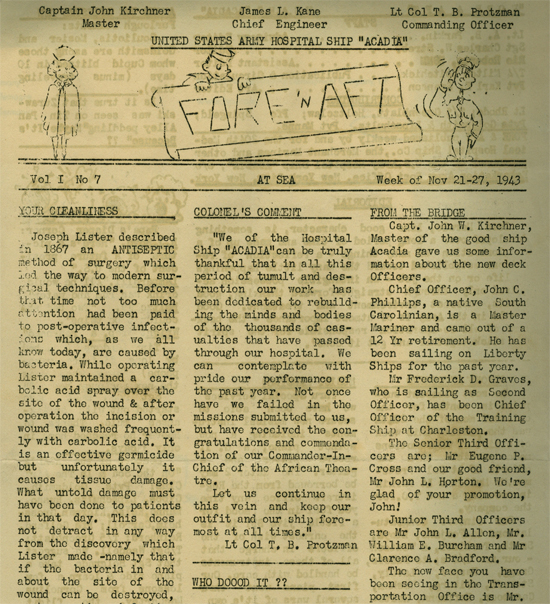

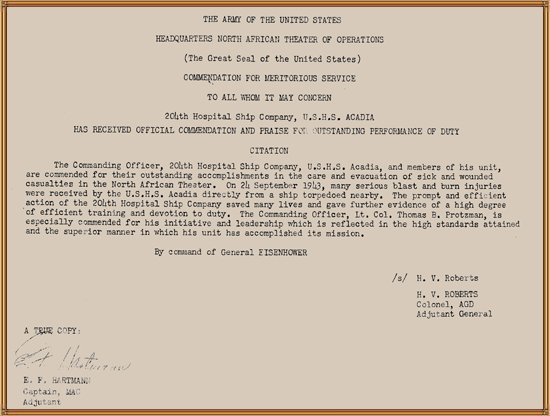

Timeline USAHS “Acadia” – Lt. Colonel Thomas B. Protzman (204th Medical Hospital Ship Company)

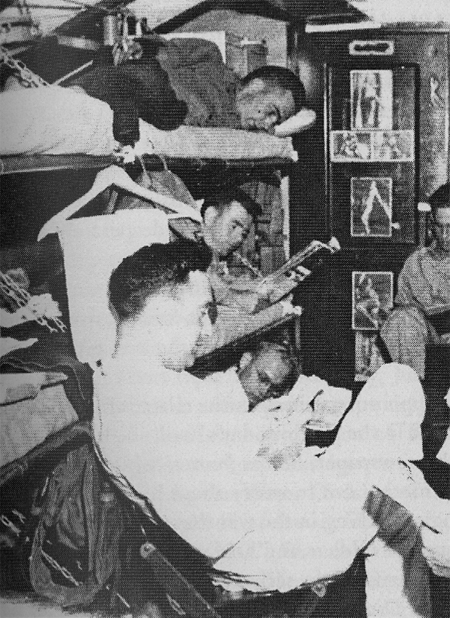

This concise Timeline is based on the “Journal” of Colonel Thomas B. Protzman, MC, Commanding Officer, United States Army Hospital Ship “Acadia”. The Journal with day-by-day entries covers the period from 11 December 1942 to 4 January 1944. We have chosen to start from June 1943, which was the FIRST voyage overseas of the “Acadia”, after its conversion to a full-fledged US Army Hospital Ship. The MRC Staff are truly indebted to Alan, an appreciative reader who donated this vintage document, a great tool which helped us prepare this ‘special’ project.

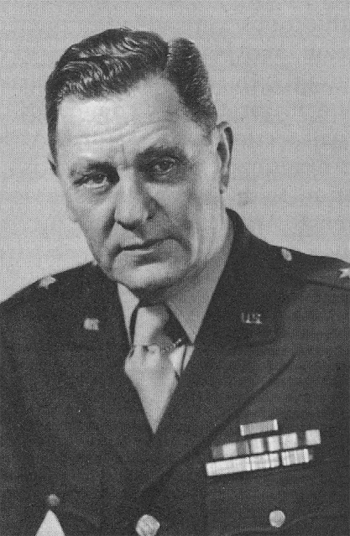

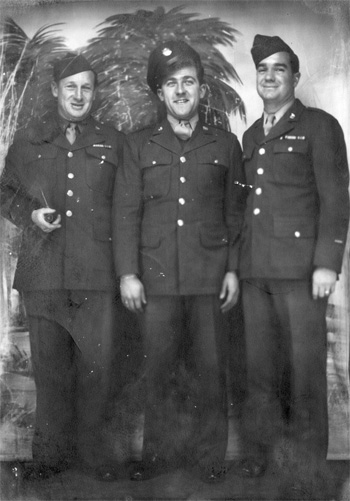

Captain Thomas B. Protzman (picture taken when serving with the 78th Infantry Division).

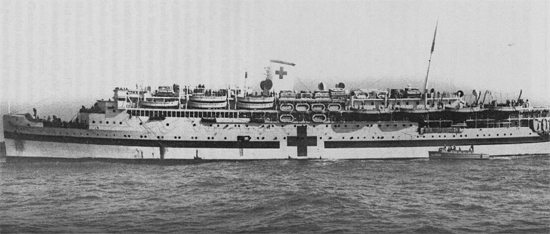

31 August 1931 > built by Newport News Shipbuilding & Drydock Company, Newport News, Virginia

29 May 1942 > conversion into a combined Army Troop Transport – Ambulance Transport Ship

1 October 1942 > personnel of the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company came on board

3 May 1943 > conversion into a US Army Hospital Ship (first one of series constructed in WW2)

5 June 1943 > maiden trip as a Hospital Ship, USAHS “Acadia”

Thursday, 3 June 1943 > Charleston, S. C., Port of Embarkation, Zone of Interior. One month ago, the USAHS “Acadia” was officially christened the FIRST US Army Hospital Ship. 125 tons of guns and armor have been removed from the top side, and the ship has been painted white all over with a broad green stripe around the middle, and numerous large red crosses in conspicuous places. The weapons have been replaced by a few automatic pistols, 5 shotguns, and 3 outmoded bolt-operated rifles. Major William V. Barney, the new Chaplain came aboard this morning. 10 more Nurses, 1 Dietitian, 2 Physiotherapists, 2 MAC Officers, 1 Sanitary Officer, 1 extra Medical Technician, and 2 American Red Cross workers, together with 33 Enlisted Men joined the already present personnel. 13 more men are expected soon. Preparations have to be finished this month, as the “Acadia” is supposed to leave for Oran, Algeria, next Saturday, 5 June. Everyone on board including the civilian crew (Merchant Marine –ed) has to be certified ‘neutral’ (for protection by the Hague Convention –ed) and carry a certificate to that effect with personal photo and fingerprints of each individual.

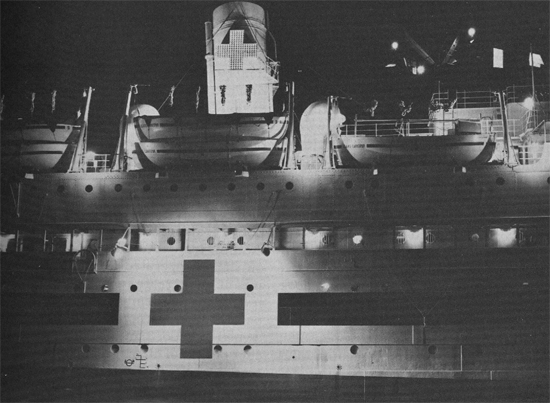

FM 55-105, WATER TRANSPORTATION: Oceangoing Vessels, dated 25 September 1944. Definition: the Hospital Ship, whether especially constructed or converted, is used mainly to return wounded and disabled military personnel to the United States (Zone of Interior) for medical treatment. The ships are owned or bare boat chartered by the Army. The Transportation Corps is responsible for their conversion, maintenance, and operation. US Army Hospital Ships are manned by civilian crews (Merchant Marine), at the direction of the Chief of Transportation, by the Ports of Embarkation to which the vessels are assigned. Hospital Ships are used in compliance with the Terms set forth in the Hague Convention of 1907. In order for vessels to obtain “neutrality” as Hospital Ships, strict adherence to these provisions must be maintained at all times. The ships are painted overall white with a horizontal green band running the length of the ship on both sides. A Red Cross is painted on the top deck and on each side of the hull and funnel and is illuminated at night. The vessel must fly both the United States flag and a White flag with a Red Cross. Each Hospital Ship must carry the following documents: Certificate of Commission designating the vessel as a United States Army Hospital Ship – Copies of the General Orders designating the vessel as a United States Army Hospital Ship – Certified True Copies of all communications from the State Department regarding notifications to and from enemy Governments in connection with the designation of the vessel as a United States Army Hospital Ship – Army Regulations 55-series (more particularly AR 55-530, governing US Army Hospital Ships), 40-series, 35-series, and any War Department circulars, bulletins, or other directives that may be released which directly pertain to the operation of United States Army Hospital Ships –ed.

Friday, 4 June 1943 > Charleston, S. C., Port of Embarkation, Zone of Interior. The 33 Enlisted Men who came aboard yesterday all need to be photographed and issued ‘neutral’ documents. Just at the last minute, we finally received 30,000 linen sheets and pillow cases. Orders have been received to sail next Saturday at 0700, but there still is no food on board.

Saturday, 5 June 1943 > Charleston, S. C., Port of Embarkation, Zone of Interior – FIRST VOYAGE OF USAHS “ACADIA”. At 0130 the boat was finally loaded and the last bed linen delivered. The Lord only knows what I’m going to do with them. We were supposed to sail at 0700, but there was a large convoy going out so we had to wait until they had cleared the lightship. At 1330 we cleared the dock and started our maiden trip as a Hospital Ship. Two Army blimps followed us until dark to ensure our safe passage through the submarine area.

