Timeline USS “Hope” AH-7 – Colonel Thomas B. Protzman 215th Medical Hospital Ship Complement - Part II

Friday, 1 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We passed a large convoy last evening and the swells are making a few of the new Nurses sick. The rest of the day was uneventful.

Saturday, 2 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. A great many cargo planes passed overhead all day on our route to Leyte, but no convoys were seen. Early in the evening we passed the “Bountiful” on its way to Hollandia, New Guinea, and they blinked us indicating they were carrying their full capacity of wounded.

Sunday, 3 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. Just before church services this morning, about 1000, the lookout sighted the periscope of a submarine that immediately submerged, and we didn’t think of it anymore until 1600 hours this afternoon. It was presumed to be an enemy sub shadowing the “Hope”.

As it’s very hot I was sitting in my shorts listening to some rebroadcast of the Army and Navy Games, when the alarm went off with a bang! I stuck my head out of the porthole, just in time to see a Jap plane diving at our port side and loose an aerial torpedo. We are off the coast of Mindanao at the time. The torpedo hit the water and started for the ship, but the Captain swung the “Hope” over in a sharp turn, and it went harmlessly by. The Nurses were all on the top side but none lost their heads or even became exceptionally excited. We meanwhile sent out a general call on the radio that we were being attacked and gave our position. After the unsuccessful attack, the enemy plane did not close in for strafing. It looks like our trip to Leyte may become more exciting than the last one.

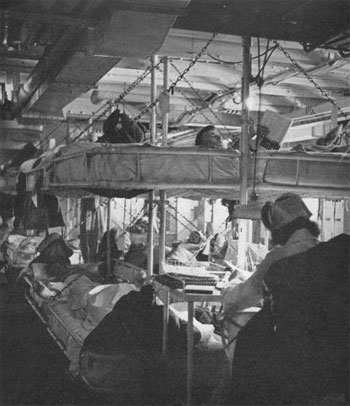

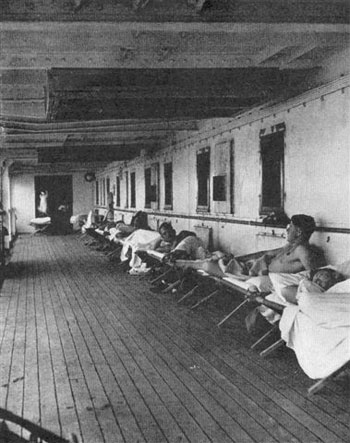

Typical view of a hospital ward on board a US Navy Hospital Ship. Picture taken in 1943.

Monday, 4 December 1944: Pacific Ocean, Leyte Island, Philippines. It’s almost sixty miles into the harbor from “Desolation Point” (navigation light set up by US Rangers on Dinagat Island, Surigao Strait, to guide incoming vessels –ed) and the first three miles are made in total darkness. It is surprising how much can be seen when you train your eyes for the job. The harbor entrance is being guarded by 4 heavy cruisers and 7 destroyers on continuous patrol duty. We must have been quite a sight to them all lit up like a Christmas tree. About 0800, we were at anchor. Rumor has it that due to the heavy mud and rains, the invasion of Luzon has been postponed for about ten days or more. There has been 23 inches of rainfall here in the last thirty days. The 120 Nurses were discharged here.

My Nurses and other Officers got off the ship early in the afternoon and while they were being transported to shore, a boat came alongside with 55 survivors of the USS “Cooper” (DD-695), which had been blown up by a Jap kamikaze bomber in Ormoc Bay 3 December, causing the loss of 191 crewmen. Another destroyer was sunk and 3 battleships put out of commission last night by 5 suicide planes. The battleships and the other “tin can” entered the harbor this morning and their wounded are being sent over to our ship. These men are in a terrible condition; besides their wounds and blast injuries they all are severely burned. Several of the wounded died shortly after admission and we sent the bodies ashore for a decent burial. All day long we continued to load wounded from this action and didn’t leave the ORs until after midnight. I’m going ashore with First Lieutenant C. W. Kersten, MAC, to try and contact HQ as we have a large supply of medical necessities for the Hospitals and no way of notifying the proper people. There was one light air raid but no damage was done.

Medical Support on Leyte Island (1944)

Tacloban area, 26 October 1944)

16th, 19th, 27th Portable Surgical Hospitals

36th Evacuation Hospital

58th Evacuation Hospital

135th Medical Battalion

135th Medical Group

262d Amphibious Medical Battalion

400th Medical Collecting Company

893d Medical Clearing Company

Dulag area, 26 October 1944

7th, 51st, 52d Portable Surgical Hospitals

69th Field Hospital

71st Medical Battalion

76th, 165th Station Hospitals

262d Amphibious Medical Battalion

394th Medical Clearing Company

644th, 645th Medical Collecting Companies

Tuesday, 5 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines. We had several air alerts last night but saw no planes. Lieutenant Kersten and I were put ashore at Red Beach and went to the CP of the Engineer Battalion to try and reach Headquarters on the phone. I did get through but they just couldn’t hear me, so we walked and thumbed our way through a sea of mud to the motor pool and finally reached Tacloban. It took us almost two hours to drive five miles in a heavy truck. Rough terrain, coral reefs, and rocks on shore make it almost impossible to erect docks, so all supplies have to be transferred to the beach from the ships in small landing craft, with the exception of one separate dock that will only accommodate three Liberty Ships at once. Defeat of the enemy is being seriously delayed because of the inability to get the necessary supplies to the front, the greatest hindrance being the mud. Lt. Colonel Paul O. Wells, Base “K” Surgeon (Tacloban), told me that the Filipinos were apparently well-treated by the Japanese and that their women were not molested. After reaching Headquarters, I found Major Arthur Weiss and Ike Wiles (Monmouth friends). Weiss was in the Invasion and Ike is with the Civil Affairs Section, Sixth United States Army. The hospitals are full and functioning as best they can in the mud. Two General Hospitals have arrived but it’s impossible to set them up in this weather, and Engineers and Seabees are continuously trying to keep the roads passable so they can bring in ammo to the men and evacuate the casualties. The only exception was the 133d General Hospital which arrived by LST on 25 November. Consequently, only 2,400 beds were in operation on the island (out of 8,500 present on Leyte –ed).

