac and on 19 July all attached personnel returned to their own units. More 77th teams were sent on DS to other units, including the 128th Evacuation Hospital (landed 10 June 1944 –ed), the 96th Evacuation Hospital (landed 16 June 1944 –ed), and also the 44th Evacuation Hospital (landed 19 June 1944 –ed).

2 Ambulance Platoons from the 563d Motor Ambulance Company, commanded by First Lieutenant George Lahey, had arrived and provided extra transportation to move the remainder of the personnel (those not on DS –ed) to a new bivouac west of Ste-Mère-Eglise. Here a new camp was set up in three adjoining fields; with Enlisted Men and transport vehicles in one field, Officers, Nurses, messes, supply, and headquarters in another, and the ambulance platoons in the third. Scrounging became a large-scale activity in an effort to secure material to increase the general comfort of quarters and installations. A nearby field had in the meantime been selected for the hospital site and while waiting for the organizational equipment to arrive, the men had to fill in the numerous bomb craters, the foxholes, clear the debris of war such as abandoned ammo cases, ration boxes, discarded clothing and individual equipment of both American and German origin. In one corner was the former site of a Battalion Aid Station as evidenced by dirty dressings, empty EMT books, bloody sponges, and a boot with part of a leg and foot still in it. After all this had been duly cleaned up, latrines were dug and hospital roads made out so that work could start. First Lieutenant Earl L. Hoard, MC, had been left at Tunbridge Wells with the equipment but had to wait until 3 July to catch a boat to cross the channel to Normandy. Unfortunately the ship went to the wrong beach, Omaha, where it arrived 5 July 1944; the ship was only authorized to sail to Utah Beach on 15 July, where unloading was started at 1730 that same evening and completed about 0730 the next morning. The misdirected equipment was hauled from the beach and transported to Ste-Mère-Eglise, and thirty-six hours after the first truckload arrived, the 77th was completely established and ready to receive patients. The date was 18 July 1944. When completely set up the 77th Evac used 189 tents: 71 ward tents – 95 pyramid tents – 7 storage tents – 6 squad tents – 8 small wall tents – 2 large wall tents – plus a large number of individual pup tents. In pitching these tents, the EM had driven 6,786 long pins and 7, 246 short tent pins. Because of the proximity to the combat zone, the major portion of patients consisted of recent wounded evacuated directly from the Collecting and Clearing Stations. During their stay in the vicinity of Ste-Mère-Eglise, the personnel were organized into groups, one for each 12-hour shift, working from 0800 to 2000 hours, as all departments functioned completely during the entire 24 hours. The preliminary job in the receiving tent was handled by Captain Oren D. Boyce and Captain Walter J. Olszewski who examined each patient carefully and determined accurately the ward to which the wounded man was to be taken. Four (4) operating tables and 2 tables for the treatment of fractures were in constant use, and 3 more tables were used 18 to 24 hours a day for minor surgery. One person acted as triage and liaison Officer, assigning the patients to the 2 operating Surgeons of the team. The severity of the wounds varied greatly, although the majority were seriously wounded; indeed, most of the wounds were caused by mortar and artillery fire, the latter predominating. A separate tent for neurosurgery was installed, connecting with the OR, and here the specialized Surgeon performed feats of surgical skill that resulted in the saving of many lives. Six (6) specialists belonging to the 1st Auxiliary Surgical Group were temporarily attached to the 77th. Three other Surgeons and one Nurse also performed an excellent job, belonging to a maxillo-facial team of the 1st Aux Surg Team. The x-ray section functioned unceasingly as well as the shock department which responded promptly with the indicated necessary treatment to be administered to the numerous patients. Large amounts of IV medication were administered during the first 20-day period including 56 gallons of plasma – 30 gallons of whole blood – and 72 gallons of glucose and saline solutions. Seriously ill and severely wounded patients were taken to nearby airstrips for emergency evacuation to England, less serious casualties were sent to the Omaha and Utah Beaches to be returned across the channel by ship, convalescent patients were transferred to General Hospitals farther back in the Cotentin Peninsula and cured patients returned to their units for duty. Total patient census was 3,234 including 181 German prisoners and 27 French civilians, resulting in 1,775 operations. Supplies were used in large quantities, necessitating frequent replacements by truck convoys making daily trips to the available dumps. A special mess section was kept open 24 hours a day, offering snacks and meals to the night shift and any arriving or departing ambulance driver. During this period, details whitewashed stones along access roads and installed white markers made out of bandage material (stretched from stake to stake) to help litter bearers and personnel who had to walk about the hospital area at night. Because of the large water consumption, a 5,000 gallon canvas water storage tank was elevated about twelve feet off the ground to provide a constant supply of water under pressure to the ward tents, operating rooms, and kitchens. As there was an absolute necessity to obtain more litter bearers, a group of men was temporarily attached from the 25th General Hospital (activated 10 June 1943, affiliated to Cincinnati General Hospital & University, Cincinnati, Ohio, embarked for England 23 December 1943 –ed), which was still awaiting the arrival of its organizational equipment). One of the farthest tents in the area was reserved for the morgue; the CO called it “Purple Heart” corner.