Sunday, 6 June 1943 > At Sea. Chaplain W. V. Barney held his first services. At 1100 we sighted a life raft several miles away and changed our course to inspect it. There was no one on board and no identifying marks to be found.

Monday, 7 June 1943 > At Sea. Everything is running smoothly. At noon everyone took his first dose of Atabrine in lieu of Quinine of which there isn’t any. From now on we will get two doses a week until the malaria season is over.

Tuesday, 8 June 1943 > At Sea. Several of our Nurses have acute gastro-intestinal upsets from the Atabrine, accompanied with severe nausea and vomiting. My Chief Nurse is 1st Lieutenant Muriel M. Westover; she is being assisted by 2d Lieutenant Margaret Thomson. We had the first Dietitian to serve on a Hospital Ship, 2d Lieutenant Edna Stephany. Several of us are dizzy or suffer headaches. The skipper, Captain “Jack” John W. Kirchner (Merchant Marine –ed), issued the new self-inflating life vests to my outfit and the entire crew. They are rubber reinforced with cloth and wrap around the waist (they are much smaller than the kapok issue). Mine inflated four times the first day until I found I was wearing it too tightly.

Wednesday, 9 June 1943 > At Sea. The “Acadia” is making good progress averaging almost 19 knots. The weather is fine and the trip uneventful.

Thursday, 10 June 1943 > At Sea. Uneventful day. I spent most of the time in the ship’s engine room trying to make a bracelet out of 50 French Centimes pieces (brought back from a previous voyage to North Africa).

Friday, 11 June 1943 > At Sea. I finished my bracelet. The weather is fine, no events to be noted.

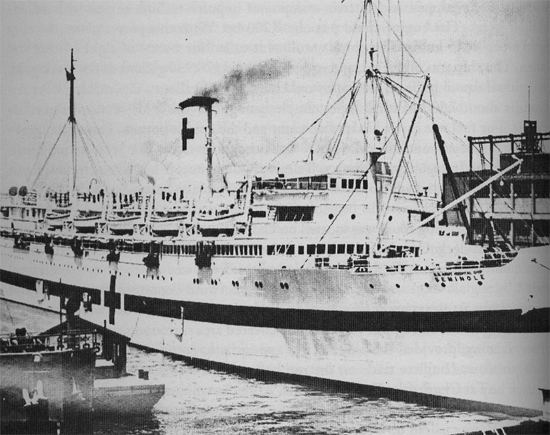

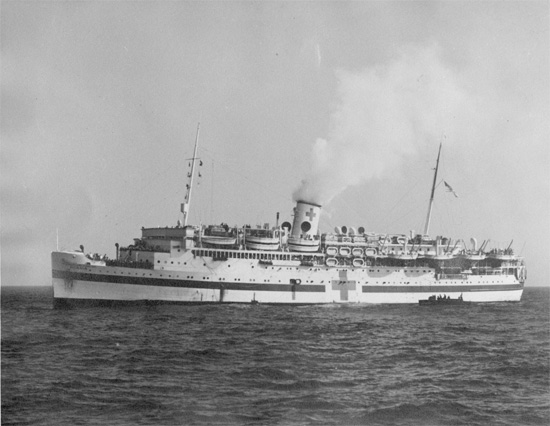

USAHS Acadia, US Army Hospital Ship (during one of its return trips to Charleston POE, South Carolina, Zone of Interior).

Saturday, 12 June 1943 > At Sea. We started the day with a grand sunrise after several days of clouds and rain. So far, we haven’t sighted a single ship. Late yesterday afternoon (11 June), we ran into a great lot of lumber of the heavy type used to shore up trucks and locomotives and a heavy oil slick. I hope it’s none of the convoy that preceded us a week ago. Mrs Lawson and Miss Ryan (ARC workers –ed), have been devoting a great deal of their time in the preparation of a minstrel show for the amusement of the patients, and tonight will be the first dress rehearsal. 20 of the 33 new boys aboard are Jews from Brooklyn.

Sunday, 13 June 1943 > Straits of Gibraltar – The Rock. I got up at 0430 this morning so as not to miss the entrance to the Straits of Gibraltar and shortly after I reached the bridge, a German submarine came up on the starboard bow and followed us for nearly a half hour but did not attempt to either hail or stop us. At about 0830 we entered the Straits and the mist was so heavy that we could scarcely see either shore, but this cleared by 0900 as we now came close to the Spanish coastline. After religious services, we all went on deck and had our first clear view of The Rock. As we passed the fortress and were heading into the Mediterranean, the British sent us a blinker message to head into the Bay and be identified. A pilot was sent aboard and we were safely guided through the minefields and anchored in Spanish waters just off the little town of La Linea, at the base of the Rock and right alongside the British Hospital Ship HMHS “Oxfordshire” (which I visited before at Mers-el-Kébir on my last voyage). I had time for a short trip into The Rock and visited the town near the airport. All the time that we were anchored Spaniards came out in small fishing boats and tried to sell some vile liquor to the sailors. The Master drove them off with the fire hose. At 1700 the “Acadia” was on her way and we hope to reach Oran, Algeria, by 0900 tomorrow.

Monday, 14 June 1943 > Algeria. Around 0700 we were in sight of the cliffs of Oran, Algeria, with the haze covered mountains in the background. 1000 hours and we have been ordered into Mers-el-Kébir and are to dock at the tip of the jetty about fourteen miles from Oran. HMHS “Oxfordshire” has also been ordered in to dock near us, so I’ll have the opportunity to renew old acquaintances. After arrival, I was told that we might have to go on to Algiers. As we came into Mers-el-Kébir a long line of assault landing barges was on its way out towards Algiers; something is getting very hot in the area as everything is being moved up into Tunisia. In spite of the fact that thousands of wounded have been shipped out of this area, there are still almost 11,000 patients in the Oran area alone, and a considerable number near the front. We saw H.M. King George VI in Oran today. Our orders are to move to Oran and load at once, for a quick return trip to Charleston POE, South Carolina, and right back again. This looks more than ever as though we will get back in time for the invasion. At 2200 the air raid alarm was sounded. I was invited to review the 250-bed 64th Station Hospital at Sidi-bel-Abbès, tomorrow afternoon.

other US Army Hospitals in the Oran area, Algeria, during the period

151st Station Hospital (250 beds, La Sénia, 25 November 1942 > 31 May 1944)

7th Station Hospital (750 beds, Oran, 1 December 1942 > 31 July 1944)

180th Station Hospital (250 beds, Ste. Barbe-du-Tlélat, 7 December 1942 > 30 September 1943)

64th Station Hospital (250 beds, Sidi-bel-Abbès, 28 December 1942 > 31 May 1944)

21st General Hospital (1000 beds, Sidi-bou-Hanifia, 29 December 1942 > 30 November 1943)

12th General Hospital (1000 beds, Ain-et-Turk, 14 January 1943 > 3 December 1943)

2d Convalescent Hospital (3000 beds, Bouisseville, 28 February 1943 > 31 May 1944)

40th Station Hospital (500 beds, Mostaganem, 4 March 1943 > 15 January 1944)

91st Evacuation Hospital (400 beds, Mostaganem, 2 May 1943 > 27 June 1943)

94th Evacuation Hospital (400 beds, Perrégaux, 22 May 1943 > 29 August 1943)

16th Evacuation Hospital (750 beds, Ste. Barbe-du-Tlélat, 23 May 1943 > 8 August 1943)

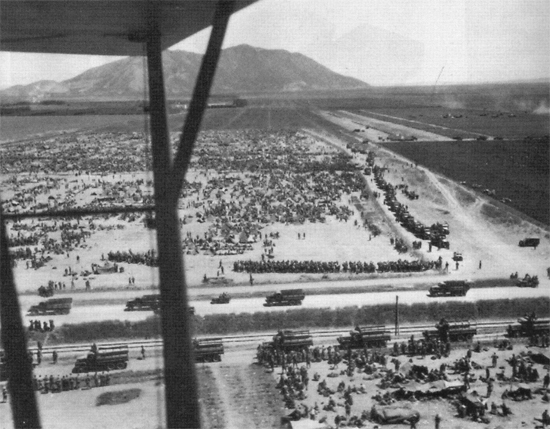

Tuesday, 15 June 1943 > Algeria. At 0200 several of us went down the dock about a mile to watch the unloading of several thousand German PWs; they were all under 25, a great percentage of them paratroops, in excellent physical condition, and the majority of them were singing and whistling. These boys will be marched to the PW enclosures for the night and paraded through the city in the morning. Afterwards, they will be transported to the Zone of Interior on a next convoy. Shortly after we started to load the wounded, a fire broke out in an ammunition dump of 75mm shells alongside the ship and we had considerable excitement for the time it took to control the blaze. All the ship’s fire lines were necessary to get the situation under control. Just a careless cigarette caused all the trouble and might have sunk our boat. At 1430 we took off in four passenger cars and one jeep for Sidi-bel-Abbès, the home of the French Foreign Legion, to inspect and review the 64th Station Hospital, they won the Army’s “E” award for having been the best Hospital in the area for the past month. After our visit we got invited to a GI banquet with French wine. The Nurses wore evening gowns fashioned from cloth they were able to buy from the natives. In all we had a splendid time and drove back early in the morning with blackout lights. When we reached the “Acadia”, nearly 500 patients had been loaded and the rest were expected later the next morning (Wednesday).