Our orders were to sail this afternoon, but I convinced Headquarters to let us remain here until all our hospital beds are full, no matter how many days this may take. Every man we can take out of here will help; they only have 30 ambulances here to transfer the wounded to the beaches. While ashore, there was another air raid. Lt. Colonel P. O. Wells was glad to hear we had supplies for him and he took us out in an LCVP to collect them. On our way to the beach we passed Tacloban airfield and saw its edges strewn with wrecked planes, aircraft we lost on D-Day. We apparently lost 85% of our fighters that same day.

Colonel T. S. Voorhees and Lt. Colonel P. O. Wells came to the “Hope”, and from there on we visited the Fleet Surgeon, Captain Albert T. Walker. With these three men I hope to obtain permission to remain at Leyte Island as long as possible to aid the overcrowded hospitals and to secure better transportation for the wounded. The Navy doesn’t want that responsibility; I don’t mean the men over here, but the brass that write the orders in Washington. Colonel T. S. Voorhees will try and straighten this out upon his return to the Zone of Interior at the end of the month.

The conference was very successful. As we had only 400 patients on board by the evening, I’m happy to learn that we will remain here until fully loaded. The wounded already aboard are badly messed up and many of them are severely burned too. It will take us the greater part of the night to get them out of danger.

US Navy Hospital Ship. A bad burn case from one of the kamikaze attacks has had his wounds dressed and is lying in comparative comfort.

Wednesday, 6 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines, Pacific Ocean. I was in bed at 0045. One hour later I was awakened by the night watch saying there was a radiogram from an LCI that was bringing in casualties from a torpedoed attack transport, all wounded or burn cases. I immediately dressed and had the surgical and shock teams ready and then went on deck just in time to see three red flares shoot in the air. In only a few minutes the CWS guys had a smoke screen to cover the airfield which slowly swept over San Pedro Bay. It’s going to be difficult now for the incoming LCI to find us in this artificial fog. We didn’t have long to wait till the shore batteries began to fire and the shells started to burst overhead spraying bits of shrapnel on the ship and on us. The airfield was heavily bombed and several nearby hits rocked the “Hope” considerably giving our patients the jitters. We had three heavy raids during the nights with many bombs dropping uncomfortably close. The reason they left us alone last night was because the Japs were attacking a convoy in the outer harbor. About 0300 the LCI came alongside, almost like a ghost through the smoke, and we first took in the more severely wounded. The others will have to wait until daybreak. We didn’t dare turn on our lights using whatever little moonlight filtered through the fog, as there were still Jap planes overhead. The LCI’s deck was lined with charred masses and crippled bodies, many of them burned badly. We operated throughout the rest of the night during the raids. After dawn, another ship came alongside with more wounded and dead from another transport that had been hit by a kamikaze. The casualties belonged to the 149th Infantry Regiment, 38th Infantry Division, on their way to the next assault. We were now working at full speed, trying to care for the wounded who were coming aboard faster than we could treat them. We had a total of 655 patients aboard now.

After having been attacked in the open sea in broad daylight off Mindanao, the Skipper had requested a change of course so we can return to Manus Island between Palau and Yap Islands, that way we will be closer to the regular sea and air routes and get some more protection on the way down. We don’t want to take any extra chances with this ship and its human cargo. In case of severe bombing, strafing, or torpedoing, we would never be able to get all the wounded off the ship in time!

At 1500 hours we received orders to sail at 1600 and will use the new route. At 1800 we passed the warships guarding Surigao Straits. I was listening to our short-wave radio when suddenly another voice broke in indicating there was a number of unidentified “bogies” coming up the Straits and requesting us to be on the watch. I went on deck and witnessed a dramatic battle between our carrier-borne aircraft, our antiaircraft guns, and the enemy attackers. Several planes were shot down, but being too far, we couldn’t determine whether any damage was done to our ships. The air was filled with exploding shells. It doesn’t seem possible for a plane to get through such a wall of fire, but they do. Just as we thought the shell fire was slackening and we started below deck to do some more dressing, the lookout sited an incoming plane off our starboard bow. We didn’t pay attention until a first bomb landed harmlessly off the starboard beam rocking our ship considerably. The Jap dropped another one and missed again and then took off. Being fully illuminated in accordance with international procedures there was no mistake, the enemy had deliberately tried to sink us. With our load of wounded it would have been a disaster! It took quite some time to quiet some of the patients and sedation was the only remedy. Nothing else happened and we were able to finish operating the worst cases by midnight. The last 5 wounded we took aboard had served on the USS “Cooper” which had sunk in only forty five seconds. They had been in the water for over eighteen hours, swam ashore to Jap territory, were rescued by Filipino guerrillas and carried on water buffaloes to American lines, and flown to Tacloban airfield, Leyte, by friendly aircraft.

Thursday, 7 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. This day has been uneventful with the exception of a staggering amount of orthopedic surgery and the care of our burn cases.

Friday, 8 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. Same as yesterday, except that it rained all day.

Saturday, 9 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We removed some shrapnel out of some heads today and operated on some eye cases. The worst of our cases are done, but we still spend a great deal of time on our burn cases. It’s so difficult to locate a vein in order to administer IV fluids and plasma. If they don’t get plasma, they will die.