After stringing bandages around the tent pins, work details whitewash rocks and stones to aid night duty personnel. Picture of the 77th Evacuation Hospital taken in July 1944 while stationed in France.

After the battle for St-Lô was over, ADSEC ordered the 77th Evacuation Hospital to move to the vicinity of the town. The advance party left on 8 August and when the motor convoy arrived the following day, loading was accomplished in a minimum of time, with everyone departing around 1530 hours. The trip was short and on their way to the new location, the personnel were struck by the number of French refugees returning to their liberated homes in any available means of transportation. Upon reaching St-Lô, they were confronted by the mass of destruction and rubble in town, as not a single house appeared untouched. Engineer bulldozers had produced a passable road through the main street which smelled of death and destruction. The new site was 1½ mile south of the town across the road from the racetrack where a FUSA Medical Supply Depot was situated. The camp was situated in the paddocks on a gently sloping field divided by a number of concrete fences. The hospital section was placed on the higher part of the area, while down the slope in an apple orchard the tents for the Officers were pitched, with those of the Nurses in another field further back. The Enlisted Men’s tents were placed back of the rear part of the Hospital. Since the field had not yet been cleared of mines and explosives, Engineers were called in to perform the task. Some dead Germans were found and well-constructed foxholes and positions were dispersed especially in the orchards, dug wide and deep, and covered with logs and earth over the tops. Dead animals were covered with dirt, and fences pushed down to allow the building of access roads.

Stations in France – 77th Evacuation Hospital

Ste-Mère-Eglise, Lower Normandy – 18 July 1944 > 7 August 1944

St- Lô, Lower Normandy – 9 August 12944 > 17 August 1944

Chartres, Eure-et-Loir – 25 August 1944 > 5 September 1944

Clermont-en-Argonne, Lorraine – 14 September 1944 > 6 October 1944

The hospital’s mission for this setup was triage. The 77th would be responsible for reception and triage of First United States Army casualties, and this meant that they would proceed with examination and classification of the wounded as they were admitted, with assignment and evacuation to the proper department. The aim was to relieve other Army installations of the burden of lightly wounded casualties and funnel incoming patients; to determine each patient’s destination; and to segregate those who were unfit for immediate traveling. Those slightly ill or wounded and able to return to duty within a short time were held at the 77th Evac or sent to another nearby medical facility in Normandy. Patients with self-inflicted wounds or venereal disease were sent to special hospitals. After opening on 9 August 1944, the unit received 1,450 patients in less than 12 hours. In the 6 days that the hospital was in operation a total of 6,304 casualties were handled in triage alone, and during the same period, 599 patients were admitted to the hospital for treatment. The final number of patients would increase to 6,903. The litter bearers were mostly convalescing combat exhaustion cases from the 90th Quartermaster Battalion. After an eight-hour shift these men had blisters on their hands and were tired and aching from the heavy work. Red Cross aides brought the patients cigarettes, and chewing gum, and prepared or helped writing V-mail letters making them feel more comfortable and better. Because of the swamps in the area and the ripe fruit, mosquitoes and bees were a constant nuisance. Mosquito bars were therefore erected over the cots to protect the patients, the insects however were a constant pest descending upon the hospital and invading mess tents and kitchens. Four (4) Officers and 25 Nurses were detached to the 77th from the 50th General Hospital (activated 4 September 1942, affiliated to Seattle College, Seattle, Washington, embarked for England 29 December 1943 –ed), but as they arrived after the period of greatest activity, they were soon returned to their own unit. On 16 August, the 7th Field Hospital (landed 2 July 1944 –ed) came in to take over the work, and the same day orders were received for a move to Le Mans, France, with the advance group already leaving for the new site in the afternoon. At roughly the same time, ADSEC instructed elements of the 12th Field Hospital (landed 26 June 1944 –ed) and the 93d Medical Gas Treatment Battalion (landed 15 July 1944 –ed) to open an air evacuation facility for the Third United States Army at an airstrip near Avranches.