Wednesday, 16 June 1943 > Algeria. This will be the quickest turn around. We are to leave at 1700 today. Everyone is pleased as lots of us have seen enough of Oran. We passed the PW enclosure on the way to the base and saw several thousand German prisoners in a large wired-in field, totally bare of vegetation, well covered with rocks and hot as the hobs of hell. I felt sorry for the poor devils, but I guess our boys aren’t being treated any better! Chaplain W. V. Barney has been doing a great job with the wounded and the men seem to like him; the American Red Cross workers, Mrs Lawson and Miss Ryan, have been doing a splendid piece of work in making the boys feel comfortable, they have distributed small comfort bags to each patient, containing many little things that Uncle Sam doesn’t furnish. One of the most desirable articles and giving the most comfort is a pair of slippers. The girls placed small libraries in each ward, and provided a collection of newspapers from all the important towns and cities in the United States. They also brought a ‘coke’ for each patient. At 1700 sharp our boat left the pier and we started on our return trip. The sea is pretty rough and the wind is blowing so hard I can hardly hold my camera steady. We should pass The Rock of Gibraltar about 0600 in the morning and be well out in the Atlantic by the afternoon. We travel alone and our boat will be routed the shortest way home.

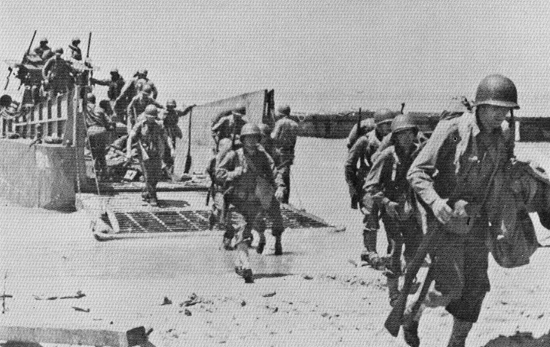

Operation “Torch”, the Allied Invasion of North Africa (8 November 1942).

Thursday, 17 June 1943 > At Sea. The sea is pretty rough and most of the ambulatory cases are getting seasick. Some of the boys have started to gamble openly in rather large games so I issued a stop order on the playing and appointed one of my staff as Provost Marshal to carry out the job.

Friday, 18 June 1943 > At Sea. The last belligerent nation (Japan) has been notified of the new status of the “Acadia”, now a non-belligerent vessel protected by the 1907 Hague Convention. We have been doing approximately 19 knots all day even though the weather continues to be rather rough. The day was uneventful until the evening when during a jam session 3 of the NP cases began to fight and we had lots of trouble getting them under control and into restraining sheets. This was only possible after they had been given large doses of Sodium Amytol and Paraldehyde. One of the merchant mariners had sold them some liquor and that is what started the fight. We have 263 psycho cases on board and no adequate place to hold them (there are only two padded cells in the stern of the ship). One patient Officer admitted paying as much as $ 100.00 for a quart of rye whiskey, but couldn’t put the finger on the sailor when I had them all paraded for investigation.

Saturday, 19 June 1943 > At Sea. At 0445 I was called to the bridge as a distress flare had been seen several miles away. Only one was seen and we were unable to get a bearing. The Azores are only about 60 miles away, so maybe the boat will reach there. Everything is going fine on board; the ARC workers and the Physiotherapists made the boys more comfortable and kept them occupied. One poor guy in my surgical ward had both his eyes shot away and the Red Cross girls have been wonderful in their efforts to bring up his spirits and to give him some hope for the future. In another ward, I discovered a boy who had been an accordionist in a famous dance orchestra stateside. He has severe shrapnel wounds in both hands sustained at Bizerte, Tunisia. Only he and his Captain came out alive. He was sitting alone in a corner of the ward crying; the only thing he knew was music, his only means of support, and his fingers were all stiff and sore. One of the Physiotherapists has baked and massaged his fingers and hands and today, the patient was able to play a tune on the ship’s accordion. In the isolation ward, there’s a young colored boy dying of TB; he was almost moribund when they brought him on board, and now he just wants to see home before he dies, but I don’t think he will. Today, 2 young doughboys who had been classmates in school several years ago, found each other at our movie theater, and they really had a reunion!

Sunday, 20 June 1943 > At Sea. 0730 this morning the little colored boy lost his fight and the chance to see home again. Of the 800 patients we have on board, only 150 have service records. Our Chaplain did a good job this morning; his sermons are short and snappy but have a lot of meat in them.

Monday, 21 June 1943 > At Sea. The little merchant mariner (manic depressive) has just finished ripping his sixth bathrobe into shreds. None of the sedatives seem to help control him. The NP case who started the fight is still in restraining sheets and will probably remain so for the rest of the voyage. The whiskey certainly did a tremendous amount of damage to his mental system; he has been raving wild ever since and threatens to kill us all if he ever gets out. There are 2 men on guard at his bed all the time. At about 1730 we sighted a large iceberg, several times the size of this ship. The barometer has been dropping all evening, but at 2130 the Captain called me and said to secure all patients as we were running into a hurricane. It effectively hit us about 2200 and the ship really did some stunts. We just kept going headway into the storm at about 3 knots; none of us got much sleep, but we managed to get through all right without any serious damage. We will probably be a day late for arrival.

Tuesday, 22 June 1943 > At Sea. The sea is considerably calmer and we are making about 6 knots but the percentage of seasickness has risen to appalling proportions. As we depend on ambulatory patients to help with cleaning, dishwashing and guard duty, the ship will just have to get and stay dirty and go without guards. If nothing special happens we should be in by next Friday and I certainly hope we aren’t kept out in the harbor as last time.

Wednesday, 23 June 1943 > At Sea. We are pretty well out of the storm area and there is much less sickness, but we have lost a whole day because of it and won’t arrive until Friday morning.

Thursday, 24 June 1943 > At Sea. Clear calm day with a bright sun. A great many of our patients have been on deck long before daylight just in the excitement of being only a few hundred miles from home. Even our mental patients are better, yet the poor devils won’t get the freedom we give them here. We can afford to be more generous at sea as they have no place to escape to. The boy with the accordion is playing quite well now and his face just shines with hope. The little merchant mariner’s situation improved and we allowed him out of his dell for the first time yesterday.

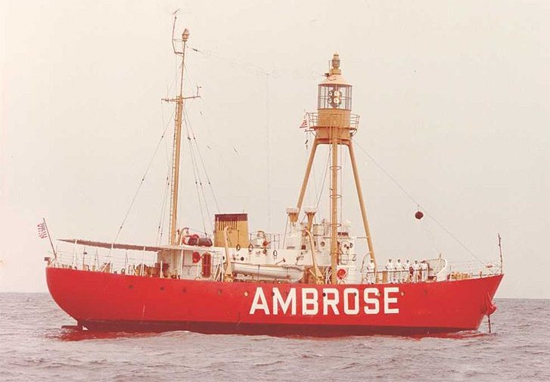

Friday, 25 June 1943 > New York, N.Y., Port of Embarkation, Zone of Interior. We didn’t reach “Ambrose Light” (Ambrose Lightship WAL 533, navigational light beacon marking Ambrose Channel, one of the main shipping channels to New York Harbor –ed) until 1030 and will not dock until well in the afternoon. The skipper called the Port Authority and we are to dock at pier 15 for debarkation. There’s a band playing and what looks like a special delegation is on site to meet us. 1430, we have just got rid of the last General and the last Congressman and Senator. It amuses me a great deal as we have been doing the same kind of work for the past 7 months (the “Acadia” was an ‘Ambulance Transport’ then –ed) under much greater handicaps and now that we are the FIRST white-painted (Hospital) ship in the United States Army, we become suddenly important and the powers that be, must come to visit, inspect, and criticize. Major General Norman T. Kirk (The Surgeon General –ed), with his entire staff was there. He made a quick tour of the ship and seemed satisfied. Major General Charles P. Gross (Chief of Transportation, Army Service Forces –ed), was quite critical of my Nurses because I had them dressed in slacks. He also thought my EM were not dressed properly; but when I advised him that he was looking at my NP patients instead of at my soldiers he withdrew his statement. I also told him that we had just come through a two-day hurricane and were more concerned with the care of our patients than with the preparation of a parade. Nevertheless, we will have to put on a show for these people every time we arrive in port until the novelty of this all wears off. The ship’s Master and I had to greet the assembly with speeches and pose for photographs that will never be published, as we are still running in complete radio silence, and our mission seems to be a deep secret.

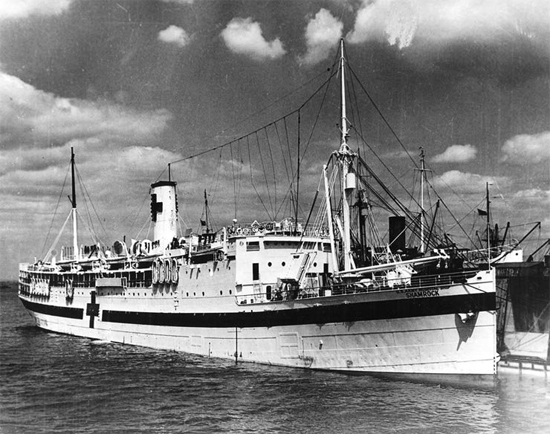

I later heard that we’re going to make a quick turn around and will leave again Sunday or Monday. Something very hot must be cooking and we must be badly needed. The USAHS “Seminole”, the SECOND Army Hospital Ship (first: “Acadia”, second: “Seminole”, third: “Shamrock” –ed) sailed for North Africa on Monday of this week (the “Seminole” would serve exclusively in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean –ed). When I inspected her the day we sailed, the whole ship had been gutted, and at the time I felt that she couldn’t possibly be finished for at least a couple of months. Yet, Colonel Holder (Office of The Surgeon General –ed) had produced another miracle and we will now have 2 Hospital Ships in the combat zone. If the new CO runs into the storm we just came through, he will get a baptism of a very unpleasant character. Its capacity is about 450 wounded.

While the Surgeon General was visiting, we clarified the life saving situation and will do as the British – carry our full capacity of absolute litter cases. This means of course that in the event of a torpedo or mine, or another disaster, the badly wounded cases will have to take that extra chance. They are given the protection of the Geneva Convention and that will have to suffice as it is imperative that those totally disabled with wounds and injuries be removed from the Theater of Operations as soon as possible.

The “Ambrose” Lightship, navigation light beacon, marking one of the channels into New York harbor. Picture taken in WW2.