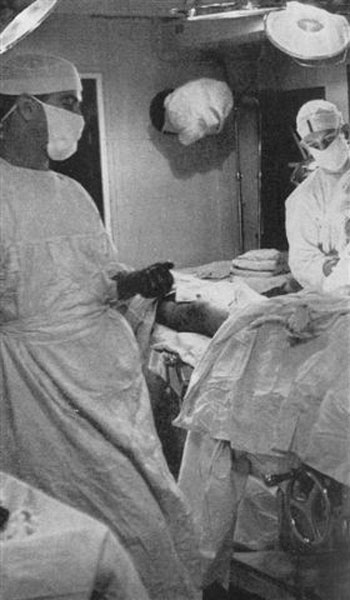

Partial view of a typical operating room on board of a US Navy Hospital Ship. The O.R. is fully equipped and is kept set up at all times, for any emergencies. Picture taken in January 1943.

Sunday, 10 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We have been making over sixteen knots for the last day or so and should arrive at Manus Island early next morning. They won’t be too pleased to see us as most of our cases are much too sick to fly and their bed capacity is only 1,500. In the afternoon we buried some of our patients at sea. It apparently didn’t upset the other wounded at all, they have been with death so long.

Monday, 11 December 1944: Manus Island, Admiralty Islands Group. We arrived in the mouth of the harbor at 0800 sharp just to see 3 “battle wagons” going past to practice maneuvers and anti-kamikaze dive fighters and bombers methods. There are several hundred ships here, including many “flattops” and “tin cans”. We were directed to a dock and started unloading from both sides. Our ambulatory patients were sent by barges directly to the airfield on Los Negros for air evacuation, while the litter cases were taken to the Navy Base Hospital. I accompanied the Base Surgeon to Los Negros Island and took the occasion to visit the 250-bed 59th Station Hospital there. The installation is set up in thatched native huts in a copra plantation. The scenery is peaceful and beautiful. The patients are all evacuated from here by air to Guadalcanal and can be moved at a rate of 200 a day. My Nurses and Officers have all been invited to a dance which is taking place at the Navy Base Hospital tonight. This is a real occasion, and they deserve it. The supplies we had wired for two months ago have arrived by air and we are really getting everything we need for our Hospital.

Shore view picture illustrating the explosion of the USS “Mount Hood” (AE-11), at Seeadler Harbor, 10 November 1944.

I’m thinking of an incident that occurred shortly after our last visit. The USS “Mount Hood” (AE-11), an ammunition supply ship, blew up in the harbor. She was carrying 3,800 tons of ammo and explosives and blew up on 10 November 1944 killing 295 men on board, another 49 in other ships, and wounding 371 sailors and soldiers in the harbor, as well as damaging a lot of other ships nearby. I remember the tragedy, as only a single crewman escaped; he was down three decks below when the explosion took place and was blown through the decks into the sea with scarcely a scratch!

Tuesday, 12 December 1944: Manus Island, Admiralty Islands Group. We received our orders and are to return immediately to Leyte in the Philippines. We will load the necessary supplies and take along a group of Nurses for the 38th Evacuation Hospital. They have been here on DS with the 59th Station awaiting orders. A number of men were on shore leave today to enjoy some rest. The weather is very calm, rainy, and unbearably hot and humid. We will be glad to return to the Philippines where it’s much cooler, but also much more dangerous.

Wednesday, 13 December 1944: Manus Island, Admiralty Islands Group. I almost forgot to mention the most important part of this trip. We picked up about twenty bags of recent mail. Also between one hundred and one hundred and twenty bags of mail have been flown to Hollandia, New Guinea, and we will retrieve them if we should happen to return to that place. Those letters and packages have injected new life into us all.

Medical Support on Manus Island (1944)

1st Cavalry Medical Squadron

27th, 30th Portable Surgical Hospitals

28th Malaria Survey Detachment

52d Malaria Control Detachment

58th Evacuation Hospital

603d Medical Clearing Company

Thursday, 14 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. The sea has quieted and the new Nurses we took on board aren’t so seasick. The boys have been cleaning the hospital wards and operating rooms and implemented the changes we find necessary from time to time. The rest of the day has been uneventful.

Friday, 15 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. Nothing to report.

Typical view of a (crowded) hospital ward on board a US Navy Hospital Ship. Picture taken course of 1944.

Saturday, 16 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We were off the Palau Group today and there was a lot of air traffic overhead, all friendlies. The girls have been busy preparing Christmas trimmings and decorations for the wards, as the ARC didn’t give us the right things. All personnel should be resting as we had a grueling trip and may run into a worse situation with all the extra action taking place during the fighting for Mindoro. Our radio says the American advance is unopposed, but that seems only a lot of bunk to us.

Sunday, 17 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We are in the area where we almost got clipped some weeks ago and believe you me the watch is very much on the alert. Our Catholic Chaplain, Lieutenant B. D. Mahedy, USNR, made a note in his sermon this morning saying it was God who saved us from the bombs and the torpedoes, and our Baptist Chaplain, First Lieutenant, M. E. Taylor, MC, is just as sure that it was his prayers to the Lord that saved us. To be honest I have my horseshoe and a great many of the colored crew boys carry a rabbit’s foot. We all feel that our charm did the work! I wonder who’s right?

At 0930 we sighted a Jap sampan a few miles of our port side and it kept with us for some time. We finally passed out of sight of the small boat but later saw a Navy bomber over that same area so she may have picked up the sampan or sunk it. We will hit “Desolation Point” soon and reach Leyte harbor about 0430 in the morning.

Monday, 18 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines. The time is 0430 in the morning and the Captain thinks he can see the “Desolation Point” navigation light, I can’t see a damn thing but it must be so or we wouldn’t be steaming full speed ahead. So far nothing has happened and there’s no battle fleet around. It’s very hazy though and our ships may be nearer the shoreline than expected.

As we pulled into the bay the “Hope” was immediately surrounded by landing craft from the Mindoro landings (which took place 15-16 December 1944 –ed) and by noon we were nearly completely loaded with fresh battle casualties from the so-called ‘unopposed’ landings on Mindoro. The boys we just took in tell us that it was the worst Jap air attack they had ever witnessed and that the suicide bombings were terrible. Captain Mary Parker, ANC (Chief Nurse, Base “K”, who is with us), said that the last bunch of Nurses that we landed had been cut off completely from the main forces by a Jap attack, and it was some time before they were rescued. It is 1800 now and we’re still taking on casualties. Our beds have since long been filled and we are now putting the wounded on the mess hall tables and extra folding cots throughout the ship. This is by far the worst situation I have encountered. Fortunately, the USS “Mercy” has been called in early in the morning and will be able to pick up the remainder of the wounded.

Tuesday, 19 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines. We worked all night and a little before daybreak I went on deck to get some fresh air, and just in time to hear the air alert go off. We were at anchor amidst a group of destroyers and could clearly hear their call to “General Quarters”, “Man Your Battle Stations” and the command to the gunners “Man Your Guns”. This is always a very tense moment as everyone is on the alert listening to the first sound of a plane or the scream of a bomb. The silence is very ominous. The wounded in our wards were all keyed up and some were ready to crawl under the bunks and tables.

Our fighter force drove off the “bogies” before they could drop a bomb. We departed Leyte Island with 708 casualties.

Wednesday, 20 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We left the harbor about 1100 yesterday morning and are now making a wide detour around Mindanao to avert any possible enemy attack. I operated on a boy who had his arm shot off at the shoulder by a 20mm explosive shell. Another gunner patient had all his fingers cut off as he was aiming his gun at enemy planes.

Thursday, 21 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We have about 200 serious burn cases aboard. Fortunately, the amount of plasma and dressings will far exceed that of the last trip. We estimate that we will use about 300 pounds of vaseline on the burn cases alone.

Friday, 22 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. We have buried 2 of our patients at sea today. It was a very beautiful and touching ceremony. I haven’t had much time to write as we all have been averaging over fifteen hours a day in the operating rooms and the wards.

Saturday, 23 December 1944: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. We arrived early in the morning but overshot the port by almost ten miles on account of the heavy rain and fog. We had to remain at anchor all day as there was no dock or pier ready to take us. One of our boats went in for the mail and returned about noon with a great load of packages and one bag of first class mail. The day before we were due, some fool shipped our other mail back to Manus.

Medical Support on New Guinea (1944)

5th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 13th, 16th, 17th, 22d, 24th Portable Surgical Hospitals

5th, 17th Malaria Survey Detachments

23d Field Hospital

107th Medical Battalion

116th Medical Battalion

262d Amphibious Medical Battalion

532d Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment

670th Medical Clearing Company

Sunday, 24 December 1944: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. We entered the harbor and proceeded to pier 2 at 0800 hours. I borrowed a jeep and paid a visit to Brigadier General G. B. Denit and Colonel Wascowicz. They will come down for dinner. I also talked to Walter Specht again. The USS “Hope” left Hollandia about 1900 hours with only one passenger; a Navy doctor heading for the front (read the Philippines).

Delicate operation on board a US Navy Hospital Ship.The surgeon uses a giant magnet in order to remove pieces of metal (shrapnel) from the patient’s eye.

Monday, 25 December 1944: Christmas, Pacific Ocean. At 0200 our ship picked up distress signals and the Skipper immediately put one of the radiomen on our direction finder, and by calculation we figure the signal originated about 200 miles ahead of us, which means we could reach their vicinity about 2300 tonight. The chance of missing any life rafts or small boats is great. Nearly everyone on the ship is dog tired after treating over 700 wounded and delivering them at Hollandia, New Guinea, yesterday. In spite of this, we’re all on deck at some time or other looking at the horizon and praying for the man or men who called for help. These small rafts have a sending device but cannot receive messages, so all we can do is listen.

Early in the afternoon we could here the lost men calling some aircraft that were visible to them, but apparently they just couldn’t make contact, what a hell of a way to spend Christmas! We followed their mayday calls until 1830 when they signed off with Merry Christmas. That took a lot of guts to send those few words, with the danger of having Japanese aircraft or ships picking up the call and come and destroy them. No more calls came through but around 2300 we sighted some wreckage and after a careful search decided that they were either lost, had sunk, or had been picked up by someone else. However, our Captain kept Lieutenant J. D. Rively, USNR, Radio Communications Officer on alert and about 0130 the next morning, the listener received a strong SOS signal and the crewmen on watch called down saying they had seen flares being sent up directly ahead of our ship, only a few miles away. In only minutes, many of us were on deck, and indeed dimly in the distance we could see a flashlight blinking morse code. We immediately sent down a reply and within less than one half hour we picked out the survivors with our searchlight, discovering two yellow-orange life rafts with 2 men in each one. I watched their faces through my binoculars and their expression was indescribable. All they could see was a lighted white ship which in itself was a strange sight in these times, just imagine we might be the enemy, which would make their plight worse. We took them on board. They were the crew of a C-46 aircraft en route from Finschhafen to Biak Island who got lost on their way. The pilot told me that they must have been following a false beam, as twice his radio compass registered land and when he came through the clouds he could only find the ocean. The last time he almost ran out of kerosene and was forced to ditch the plane. The reason they stopped sending a mayday signal after 1830 is that they had become so exhausted they all had fallen asleep. Just by chance one of them awakened when were only a few miles away and alerted his comrades. If the “Hope” had been blacked out, the ship would have passed them in the dark. They had been floating around in their rubber rafts for 30 hours.

Tuesday, 26 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. This morning our short-wave radio picked up the information that an enemy fleet was approaching Mindoro, so we can expect anything when we enter Leyte Gulf. First Sergeant Charles A. Dewey has checked our bed space and by careful re-arrangement in the forward mess and use of the main deck we can load almost 200 extra patients. One of the aviators we rescued last night is in a stage of complete hysteria and another seems stark mad. I don’t think the last one will ever fly again.