Saturday, 26 June 1943 > New York, N.Y., Port of Embarkation, Zone of Interior. We were unloaded by about 2230 last night. Halloran General Hospital (Willowbrook, Staten Island, N.Y., designated General Hospital by WDGO # 53, dated 14 October 1942 –ed) held us up as they weren’t able to take the patients as fast as we could debark them. A less complicated system of receiving will have to be instituted. These are all clean cases so far as contagion is concerned. We are losing Mrs Lawson and Miss Ryan (ARC workers) who did such splendid work with our patients. Their replacements will be on the ship tonight. I have great confidence in my Officers and Enlisted Men and have very little trepidation as to how they will function when the ‘great’ moment arrives. We all wish to be with the invasion forces (Sicily Invasion, 10 July 1943 –ed), and I sincerely hope we can reach the area in time. Heavy bombing of the enemy is just a softening-up process to make the invasion less difficult and less costly. Our time is so limited and there are so many supplies that have to be placed on board, meaning very few of us will get much sleep before we sail. We are to carry an extra supply of medical and surgical equipment for ourselves and also for the “Seminole”. The day before we docked one of our Medical Officers gave me this poem which we mimeographed and distributed to our men. It’s his impression of “Acadia” as he saw her at anchor in the Bay of Oran…

USAHS “Acadia.”

A White Ship

She Lies at Anchor in the Bay

A Big White Ship looking Gay

Amidst her Sister Ships of Gray

A Big Red Cross upon her Sides

Marks her Mission as She Rides

Upon the Water and the Tides

Within her Decks are Those in White

Who Heal our Wounds Throughout the Night

And Give Those Strength Who Fought the Fight

(by Walter D. Higgens, Captain, MC, US Army, 6/24/43)

Sunday, 27 June 1943 > New York, N.Y., Port of Embarkation, Zone of Interior. The whole day was spent with the powers that be, of the Port and Washington. We now have definite orders to sail tomorrow night without fail. We are to take part in the attack by going in with the Allied invasion forces. Time and place are a deep secret. This next trip, I hope, will make favorable history for the Medical Corps, as a new policy has been instituted; indeed, this is the first time in the history of the United States, that an MC Officer has been given complete command of the ship and the Hospital. Before, a line Officer was given command of the ship, and a Medical Officer command of the Hospital unit, subservient to the line Officer. I pray the Gods that luck be with me, for on my actions depends the future policy of the War Department concerning the powers of the Medical Department in all future ventures of this magnitude. Though we have never been in actual battle, I feel and am confident that my outfit will come through as they have in previous emergencies. I had to keep all Officers, Nurses, and Enlisted personnel on the boat all day as we weren’t sure just when the sailing time would be. When I returned at 1800, I gave the men till midnight and the Officers and Nurses till 0800 the next morning. Practically all the Officers, the Captain and myself went to “Gloucester House” on 51st Street and had lobster for supper. We then returned to the boat and began to check on loading the extra supplies.

Monday, 28 June 1943 > At Sea – SECOND VOYAGE OF USAHS “ACADIA”. Most of the day was spent in last minute efforts to get the extra supplies we need so badly and a few repairs. We only have food enough for three months so there’s a possibility that we may return by then. I was back at the “Acadia” by 0300 and we were just about ready to pull out early when Major General Homer M. Groninger (Commanding Officer, New York Port of Embarkation –ed) ordered me back to Headquarters for a final conference. There were no cars so I commandeered a ¼-ton truck and made the trip. All the General wanted to know was whether I was sure that our mission could be carried out successfully. While I was in his office, Major General N. T. Kirk, called from Washington with some last minute instructions and also with the admonition to put our expensive laundry (bed sheets) to work. We finally left the pier at 0535, only 35 minutes late. We then spent several hours sailing around “Ambrose Light” adjusting our radio direction finder and didn’t leave the channel until 0930 hours.

Major General Norman T. KIRK, US Army Surgeon General (1 June 1943 > 31 May 1947).

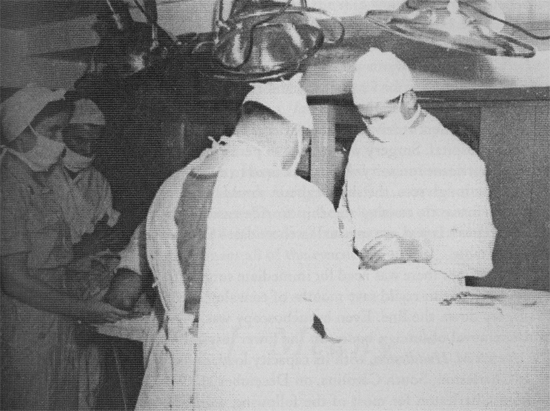

Tuesday, 29 June 1943 > At Sea. It’s a great relief to get out into the ocean away from the heat of New York. The sea is extremely rough and one of the new Nurses is already in trouble. Our trip from now on will be jammed full of activity as we now have a definite objective and only a short time in which to renew our minds on the things that will have to be done on short notice. In the morning we held a meeting with the Officers and the Nurses during which we planned an instruction program for everyone on the ship. Operating teams were formed, of which there will be three; shock teams of Enlisted Men and Nurses for plasma and blood transfusions were established. The EM will handle the general nursing while the Nurses will be stepped up to do the immediate first aid work, thus permitting the doctors to act on the surgical or burn teams. Our Chaplain will take over supervision of loading of the wounded by means of metal “Stokes” litters. The latter task may be very difficult as the operation may have to be accomplished from the water or from lighters or landing craft and if there is any sea at all the job will be hazardous! The ARC workers, Physiotherapists and Dietitian will attend to the feeding of hot drinks and sandwiches to those cases able to take nourishment and to assist the shock teams. For 8 hours each day, everyone will be making and preparing surgical dressings and supplies. For the next 6 hours, classes will be given, a kind of general refresher course. Up to this time, discipline on board has been rather slack. The trip started with a rigid course for all and both our men and women are taking it with their chins up and without complaints.

Wednesday, 30 June 1943 > At Sea. We have been fighting a heavy sea ever since the voyage started and this morning the waves even rolled over ‘C’ deck and washed down one of the open companionways giving the whole boat a drenching inside. It almost took the whole morning to mop up the water. Instructions were given in gas mask use. Armament on board only consists of 5 shotguns and 3 bolt-action rifles. Officers received daily instruction in the use of .45 caliber automatic pistols. None of these are to be used against the enemy (as per Geneva Convention regulations –ed), but for internal security and self defense if necessary. The Nurses prepared several large packing boxes filled with new dressings to be sterilized.

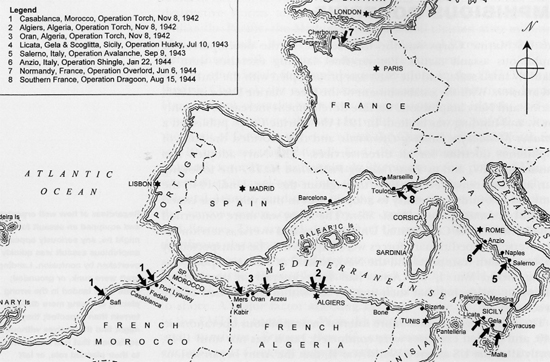

Major Allied Operations – Mediterranean Theater

Operation “Torch” – Allied Invasion of Northwest Africa, 8 November 1942

Operation “Husky” – Allied Invasion of Sicily, 10 July 1943

Operation “Avalanche” – Allied Landings at Salerno, 9 September 1943

Operation “Shingle” – Allied Landings at Anzio, 22 January 1944

Thursday, 1 July 1943 > At Sea. I forget to say that I have a new orderly, Pierre. This boy is a real find and has made my room so orderly that I’m almost afraid to use it. He was formerly a secretary/valet for a N.Y. Senator and just before joining the Army worked for the Duke and Duchess of Windsor (ex-King Edward VIII and Mrs. Wallis Simpson –ed). Early this afternoon a B-24 Liberator bomber flew around us for some time. Since our Chaplain is in charge of loading patients he and the Captain have rigged up 6 slings with block and tackle to lift patients out of the water or from small craft. This is something we may not need (as the inevitable gas mask drills), but could come in mighty handy if we can’t load through the ports.

Friday, 2 July 1943 > At Sea. The ship is in excellent shape and the men are attending classes all through the day. Tonight we will show our first movie. As I went on deck this morning, the Nurses that were off duty were there folding gauze in their bathing suits. My rifle and shotgun squad have reached perfection in drill with their weapons, and if the weather permits I will start them on target practice.

Saturday, 3 July 1943 > At Sea. Fog all night with the ship’s whistle blowing away and our boat plugging along at only 4 knots. We ran into a fairly large area of slush ice, though we selected this southern route to escape fog and icebergs. Our orders are to be in Gibraltar by 7 July, where we are to receive further instructions, so we’re doing 21 knots now to make up for the lost time.

Sunday, 4 July 1943 > At Sea. At noon we were only 800 miles from Gibraltar. We will now have to slow down as we’re ahead of our schedule in spite of the weather. Rifle and shotgun practice were given this afternoon. The ARC workers unpacked a couple of book cases and as the choice wasn’t really what we needed (mostly children’s books such as; King Arthur of the Round Table, Little Lord Fauntleroy, and the series The Modern Farmer, etc) we gave them all to Father Neptune. The Chaplain had a great turn out this morning.

Monday 5 July 1943 > At Sea. Uneventful day. Another B-24 four-engined Liberator bomber flew over our ship this morning and then returned in the direction of Gibraltar. We are about 600 miles from our RV point and have slowed our speed considerably.