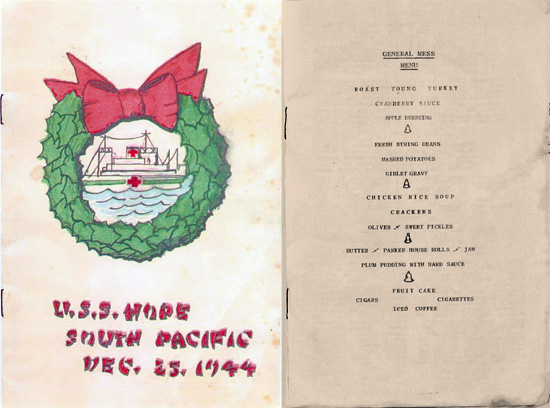

Cover of Christmas Dinner Menu held aboard the USS “Hope” on 25 December 1944, while sailing in the South Pacific. Courtesy Patricia Parker.

Wednesday, 27 December 1944: Pacific Ocean. No more news over the radio about Mindoro.

Thursday, 28 December 1944: Pacific Ocean, Leyte Island, Philippines. There’s no fleet at the harbor entrance to greet us, so it looks like all danger of an enemy sea attack must be gone. We didn’t get in until midday and saw the AHS “Maetsuycker” (Dutch Hospital Ship –ed) and the USAHS “Marigold” (US Army Hospital Ship –ed) in the harbor near Red Beach. We have been anchored all by ourselves in an isolated part of the bay, and it looks as though we might remain here for some time. There was a Jap airborne attack with some paratroops landing all around the 44th General Hospital. The medics and the orderlies grabbed some guns belonging to the patients and drove the attacking force away. By the time infantrymen arrived, the medical staff had everything under control. When night began to fall, destroyers put a heavy smoke screen over the fleet and left us sitting alone in the moonlight. If we get an air raid tonight, the only ship visible, will be the “Hope”.

Friday, 29 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines. There was no air raid last night and we’re still there at anchor. We were told to move nearer to the beach, just a little off Red Beach and not far away from the new airfield. We visited the “Marigold” and find she has carried 500 patients since she was commissioned 10 June 1944 and they’re not organized as we are to go near the frontlines and do emergency evacuation work.

Rumor has it that the US Navy intends to start a heavy bombardment on 3 January 1945 of the shores of Luzon Island, and that landings will start around 5 January (in fact they took place 9 January 1945 –ed). 2,000 pints of fresh blood are being drawn today to accompany the amphibious force. If we leave here soon, we can get back about 10 January, so we shouldn’t miss much of the action.

Litter evacuation on Leyte Island, Philippines. The wet season bringing lots of rain and mud made the terrain almost impassible for vehicles. Moving inland not only increased the distance between support units and advancing troops but slowed down evacuation as well affecting timely medical care of the many casualties.

Saturday, 30 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines. I went ashore this morning accompanied by Captain M. E. Kaiser, my Chief of Surgical Service, and First Lieutenant T. A. Griset, my Sanitary and Laboratory Officer. The trip to Tacloban, consumed only thirty minutes now. Four new dry docks and a considerable lot of work by our Engineers and Naval Construction Battalions have made the roads fairly passable. Of course, there’s always mud. We visited the native hospital in town and although it was packed with civilian and guerrilla patients, the place was clean and everything was conducted in an orderly manner. Although the enemy didn’t treat the Filipinos too badly, they nevertheless confiscated all their drugs, their linen, and their food. With our plentiful supply, they will be able to produce miracles.

We fought our way through the mud to the 126th General Hospital that is under construction. Colonel Ike Wiles is the Executive Officer (one of my friends from Monmouth). The place lies in a swamp in the thick jungle and the first loads of equipment had to be brought in by carabao and wagons (water buffalo –ed). Now they have some bulldozers and cement mixers and should be ready to receive the wounded from the Luzon operation. At daylight we watched 300 Army and Navy planes take off for Luzon. We returned to the “Hope” in the evening to find that only a few wounded had been loaded and that we’re not supposed to leave until 1 January.

Sunday, 31 December 1944: Leyte Island, Philippines. We loaded 200 patients today and will sail tomorrow no matter how many we get as they will need us back here for the forthcoming invasion. Major Arthur Weiss came aboard and joined me for dinner.

Monday, 1 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. At dusk the first air alert was sounded and we were almost under continuous alerts all night. Luckily only a few bombs were dropped our way and none of them came near us. Just before midnight a fierce battle took place along the shore and there was uninterrupted MG fire for quite a while. The tracers were rather low so we know it wasn’t an air raid but in all probability an enemy attack to destroy the airfield. By 0200 in early morning, the firing slackened and gradually ceased, but none of us went to bed as we feared the possibility of some of the Japs boarding our ship.

We found out later that the boys on the shore were just celebrating the New Year! I can tell you that Headquarters called for an investigation. Only a few people were injured. Out here, it looks like life, death, danger, and injury are part of the game, although the play is rough.

At 1500 the USS “Hope” sailed for Hollandia with only 313 patients on board and only a few of them in poor condition. By the way, it means we won’t get any mail this trip.

View of San Salvador Cathedral, Palo, Leyte Island, where the 36th Evacuation Hospital set up. The unit had previously served in New Guinea.

Tuesday, 2 January 1945: Pacific Ocean. We picked up another SOS signal this morning, but found after following it for a while that it was several hundred miles to our rear so gave it up.

Wednesday, 3 January 1945: Pacific Ocean. We are cruising on a much wider route this time to avoid the convoys that are coming up for the Luzon Invasion. At present we are way north of the Palau Group and won’t reach Hollandia until next Friday. We passed a large convoy last night. We have in one of our wards a boy whose both hands were blown off, with one eye gone, and both legs fractured, and we may have to amputate one as gas gangrene has set in the wound. He is smoking a cigarette, attached to his bandaged stump by some wire and a paper clip. We fortunately don’t have many cases like him, I mean so severely mutilated, but it makes me wonder what we as a nation will do for him. I hope, a much better job than after the First World War…

Thursday, 4 January 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful day.