Tuesday, 6 July 1943 > At Sea. We are now starting to make circles in order not to hit the Straits of Gibraltar before daylight. Someone of the crew forgot to shut off the water in one of the utility rooms, flooding one of the decks. The Master-at-arms is supposed to patrol the ship but has been sleeping, Captain “Jack” instituted a time clock that all men will have to punch at different locations all over the ship. The crew is mad and want to quit, but it won’t do them any good. Another British Liberator aircraft flew over. Nurses and Enlisted Men have been working like hell and now have a great supply of surgical dressings, ready and sterilized. My outfit is now ready for any emergency!

Wednesday, 7 July 1943 > Gibraltar, The Rock. 0600 hours, we are splitting a large empty convoy going back to the States. It’s quite foggy and we couldn’t see where we were, near or far from the other ships, until we were right on top of them and couldn’t get out. Fortunately no damage was done, and we hit the Straits around 0700. As we neared The Rock the haze cleared rapidly, and we saw several aircraft in the sky, and a harbor full of ships. We anchored at 1100 near the USAHS “Seminole” and three British Hospital Ships. It looks like the real thing now, and all preparations won’t be in vain. The Port Commander left us at noon after giving us instructions to move up to Algiers the day after tomorrow. On talking with some of the British Officers, I find that the plan is to sandwich us between two British ships so that we can have the benefit of their previous battle experience. From the looks of things I would say the invasion will start within the next few days. We had to arm our guards with shotguns and parade them around the decks of the “Acadia” as some of the locals kept coming too close with their small boats, trying to sell bad liquor to the boys; the guns aren’t loaded, but do the trick. We are in Spanish waters and these men have the perfect right to go where they please, only some of them have been planting time bombs and four ships were sunk last month (by Italian frogmen –ed), so everyone has got to be more careful. 2000 hours and we just finished taking supplies over to the “Seminole”. These poor devils are in a very bad situation. Their vessel was fitted out so rapidly (May-June 1943 –ed) that they have no sufficient supplies and a great deal of their equipment hasn’t been installed. When their boat first sailed from New York, they were to go to Oran, Algeria, and pick up a load of wounded and come right back. Now they have been ordered to an invasion point and they aren’t ready, through no fault of their own. They left us in the morning with two of the British ships and headed for Philippeville, another port in Algeria. I took my Officer over to their boat and we gave them all the help and advice we could in such a short time. Most of these lads are from Texas, and were only in New York two weeks before they sailed.

Partial aerial view of “The Rock” – Gibraltar, showing airport runway, harbor, and bay. Picture taken in WW2.

(during World War 2, Gibraltar played a vital role in both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Theaters, as it controlled virtually all naval traffic in and out of the Mediterranean region. It was there that General Dwight D. Eisenhower coordinated “Operation Torch”. Following the successful completion of the campaign in North Africa culminating with the surrender of Italy in 1943, the “Rock” continued to serve as an Allied base operating dry docks and supply depots for the convoy routes running through the Mediterranean until VE-Day –ed).

Thursday, 8 July 1943 > Gibraltar, The Rock. 0200 in the morning, several depth charges went off and woke me up. At first I thought we were in convoy again but it was only the British patrol boat dropping charges in the bay to discourage any saboteurs or infiltrators. I went on deck and admired the other Hospital Ships with their lights on. Later in the morning, before daylight, the 3 British ships left, and the “Seminole” will leave about 1400 this afternoon. They are bound for Bône, Algeria, and not Philippeville. The Captain and I were trying to get more oil for our ship and we spent a lot of time trying to unroll British red tape; we finally got the oil after seeing the American Consul. We stopped to have dinner at the “Hotel Bristol” and paid $ 2.00 per person for some lousy food and warm beer. While we were on the way, the British Navy was putting on a ceremony for the body of Polish Prime Minister Wladyslaw E. Sikorski that was being repatriated to the United Kingdom (Polish Prime Minister, 20 May 1881 – 4 July 1943, killed in a plane crash -ed). The Liberator bomber was too heavy and failed to rise, crashing in the sea and killing everyone except the pilot. We sent Lt. Colonel C. W. Salley (CO > USAHS “Seminole” -ed) and Chief Nurse Catherine Ambry some more supplies today. He hasn’t been able to get his motor boat fixed. All his life boats are hand-operated and neither the merchant marine crew nor his medical complement know how to operate them. I certainly hope he won’t get into serious action. If we stop any length of time in Algiers, I’ll go and see General Smith and see if his orders cannot be changed. We leave Gibraltar at noon tomorrow and should be in Algiers by 1100 next Saturday.

Picture of General Władysław E. Sikorski (1881-1943), killed in an airplane crash 4 July 1943 in Gibraltar.

Friday, 9 July 1943 > Gibraltar, The Rock. A lot of depth charges were dropped last night but the bay looks serene this morning. We put on six extra guards to patrol the ship and watch out for divers or frogmen. The water is so clear one can easily see the bottom and we have the advantage over the other boats that our side lights are on and the visibility is excellent. We pulled up anchor at noon and are now well out in the Mediterranean Sea with excellent weather. In the morning we will hold several emergency drills to make sure everything will work smoothly and by tomorrow night we should know definitely where we are going.

Saturday, 10 July 1943 > Algeria. We started the day by listening to the news reports of the assault against Sicily and all hope our boys can hold their beachhead. Our emergency drills came off with only a few mistakes; and we will hold them daily from now on until we move up nearer the field of battle. 1030, we just passed a large convoy of Liberty ships going into the Mediterranean loaded with troops and supplies. During the drill this morning we pulled a surprise gas attack and only a few of the Nurses had forgotten their masks. I did this for a very definite reason – my outfit doesn’t know, but some of the ships at Gibraltar were carrying cargoes of poison gas to the front just in case Germany or Italy might start using it. We all are afraid that they will when the going gets tough. At 1500 hours we were anchored well in Algiers harbor away from the city, and the sea is too rough to attempt to go ashore by small boat. While at anchor a fully-loaded convoy left for the east, crossing the one we passed earlier in the day. There were thirty-seven ships in this one. The harbor is full of troop and cargo ships fully loaded and ready to move where needed. We heard there were 1,200 ships during the assault against Sicily. 1600 hours and another convoy comes in. Because of the ongoing sea traffic, we will remain offshore and out in the ocean till tomorrow. The harbor is still protected by barrage balloons. The last enemy air raid took place on 15 June and I believe the Krauts have too much other business to attend than to bother us tonight, though the moon is very bright.

other US Army Hospitals in the Algiers area, Algeria, during the period

29th Station Hospital (250 beds, Algiers, 30 January 1943 > 25 August 1944)

79th Station Hospital (500 beds, Algiers, 17 June 1943 > 30 June 1944)

Sunday, 11 July 1943 > Algeria. Early this morning we contacted USS “Vulcan”, AR-5, one of our Navy repair ships (1941-1991, served in the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Pacific –ed) and their CO, Captain Richard Tuggle, came over and took several of us back to his ship where we could contact our Headquarters by phone. He has also sent us repair men to fix our PA system and our motor lifeboat. I first called General Smith and found out he was still at the front; next I called Brigadier General Frederick A. Blesse, (Surgeon NATOUSA –ed), and learned he was also at the front. My next best bet was to try and contact Colonel Earle G. Standlee, (Deputy Surgeon NATOUSA –ed), who promised to come right over and inspect the ship. Colonel E. G. Standlee and Lt. Colonel B. Manly, both of the Surgeon’s Office, indeed gave us an inspection we will all long remember. I’m terribly proud of my outfit, the 204th Medical Hospital Ship Company, as they came through in splendid style from the lowest buck private on guard at the gangway to the highest Officer. While on the “Vulcan”, we talked to the first casualties of the Invasion (Operation “Husky“ -ed). They were on a freighter that had recently unloaded a cargo of mustard gas at Bizerte, Tunisia, and were returning to Oran, Algeria, when an enemy sub torpedoed them. The ship capsized and sank, and only a few crew members were saved. After my first inspection, I returned to shore to report to the British Admiralty to see whether they had any orders for the ship. At the time the British had overall control of all shipping in the Mediterranean and also of the port of Algiers. I no sooner finished there when I was blinked back onto the ship for another inspection. Brigadier General E. L. Ford, (Chief of Staff, NATOUSA, activated 4 February 1943 –ed) and some of his Officers gave us another going over and couldn’t find anything wrong except that we were not to use the port water for our laundry, as it was much too scarce. At 1700 I tried calling General Smith again and he answered the phone; he said he was greatly pleased with the results of the invasion and that we had lost only 10% of the men in the assault wave. I learned that the “Acadia” is slated to go into action with 11 British Hospital Ships and take on patients from the water off the shores of Sicily. We are now standing by with steam waiting for our orders. We are allowing the French citizens here in Algiers, 10 gallons of gas a week as a good neighbor policy.

Monday, 12 July 1943 > Algeria. I gave shore leave to all our personnel until the 2200 curfew and they all returned in fairly good condition. There will be no more leaves from now. We spent the morning getting the ship in order, just in case anybody else cared to inspect it, and sure enough just as we were sitting down to dinner, Major General Ernest M. Cowell, Director, British Medical Services, responsible for the administration of all medical activities in NATOUSA, popped in and asked to see me. I took him through a quick tour of the ship, but he was only interested in seeing the operating rooms, my surgical teams, and wanted to know if we were prepared to take wounded from the water. One of his first questions was; “how many Nurses have you got and do you want to take them off the boat before going into action?” I put the question to the girls themselves, and not one of them wanted to quit! He was pleased. I told him of the reprimand I had received from Major General C. P. Gross for putting my Nurses in slacks, and he laughed and said: “You know, the Queen did not approve of my putting British Nurses in trousers while in action, but I still keep on doing it as they are the only clothes they can work in properly.” He advised against the use of too many sulfonamides in the burn cases, and due to the shortage of water on Sicily the wounded would be brought in dehydrated and should be given great quantities of water to dilute the sulfonamides they had taken by mouth on the battlefield. A bad form of malaria is also cropping up and a great deal of diarrhea. All these will cause complications with battle wounds. This man is a great General! Late in the afternoon I went ashore to collect some new movie films from the USO and saw several thousand Italian PWs being unloaded from trains directly onto boats. They seemed in excellent condition and were all burned by the sun from the long desert warfare, but seemed to have but little clothing. We spoke to some of the French guards and they felt quite bitter that the prisoners were getting more to eat than the guards themselves.

Tuesday, 13 July 1943 > Algeria. Last night the British Hospital Ship HMHS “Talamba” was sunk with 800 wounded on board in retaliation for our sinking of one of the Italian Hospital Ships two days ago. The “Talamba” was fully lighted and was sunk by a dive bomber about three miles off the Sicilian coast. I talked to the British aviator who sank the enemy Hospital Ship and he explained that he was so high that it was impossible to distinguish any ‘special’ markings. His orders were to sink all ships in a certain sealane and that is what he precisely did, not knowing that it was a Hague-protected vessel. At 0800 we borrowed a motor launch and boarded the British Hospital Ship HMHS “Amarapoora” (400 beds) to see what tackle they were using to bring the patients over the side. They were very gracious and demonstrated the system, but their method was inferior to ours so there’s to be no adaptation. At noon, Colonel Edgar E. Hume (US Army) and Colonel D. Gordon Cheyne (Royal British Army) had dinner with me on our boat. These men are from AMGOT (Allied Military Government of Occupied Territory –ed) and will soon take over Civilian Government in Sicily. The fighting is going on so rapidly in Sicily and so few of our doughs are being wounded, that we probably won’t get up to the front at all. I hate to think of lying out in this harbor (Algiers) with nothing to do. My boys will go nuts, as none of us are allowed off the boat, just waiting several miles from shore. In the afternoon, my friend Major General Ernest M. Cowell of Her Majesty’s Forces sent his crack group of epidemiologists over to give a talk on malaria. One of the speakers, Colonel Schauff (malaria specialist), feels that 200 out of every 1,000 soldiers will probably contract malaria unless the program to use Atabrine is rigidly adhered to. Right now, we know that malaria and other diseases are killing more Japs in the marshes and jungles of Guadalcanal than our soldiers do. Around 2000 a large convoy of troop transports is coming into the bay escorted by battleships and destroyers. They drop anchor just outside the harbor and will probably supplement the invasion forces or relieve some of the assault troops on Sicily. I sincerely hope we go out with them. The “King George V” (14-in gun battleship, part of H Force in Operation “Husky” –ed) is right near us and must be the largest battleship in the world. We met some of her Officers and they told us that the invasion of Sicily was a complete surprise to the Axis forces as not a single enemy reconnaissance plane was permitted to return for 10 days before the attack. They were all shot down. I collected some more film for my camera and picked up a few German war souvenirs.

Operation “Husky”, the Allied Invasion of Sicily (10 July 1943).

Wednesday, 14 July 1943 > Algeria. Bastille Day in Algiers. At 0700 this morning, a landing craft came to our gangway and we took on 8 wounded British soldiers on board (5 litter cases and 3 ambulatory patients). Some of them were paratroopers and glider riders who hit Syracuse, Sicily. They were pretty badly shot up but happy to get on a Hospital Ship. My girls peppered and spoiled them. 1800 and we have been ordered to stand out to sea and anchor. USAHS “Seminole” has already returned to Bône, Algeria. She came in yesterday with casual wounded men from Bizerte, Tunisia. Just as we anchored about five miles from the port area, a Navy boat drew alongside and signaled us to prepare to take on 600 wounded, either still tonight, or early in the morning. We learned that a fleet of thirty ships was returning from Sicily with casualties and that we are to take them to Oran. As we had to return to port for loading, everyone was disappointed since we all could have had a day on shore. Some of the frustration was eased by the gift of a four-inch telescopic lens for my Leica camera, recovered from a downed German plane. That will allow me to take some distance shots.

Thursday, 15 July 1943 > Algeria. It is 0530 and we are returning to dock to take on patients. We pulled in about 0600 to take on the wounded. Major W. V. Barney, our Chaplain did a splendid job. At one time, he and his men loaded 11 patients over the sides in three minutes with a single tackle he had devised himself. While we were in the midst of the loading (using “Stokes” litters), Brigadier General F. A. Blesse came aboard and got a kick out of the unusual sight of a Chaplain doing something entirely different from preaching. The General told me that during the original assault only 680 men were wounded and that not a single enemy plane was seen. The ones we are taking on now are some casualties of that attack. We are to take on the cases from ships here, fill up the boat, go to Oran, unload, and await orders there. Later, a great many wounded were brought from the docked ships by British and American ambulances and all were then carried on board by stretcher details composed entirely of Italian prisoners. These lads did a splendid job and were as happy as anyone could be in captivity. I have many Italian boys in my outfit so the PWs thought they were home on an Italian ship; they wanted to stay and go to America. Among the many patients, we have 18 Italians, several cases of malaria, and some with dengue fever. Most of the badly burned cases are from a boat that suffered a near miss that ignited gasoline in the hold, trapping them in the fire! At one time while we were loading, an order came for us to leave the dock and put to sea. As there were several landing barges of patients waiting, we started speeding up the loading process. As soon as the news reached the wounded implying that some of them might be left behind in Algiers, a number of litter cases got up under their own power and climbed the ladders onto the ship, in casts, with only one leg, and some badly wounded. They helped and encouraged each other… At 2030 we closed the ports and started for Oran.

Brigadier General Frederick A. BLESSE, NATOUSA Theater Surgeon. Picture taken in 1943.

Friday, 16 July 1943 > At Sea + Algeria. I have been in the OR all night picking shrapnel out of people, patching up others, and re-dressing the burn cases. In this short run we’re only able to handle the worst and emergency cases and the Hospitals at Oran will continue the work. The doctors and half of my unit worked all through the night as we have to turn complete medical records on the cases as well as take care of them physically. As soon as we reach Oran, we have to unload our patients, take on water, run the laundry for the first time, and wash all the dirty linen before we leave. As we left Algiers, 2 British Hospital Ships had been ordered to Sicily as the Italians and the Germans were beginning to fight back and our casualties were increasing. It is 1100 and we are in Oran at pier 14. Colonel Howard J. Hutter and Colonel Joseph G. Cocke (Headquarters, Mediterranean Base Section –ed) meet us at the dock. However, we don’t get fully docked until 1530 hours as the wind keeps blowing the ship away from the pier. The boat was finally stable and the patients were debarked in just four hours. 808 patients, half of them litter cases. I called the girls at the 40th Station Hospital (Arzew, 18 January 1943 > 4 March 1943; Mostaganem, 4 March 1943 > 15 January 1944 –ed) and told them to come down to the ship if they can get away. Major General A. R. Wilson has gotten tough on his Officers; he felt they were getting too much food and put them on a C-Ration diet for two weeks. He found an ice box in a Lieutenant’s quarters, and the man was fined $ 50.00. After having dinner with Colonel H. J. Hutter in his villa near Mers-el-Kébir, I returned to the ship to find it completely cleaned and ready to take on more patients. I hope we can stay here for a couple of days as there are a great many minor repairs needed and I want to get enough water to run the laundry efficiently. As it hasn’t rained here for three months, they may not give us enough.

Saturday, 17 July 1943 > Algeria. Busy all morning with the routine port affairs and paperwork. I arranged with Headquarters to take the girls and the Enlisted Men out to the beach at Ain-et-Turk in trucks at 1300 hours and while they were gone, Colonel Theodore L. Finley, Deputy to Brigadier General T. B. Larkin, came down to the boat for a short inspection and invited my Nurses to the opening ball of the SOS in Oran at 1930 tonight. He promised to come for us with the necessary trucks. The boys worked on the laundry almost the entire day and discovered that some of the parts were broken. Fortunately we found some local men who will weld them for us and we hope to get the job started this afternoon. 1400 hours and the first 100 sheets have gone through the wash and they really look good. If we stay here a couple of days we can have all clean linen for a next trip. The dance was quite an affair of mixed civilians and military and was held in the Marriage Room of the City Hall with a colored orchestra playing. There I met Brigadier General Thomas B. Larkin (CG > USASOS, NATOUSA –ed) and when I told him I was the CO of the “Acadia”, he said: “Yes, I know, you’re sailing for Sicily in the morning.” I told him, maybe, but neither I nor the Captain knows anything about this. When we returned to the boat, word was waiting at the gangplank that we were to sail at 0630 the next morning, but no destination was given. That finished the laundry until we reach another port where we can get water.

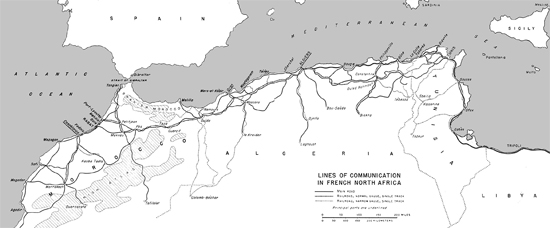

Overall map of North Africa and the Mediterranean region.

Sunday, 18 July 1943 > At Sea. Our boat left as scheduled and we follow the coastline to keep away from convoy lanes and as far from the Italian base at Sardinia as possible. Our orders are to proceed to Bizerte, Tunisia, and we should reach our destination about 1500 tomorrow afternoon. At 1600 we passed a large troop convoy going our way too. Just after that, two P-39 Airacobra fighters flew over us several times checking us and the lanes ahead for any submarines. It is now 1900 and we can see Algiers in the distance and the burning Army transport that was torpedoed near the harbor yesterday. It seems that we always come in or leave after something happens.