Friday, 5 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. As we entered the bay, the most noticeable was the small number of ships at anchor, and the total lack of any ‘heavies’. What a golden opportunity for the enemy; a single battleship or a heavy cruiser would be worth sacrificing to wreck this harbor. The Japanese must have a shortage of warships or else are too busy elsewhere. There are at present 3 Hospital Ships ahead of us: AHS “Maetsuycker”, AHS “Tasman” (same status as AHS “Maetsuycker” –ed), and the USAHS “Marigold”. It looks as though we might remain here for a while.

New Guinea Bases (1944)

Base “A” – Milne Bay

Base “B” – Oro Bay (Buna)

Base “C” – Goodenough Island

Base “D” – Port Moresby

Base “E” – Hon Gulf (Lae)

Base “F” – Finschhafen (+ 26th Hospital Center)

Base “G” – Hollandia (+ 27th Hospital Center)

Base “H” – Biak Island (+ 28th Hospital Center)

Saturday, 6 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. We couldn’t unload directly, so I took Chaplain M. E. Taylor, First Lieutenant T. A. Griset, and Technician 4th Grade O. B. Aramini into the hills on a sightseeing trip and to visit the 19th Medical Laboratory. We got halfway when the jeep stopped – dead. We had to wait in the middle of a jungle road till a truck came along and helped us to a field repair shop. As they couldn’t fix the problem, I called a friend and he sent us some spare parts for the vehicle. While we were waiting for the spares we took off in the jungle and visited one of the native villages situated along a small stream. The locals certainly don’t look very fierce and were even very friendly. We exchanged gifts and talked with sign language and parted friends.

The hospitals are being gradually emptied for the next big push. The patients have been sent home on the transports and cargo ships that are bringing in the reinforcements and supplies for the coming campaign. One of my Nurses has located her husband on a transport and he’s coming over in a small boat to see her. What a coincidence, they haven’t seen each other for over a year.

I paid a short visit to Brigadier General G. B. Denit and he feels that this place will be closed by the middle of March 1945 and that everyone will then work out of the Philippines. This suits us all fine as we really hate the climate here. Our missing mail has finally caught up with us and it’s an enormous good feeling to know what is happening at home.

Sunday, 7 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. More mail came in today.

Monday, 8 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. We finally unloaded our human cargo today but were unable to leave the docks before 1400 hours. The “Mercy” came in from Lae (located across Huon Gulf, New Guinea –ed) with 600 medical troops destined for Leyte Island and left the same day. More mail arrived today. We took on 200 fresh units of whole blood. We don’t care how long we remain here just so the mail keeps coming as it does. It’s fantastic to receive mail only ten days old.

Tuesday, 9 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. The fight is on at Luzon Island, but it can’t be very bad or we wouldn’t still be here! I took another trip into the hills and the dust was so thick on the roads that we had to wear masks. Yet, you could step off the road into thick mud. This is the only place I know where you can stand in the mud and get dust in your eyes at the same time.

Wednesday, 10 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. Temperature reaches 86° but the humidity is lower and it is the first cool day we have had in this area since our arrival last Friday.

Thursday, 11 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. The S/S “Lurline” (ex-liner, troop transport –ed) which ferries American troops from the States to the Pacific Theater departed Hollandia with 900 wounded bound for the Zone of Interior. They will stop in Brisbane, Australia, and clean out some hospitals there too before proceeding home.

Friday, 12 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. Before breakfast this morning, we were precipitated onto deck by two heavy explosions. A Jap sub had shot two torpedoes into the harbor area from a distance at sea and one exploded on a reef about one half mile from the “Hope”, while the other exploded on the other side of the harbor. The air had suddenly filled with aircraft and some destroyers were on their way out to search and chase the attacker. The port authorities have ordered a complete blackout from now on. The “Bountiful” has just come in from Leyte with a little over 400 cases from the hospitals on the island. Resistance is light. The Navy has ordered all troop transports in the outer harbor to come inside for better protection. We have been warned to watch for any mines.

Illustration of the USS “Bountiful” (AH-9), US Navy Hospital Ship at sea in 1944. During September 1944 she serviced the Fleet at anchor off Manus Island, Admiralty Islands Group. By 1 January 1945, the “Bountiful” had treated ober 4,500 patients.

Saturday, 13 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. The Seventh Fleet Commander has ordered a board of investigation to be convened to examine the torpedo attack. This will probably take some time and delay our departure.

Sunday, 14 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. A freighter just missed hitting our stern this morning. We’d better move out of this place while we’re still afloat! Naval authorities have just issued us a 4-hour delay for the investigation, so we will probably not get out of here before Wednesday. There doesn’t seem to be much doing up the line, so we might as well remain in Hollandia and read our mail. It’s been like heaven, relaxing, and getting mail every day.

Monday, 15 January 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. Just as we were about to settle down for a long wait a message comes up ordering us to get up steam and sail at once for the Philippines. The investigation board visited our ship and have been taking affidavits all over the ship from every possible witness of the attack. In the meantime, Lieutenant A. Dunkley, USNR, the Engineering Officer is warming up the engines. This will certainly take several hours as we have been lying idle for so long.

Just before leaving at 1800 hours we exchanged our old blood reserves for fresh, and took on Lt. Colonel Paul Taylor, MC, from the Surgeon’s Office to Leyte (he was to become USAFPAC Medical Regulating Officer in April 1945 –ed).

Tuesday, 16 January 1945: Pacific Ocean. In the morning we passed a group of small whales. It proved very fascinating to watch the water spout. I tried convincing our Captain to go near enough for pictures but he refused.

Wednesday, 17 January 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful day with the exception that late at night we observed some green flares astern but couldn’t find out what they were. We have no such signals, but the Japs do.

Thursday, 18 January 1945: Pacific Ocean. Nothing really eventful happened today. Lt. Colonel P. Taylor explained how they flew over 700 PN cases to the United States from Hollandia. They are flown to Biak first, given a strong dose of castor oil, and then sedated before being put aboard the aircraft where they are kept on a litter with restricted movements of hands and feet. They are air evacuated to the States in forty eight hours.

Friday, 19 January 1945: San Pedro Bay, Leyte Island, Philippines. It was raining so heavily that we couldn’t see the headlands and we just had to circle around for several hours, passing the “Bountiful” three times in the process. As we entered San Pedro Bay, we were ordered down the coast (south) to Dulag where the worst fight, involving the 24th Infantry Division, took place on D-Day.

We learn that the landings on Luzon were made without too much enemy resistance with the exception of the kamikaze suicide planes that caused a number of Navy casualties and damaged some ships. We may be here for some time as there aren’t any wounded to take back. Later in the evening there were two alerts, but no bombs were dropped.

Shelltorn Church in Dulag, Leyte Island, used as a medical clearance and evacuation facility, with patients installed inside the building.

Saturday, 20 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. Less than 800 casualties here so far and they have mostly been evacuated to the USS “Refuge” (AH-11) which was at anchor when we came in. I left the “Hope” and went up the coast, northwards to Tacloban in a small landing craft which took nearly three hours. We hadn’t heard any bombs last night since they had been dropped on Tacloban killing 17 people and wounding 120. The town is still a mud hole and they had to close down the 49th General Hospital because of its bad location (swampy grounds).

Sunday, 21 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. We had one raid today and a single enemy plane which dropped a bomb near an LST, but no damage was done.

Monday, 22 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. I visited Dulag today in the company of some men of the 104th Engineer Combat Battalion (activated 20 February 1942, served in the Aleutians, Hawaii, Eniwetok, and the Philippines –ed). I met a lot of the boys I have known for years since I inducted them into the Army at the Teaneck Armory, and had landed here and built roads and bridges so the supplies could get through.

Tuesday, 23 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. The men on shore have offered the use of DUKWs, an amphibious vehicle, and early this morning we took off from the ship with 10 of our Nurses, 10 sailors, and 10 of my EM. We saw native women make clothing and dresses on old Singer sewing machines. I tried Spanish. But most of the locals speak a dialect of their own (Tagalog –ed), so I resorted to sign language and a few English words. A great many of them spoke some English but the Japanese occupation forces prohibited its use.

Wednesday, 24 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. One of our Nurses, Second Lieutenant Nellie G. Marsch, ANC, has discovered that her fiancé is somewhere on the beach near Dulag, so with 15 Nurses, 5 of my Officers, and a few Navy Officers we took off in a DUKW for the search. They’re wonderful vehicles as they can go anywhere on land, sea, and swamps without problems. After having covered almost a hundred miles, we discovered his camp, only to find out that the man had gone to a ship in search of his girl. Lieutenant Marsch and Sergeant Burk (USAAF) had been engaged for several years, but never could arrange for some time off. They missed each other when stationed in California; the ship the Sergeant was on sailed from Manus Island just a few days before our arrival. Long after dark we returned to the 104th Engineers Headquarters and just as we were about to leave, the ‘missing’ NCO appeared and I let them have about an hour together on the way back the “Hope”.

There are quite a few enemy in the hills and a few days ago they ambushed a supply train and killed all the guards. These bands are being hunted down and exterminated by the Filipino guerrillas.

Thursday, 25 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. I spent the day ashore with Miss N. G. Marsch and 5 other Nurses trying to find the proper way and authority to issue them a marriage license. I sent Sgt. Burk to Major Ralph Specht to ask and see what he can do to help. While we were on the island, two locals were found taking ammo and supplies to the Japs in the hills, and they were executed right on the spot by their own people. The whole beach area still reeks from the stench of poorly-buried bodies.

Provided there was some semblance of a road the use of ambulance jeeps (equipped with brackets to hold litters) was often the only method for evacuating casualties to the rear. If vehicles could not be used, it was up to the litter bearers to negotiate the often difficult terrain…

Friday, 26 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. Yesterday we moved down the beach near Tacloban, where we hope to find a local official for the wedding. We finally got in touch with the Mayor of Tacloban and he made out a marriage permit. It was quite a lengthy document and as there were no available printed certificates and no paper on which to type a new one, the back of revenue blank forms were used instead. We arranged for a party, when a troop convoy arrived into the harbor, and the wedding ceremony and party were to be postponed for another day. I sincerely hope nothing happens to stop it now.

A Japanese bomber was shot down over us last night.

Saturday, 27 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. The wedding party left our ship in the afternoon aboard a PT boat for Tacloban and when we were about half way we were all caught in a terrible tropical rain drenching most of the party to the skin. From the dock we continued wading through mud to the Court House and had to wait as the Mayor’s siesta wasn’t quite over. The Mayor was proud of having the honor of uniting the first ‘white’ couple on the island. He spoke excellent English, and since the real official was in jail for collaborating with the enemy, he was the acting Mayor. A lot more papers had to be made out on the backs of old documents, and then we discovered that the couple couldn’t be married in the Catholic Cathedral, because they were Protestant! I finally found a temporary Army Chapel near the Headquarters and a few weapon carriers hauled the party several miles through the mud and rain for the ceremony. Lieutenant Marsch and Sergeant Burk were finally married by our own Chaplain, First Lieutenant M. E. Taylor. The girls on the ship had prepared paper confetti and the boys had bought rice. After the ceremony, the Filipinos picked up the rice and I guess they thought we were nuts for wasting the food.

After returning the same way through mud and rain, the Nurses had prepared a reception for the couple in one of the ship’s mess halls. Captain Leona A. Soppe, my Chief Nurse, gave the couple her cabin for the night, as Sgt. Burk had to leave in the morning. What a strange world, these people may never see each other again, and barely had a few short hours of happiness. The wedding cost was 2 pesos.