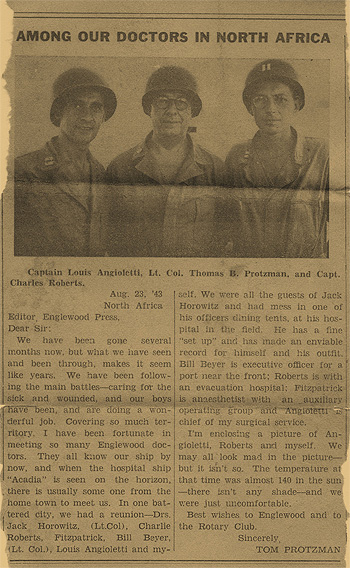

Monday, 19 July 1943 > At Sea + Tunisia. We are still at sea. We are about three hours from Bizerte. Early this morning we sighted a convoy that covered the entire horizon, quite an amazing and awe inspiring sight. Shortly after daylight, 4 groups of fifty bombers passed over our ship going in the direction of Italy. At 1530 we are anchored off the shore of Bizerte, Tunisia. Two British Hospital Ships, HMHS #24 and HMHS #33, are near us. We also see USAHS “Seminole” alongside a wharf in the harbor. The town seems like having been badly shot up and many sunken vessels can been seen in the harbor. Several Allied submarines have come near us and gone into Bizerte harbor. The sky is full of planes. It’s so incredibly hot that we are sitting around in our shorts only. Imagine, it must be terribly hot in the desert. I learn that the “Seminole” brought in 200 wounded from Sicily and left them here. Dr. Jack Harowitz of Englewood, came over to visit, he commands the 53d Station Hospital. We had a little reunion and if we remain here another night, I will be able to take my crowd along to his place for a little party. The 3d General Hospital and some other units such as the 56th Evacuation Hospital, the 78th Station Hospital and the 81st Station Hospital are not far away. I stopped at the AGO Office for orders and they didn’t know we had arrived. There are no orders as yet, but we think we will probably go back to Algiers and take a load of patients back to the States. Anyway, we saw what was left of Bizerte. Everything in the harbor is blacked out completely including the 4 Hospital Ships! The “Seminole” is lying alongside my ship now.

USAHS Seminole, US Army Hospital Ship (while in New York POE, 1943).

other US Army Hospitals in the Bizerte-Tunis area, Tunisia, during the period

38th Evacuation Hospital (750 beds, Tunis, 20 June 1943 > 24 August 1943)

56th Evacuation (750 beds, Bizerte, 20 June 1943 > 17 September 1943)

53d Station Hospital (250 beds, Bizerte, 27 June 1943 > 12 January 1944)

54th Station Hospital (250 beds, Tunis, 28 June 1943 > 30 August 1944)

78th Station Hospital (500 beds, Bizerte, 1 July 1943 > 15 March 1944)

114th Station Hospital (500 beds, Ferryville, 2 July 1943 > 10 May 1944)

58th Station Hospital (250 beds, Tunis, 5 July 1943 > 29 December 1943)

9th Evacuation Hospital (750 beds, Ferryville, 9 July 1943 > 6 September 1943)

81st Station Hospital (500 beds, Bizerte, 12 July 1943 > 4 April 1944)

3d General Hospital (1000 beds, Mateur, 13 July 1943 > 22 April 1944)

43d Station Hospital (250 beds, Bizerte, 19 July 1943 > 12 January 1944)

Tuesday, 20 July 1943 > Tunisia. Early this morning I went ashore with some of my Officers to try and get some information out of the British in charge, when I picked up a buzzer message ordering all ships into Lake Bizerte for safety as an attack of some sort was expected. It certainly pays to learn the international morse code. I called my men and we returned to the boat and were on our way into the Lake. The French pilot was already on board and I had to do the talking. The Lake, several miles back in the hills, can only be reached through a narrow channel filled with sunken ships. During the trip we hit something with our starboard side, the boat was so close to shore that everyone had a good look at the ruins of the city. The heat is appalling, 102° F in my cabin, and 130° F on deck. It’s like walking out into a furnace, the deck is so hot that we even had to shut off the ventilators as they were only blowing hot air into the ship. The Lake is of considerable size, with salt water, and there must be several thousand ships at anchor here, yet it seems empty. Small Arab villages dot the shores, they appear so white and spotless in the sun, yet, death and misery lurks in every house and tent. We had an incident several days ago; some men broke into the alcohol and narcotics locker and drank the alcohol. While ashore at Oran, Captain Hoffman, one of the Medical Officers who used to work for the State Police, found and developed the fingerprints and compared them with the ones on the GC identification cards. We found the two culprits who broke into the locker and the three guys who drank the alcohol. They got a pretty stiff sentence.

Wednesday, 21 July 1943 > Tunisia. Still at Lake Bizerte. Although it cooled a little during the night, we are in the middle of a blistering day. I called in one of the Navy boats and sent all the EM ashore with light equipment for an ‘official’ hike, and have advised the NCO in charge to take them only to some scenic and interesting places. This way my boys can see the place and we won’t be interfering with British regulations. The afternoon we will take the Officers and the Nurses on a similar trip to one of the beaches. Meanwhile divers came over from the Navy repair ship and found out that we have badly bent three blades of the starboard propeller. I don’t know whether that may interfere with our further plans as the nearest dry dock is either at Algiers or Oran. We can still run with a damaged propeller but it will cause some considerable vibration. The temperature dropped to 110° F today and there is now a small breeze blowing, but there isn’t any shade. Restful sleep aboard is impossible, you wake up in the morning with a heat hangover and a bad disposition. If we remain here any length of time, it is going to be difficult to keep up morale.

Thursday, 22 July 1943 > Tunisia. We started out at 0830 and went to Karouba, a small native village about three miles from our anchorage where our Navy has a small boat base and from where we get our water transportation. Lieutenant Buckley, USN, is in charge here, he is one of the boys we brought over last year. He also loaned us a light truck. We passed an airplane dump where hundreds of German and Italian aircraft were piled in heaps; they had all been either shot down or abandoned and what wasn’t demolished had been finished by the soldiers as they passed by and tore off war souvenirs. From Karouba, we went to Mateur and crossed the battlefields just vacated a few weeks before. The only things that had been removed were the dead, but the place was still littered with broken guns and equipment of a defeated army. It was too dangerous to wander over the fields as very few mines had been removed. The road was rough and bumpy and I lost one of my cameras. About three miles out of Mateur, one of the brakes overheated and froze, and we pulled in at the 188th Ordnance Depot to have it fixed. The detachment was housed in tents on a perfectly barren field with a temperature of 140° F. While they were repairing our vehicle, we had dinner with them on K-rations, with some synthetic lemonade with real ice in it. I called Ed Bick on the radio and he came over driving an ambulance. His place was about ten miles away with the 3d General Hospital (at Mateur) and we were certainly happy to see each other again. The Hospital was first held by the French, then it was taken over by the Germans, and after they were driven out, the Americans took over the place for their own use. The 3d General Hospital was now filling up rapidly as wounded were being flown directly there from Sicily, with about 200 hundred patients arriving by air evacuation every evening, around 2300 hours. Just outside Mateur, we passed an enormous airfield filled with twin-engined P-38 Lightning fighter-bombers ready to go into action, and just outside of Karouba was a similar field with lots of British Spitfires. A common sight is to see several hundred Allied planes in the air, going or coming. We visited famous Hill 609 where so many of our boys from the 34th Infantry Division were lost.

Friday, 23 July 1943 > Tunisia. We all remained on deck late last night as the heat was impossible to bear. Later in the day, HMHS “Oxfordshire” pulled in and dropped anchor near us. This makes a total of 5 Hospital Ships in Lake Bizerte and more cargo ships are still coming in too. The place is a forest of masts, I wonder what is happening, and why we’re all here, doing nothing. It was about 1400, and while I was trying to cool myself under the awning on the top deck in my shorts, the Officers of HMHS “Oxfordshire, accompanied by their Superintendent Nurses, Colonel H. J. Hutter (Head Medical Section, Headquarters, Mediterranean Base Section –ed) from MBS Oran, Colonel Henry S. Blesse (brother of Brigadier General Frederick A. Blesse, later Deputy Commander > Anzio Beachhead, CO > 56th Evacuation Hospital, and Surgeon Fifth United States Army –ed), and Captain Charlie Roberts (9th Evacuation Hospital Staff –ed) dropped in on me for a courtesy visit and to get some whiskey and soda. The temperature outside was 140° F in the sun and 130° F under the awning. The temperature in my cabin was only 96° F. Unfortunately no liquor can legally be served on a US vessel unless by prescription, so we all had to retire to my quarters and sweat it out there. I didn’t drink, as I need to keep my head clear and this socializing is a good way to obtain information. General F. A. Blesse was in Bizerte yesterday and when he saw 5 inactive Hospital Ships he got quite angry as many wounded are being brought from Sicily in landing craft. He hopes to get us out of here by tomorrow. By talking to some of our patients, we try plotting their positions on our map so we can tell where the Americans and the British are in Sicily and by this time the island is practically in our hands. Now that the enemy bombing is over, Bizerte has installed an air raid siren. It started to blow while we were in port and when we made a break for one the cellars we were told that it was only a test. The heat and the closed confinement on the boat without any work and little recreation are beginning to present problems that are difficult to handle. Nurses started mingling with Enlisted personnel, and better discipline will have to be enforced. Right this minute, I would give a great deal for a Hospital full of patients! The ARC girls are trying to arrange a party for the Nurses on the top deck this late afternoon and Officers from the surrounding ships and shore bases will be invited, so maybe this will help relieve some of the tension with the women, but it doesn’t solve the frustrations of the EM. I’m trying to obtain transportation to Ferryville for them this afternoon so they can browse around for a couple of hours. We need work, this ship is so clean that a self-respecting fly wouldn’t come aboard.

Saturday, 24 July 1943 > Tunisia. The place is still under terrific tension and I have a feeling something will happen soon. Besides the thousands of vessels in Lake Bizerte, there are 90 assault landing craft loaded with troops in the outer harbor now and think that in just one evening run we could be in Italy proper. I hope this is the time for us, and that we will go in with the assault troops. Lt. Colonel Gerding, S-4 (Supply & Evacuation Staff Section –ed) of the 8th Port, spent the afternoon on the boat with part of his staff and told me that the “Acadia” was going to Italy. It seems that several of the Navy ships have been ordered to stand by and be ready to sail by 28 July. The girls got their party and dance from 1830 to 2130 and had a real nice time. A couple of Nurses from the 168th Evacuation Hospital came over for a while, they had been following the frontlines ever since November and lost all their clothes; they were in their OD fatigues and had been wearing sneakers for the past nine months as regular Army shoes are too large for them. A couple of our girls gave them their leather shoes.

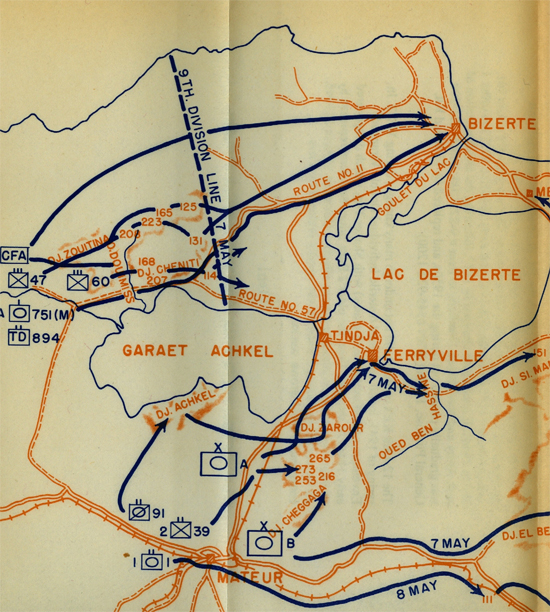

Part of 1943 military map showing Lake Bizerte, Tunisia (including major towns in the area, such as Bizerte, Ferryville, Mateur).

Sunday, 25 July 1943 > Tunisia. Still at Lake Bizerte and without work. At 0830 we left by boat for Karouba and I called on Lt. Colonel Gerding who took 5 of my Officers and 8 of my Nurses to visit the 53d Station Hospital on “Hospital row” outside of Bizerte. It was terribly dusty and I understand now why dust masks were issued. From the Hospital we drove to the top of the hills where the 56th Evacuation Hospital is located in some permanent ex-French Army barracks; Colonel H. S. Blesse is in command. While he was showing us around, there was an air raid alert and an Italian fighter passed high over the hills going towards Algeria. Several of our Nurses and some of my Officers took the evening meal on one of the LSTs (Landing Ship Tank –ed) near here and while they were enjoying it, the vessel received orders to move. They needed to load a Quartermaster unit that is going to Sicily next morning. This may or may not mean something… I had a late cup of tea with Captain Maxwell of the “Oxfordshire”. After returning on the ship, it still is 94° F in my cabin with absolutely no signs of any cooling, and it’s too dangerous to remain on deck on account of the numerous mosquitoes.

Monday, 26 July 1943 > Tunisia. Lake Bizerte. Another hot day has started with dust storms sweeping across the Lake; you just can’t stay on deck very long. We have heard all sorts of rumors about Italy, Benito Mussolini, but we can’t believe much of it. The sailors and some of my boys have collected a lot of German and Italian booty; mainly guns, but we can’t keep them on the boat, as it would be against our neutrality. Tomorrow they will have to go. 4 of our Nurses and 4 Officers attended a dance at HMHS “Oxfordshire” this evening. While on the ship, everyone was drinking hard liquor except me. They served me what looked and tasted like orangeade; it even had orange pulp in it with an occasional seed. Captain Maxwell, the skipper, told me it was made of citric acid, sugar, and carrots, and that they hadn’t seen an orange in England for the last four years. We took them some oranges and apples. If the opportunity presents itself, I’m going to take a quick unofficial trip to Tunis and visit the ruins of Carthage.

Tuesday, 27 July 1943 > Tunisia. I got away early this morning with the intention of visiting a few Hospitals, the city of Tunis, and the ruins of Carthage. The latter is just a jumble of crumbled rocks and stone where one can still purchase ancient Roman coins (reputed to be original). Tunis was more interesting and there was not the destruction as in Bizerte and in Mateur. I understand a sound Persian rug can be bought for a few pounds of tea, or a pack of cigarettes, but I had neither. During the whole trip we were in the midst of a sirocco (hot southern wind with dust and sand). Tunisia is no country to be in during the summer months; the ground is parched, the surface cracked wide open for lack of moisture, and the only shade to find is a few stubby olive trees, an occasional palm, and a few trees that look like sycamores. I returned early in the afternoon to a ship that seemed hotter than the desert. While resting, we watched a flight of Spitfires over the Lake, and suddenly one of them exploded in midair and crashed. No reaction, not even a murmur, we have seen so many deaths and destruction that the loss of one life and the destruction of dollars worth of Government property doesn’t stir us. Lake Bizerte is now filling with LCIs (Landing Craft Infantry –ed) and it looks like something is cooking… We’re all praying that the “Acadia” will go in with the next invasion.

Wednesday, 28 July 1943 > Tunisia + At Sea. Early this morning we received word that we were to prepare to leave Lake Bizerte at 1000. Captain “Jack” received the necessary instructions, and we then sent a cable to have a new propeller ready for when we return. Our sailing time has now been changed to 1530. Upon instructions from one of the local Army Colonels of the Port Authority (who doesn’t know anything about naval matters), we underwent a new investigation and another diver came up with a total different report indicating that the damage caused to the bent starboard propeller wasn’t that bad. One of the Navy Officers of the USS “Delta”, AR-9, another of our Navy’s repair ships (in service 1943-1947, served in the Mediterranean –ed), said that a good many destroyers at sea were operating with worse blades than ours, so to go ahead and do the best we could. The Captain is yelling at the French pilot; he is getting so irritable and touchy that no one wants to go near him. The nearer we approach action, the more he becomes mentally upset and stressed as the safety of the ship is his responsibility. The pilot had heard that Palermo, Sicily, was full of dysentery and malaria and the locals were starving. As we passed through the channel, the outer harbor was filled with assault landing craft of all descriptions filled with troops and equipment. Maybe we will see some action after all.

Thursday, 29 July 1943 > At Sea + Sicily. It is 0600 in the morning and we are off the coast of Sicily. It looks just as mountainous and foggy as the coast of North Africa. One of our small destroyers picked us up and we followed her through the minefields in the swept channel, as the course that had been plotted for us at Bizerte seemed incorrect or had been changed. Ahead of us are several minesweepers, working in groups of four with their little red flags trailing far behind them at the end of the magnetic cables used to trap and explode the mines. These boys really lead a tough life as they never know when they will get blown up and get no glory from battle. From a distance, the city seems much larger than any we have entered. To the right and extending out into the bay is a large hill very similar to The Rock of Gibraltar and on tops stands a beautiful hotel that I understand is occupied by General G.S. Patton, Jr. (CG > Seventh United States Army –ed), and I hope he remembers the two turkeys we sent him last Christmas. The whole situation looks ghastly, much the appearance of Carthage; Palermo is a dead city. The Port Officer ordered us to drop anchor 1400 yards from shore and to beat it in case the harbor was attacked. As soon as we dropped anchor, another destroyer pulled alongside with wounded that had been involved in shore attacks the previous evening. Another destroyer had suffered a near miss and was put out of action. The ship had been towed into Palermo for partial repairs and will be out of commission for at least six months as its whole side had caved in. I had one of my Officers with me and two of the girls (I find it much easier to get by any guards into a restricted or forbidden area if we take a couple of the best looking Nurses with us). Second Lieutenant Franklin D. Roosevelt, Jr. (US Navy Ensign 1941-1946, served in North Africa, Europe, and the Pacific –ed) was the XO on this boat and has been here for two years. He seems a likeable chap and his men speak highly of him; he looks very much like his old man (son of FDR, 32d President of the US –ed). Several of us went ashore on a PTB that brought some wounded Officers back, and as we left a whole fleet of small destroyers and PT boats sped out to sea on some sort of mission. We reported in at the Port Director’s Office, a Captain Doughty, USN, who directed us to Seventh US Army Headquarters in the Post Office building in the city. The Headquarters is located in a beautiful marble structure in Palermo’s center and is practically intact. Marble busts and portraits of the “Duce” and the King (Victor Emmanuel III, 1869-1947 –ed) are still present in prominent places. The harbor itself is blocked with sunken ships and from the shoreline to the city for about ten blocks there is nothing but complete destruction. It’s amazing how quickly we have been able to take over the entire city. MPs are everywhere, directing traffic and Italian Carabinieri in their gorgeous uniforms have been given armbands in English and patrol the streets. Italian soldiers are still coming in and surrender faster than we can take care of them. Colonel Daniel Franklin (Surgeon, Seventh United States Army –ed), told me he had been cabling for the past three days in an attempt to get the “Acadia” over here and clear the wounded out of the Field Hospitals so they would be able to care for those that would be wounded in the coming battles.

Patients are now being evacuated from the front, and we will begin loading sometime this afternoon from landing barges, as the Port Director doesn’t feel it is safe enough in the harbor for a ship of our type and size. I saw a couple of stray dogs looking for food; they were walking skeletons and made my heart ache. When the very few people and kids saw us on the streets with our GC brassards, they thought we were from the American Red Cross and kept crying “Please give us food.”They had been informed by their Government that the ARC would feed them. They are a poor starved lot and haven’t had much to eat for months. The Allies have taken over the Government and are issuing Allied currency which the locals want in preference to their cash. While we were going through the docks with some of my Nurses, a company of doughs marched and kept staring at the strange sight of American women so damn near the front. The girls are a great morale booster. Colonel D. Franklin just flashed us that there would be no patients until tomorrow.

US Army Hospital in Palermo, Sicily, during the period

91st Evacuation Hospital (400 beds, Palermo, 27 July 1943 > 31 October 1943)