Sunday, 28 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. We had an air raid last night and saw some heavy explosions with one large blaze which didn’t last very long. We ignore what was hit.

Monday, 29 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. It rained all day and we only picked up a few patients.

Tuesday, 30 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. I took Chaplain B. D. Mahedy into Tacloban in the rain as I wanted to meet with Brigadier General G. B. Denit to try and move nearer the combat area. USASOS has been moved to Leyte. Prostitution is good business here, the ‘street of joy’ had 12,800 GI customers last month, and the ‘Madam’ running the place and collecting half of the proceeds, netted herself 35,000 US dollars with no income tax to pay as the new Government have no one to collect any. The street is open from 0800 till 1200, and some of our boys begin to get in line at 0400 in the morning to be first.

Wednesday, 31 January 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. An attack transport came alongside and we loaded casualties until midnight and expect to leave some time tomorrow. The USS “Comfort” is back from the Zone of Interior.

Thursday, 1 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. The “Hope” left Leyte Island at 1400 hours with 692 patients not too badly wounded, and a great many medical cases. We just heard that one of the Japanese PW camps had been freed on Luzon (the great Cabanatuan Raid took place 30 January 1945 with 6th Ranger Infantry Battalion elements, Alamo Scouts, and Filipino guerrillas, successfully rescuing 489 prisoners of different nationalities –ed).

Friday, 2 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. One of my doctors and several Nurses have dengue fever. A few cases of malaria have developed among the patients.

Saturday, 3 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful day.

Sunday, 4 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. We now have six cases of malaria in all. Another uneventful day has gone by.

USS “Refuge” (AH-11), US Navy Hospital Ship at sea. After the Japanese surrender, the Hospital Ship went to Korea and China, taking up RAMPS, evacuees, and sick or injured troops, and brought them to Okinawa, in the Ryukyu Islands. After making another two trips to mainland China, she loaded troops and patients at Okinawa in October 1945 and set out for San Francisco, Zone of Interior. Her last trip consisted in picking up returning American troops in Japan. The “Refuge” returned to the United States and was subsequently decommissioned on 2 May 1946.

Monday, 5 February 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. We entered the harbor late in the evening and found several ships at anchor, among which some Hospital Ships. The USAHS “Emily H. M. Weder”, USAHS “Marigold”, and USS “Refuge” (AH-11) are ahead of us. The Captain got our small boat off before the “Hope” dropped anchor and he was back in only a few hours with forty five bags of mail. We will all have a big night and there will be little sleeping!

Tuesday, 6 February 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. I spent the day ashore and did a little trading for some projecting paper. I met Colonel Mudgett at Base “B” (27th Hospital Center –ed), and he told me they are going to send approximately a hundred tons of medical supplies to the front on our ship. He further said he expects this base to be closed by 15 February 1945. This is OK as the standard joke here is that all the Japs should be moved here after the war for punishment. All the rest of our delayed Christmas packages came with this mail, so we’re almost up-to-date on everything.

Wednesday, 7 February 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. Our patients were unloaded at the dock early this morning and we had to get away immediately as the troop transport S/S “Monterey” could come in and take on more troops. We had just dropped anchor again, when the “Monterey” blinked us that Major William V. Barney, my old Chaplain on the USAHS “Acadia” was aboard and whether I could come over and meet. We really had a grand session together, just like old times.

When I returned to our ship, I found we have 6 ARC workers and 4 doctors to take to Leyte.

Thursday, 8 February 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea, Pacific Ocean. We loaded supplies from a lighter. The port sent some stevedores who unloaded forty tons in six hours, we did the rest.

Friday, 9 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful day.

Saturday, 10 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. It rained all day. We passed the USS “Refuge” (AH-11) a day ahead of schedule. She must have broken down again.

Sunday, 11 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. Nothing but rain.

Ambulatory patients often slept on deck in the open, while others preferred to stay inside the wards. When overcrowded, the Hospital Ship’s crew and some of the boat’s medical complement sometimes gave up their bunks to the wounded men and went to sleep elsewhere.

Monday, 12 February 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. We dropped anchor at Red Beach shortly after daylight and at once received orders not to take in patients. Does this mean we’re going forward? I was ashore all day in the mud and rain, but the news I collected is excellent. We are leaving for Luzon and will take a first group of Nurses by ship to that area. We will also be the first American Hospital Ship to move into this zone. Another sixty tons of hospital supplies were taken on board today.

Tuesday, 13 February 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. We received our orders and will sail tomorrow for Subic Bay, Philippines. I just hope they don’t change the plans. We tried to enter Tacloban dock late this afternoon but the tide was too swift so we are now anchored in the channel and will try tomorrow at ebb. I was talking to an Army Air Force patient in one of the wards with a broken back from a plane crash. He described how his aircraft was flying low over enemy territory and how it was shot down in flames. He managed to crawl out of the plane and got rescued by some local guerrillas. The pilot was killed. I didn’t think much about it until later when I was conversing with a lad who suffered a broken leg in another ward he described the same sort of incident so vividly that I took him to see the boy with the broken back and sure enough, they had been in the same plane and had reported each other as dead! Maybe more of the missing will turn up this way some day. We took on 246 Nurses from the 30th Evacuation, 36th Evacuation, 3d Field, 120th General, and the 227th and 251st Station Hospitals.

Wednesday, 14 February 1945: Leyte Island, Surigao Strait, Philippines. We made the Tacloban dock just as the tide was changing about noon, and took on twenty-eight truckloads of Nurses’ baggage. Nurses who had been captured by the Japs and held prisoner on Luzon were flown down to Leyte this morning and I managed to talk to some of them. They had not been molested by the enemy but had been forced to work long hours in the Manila Hospital taking care of Americans and civilians there. The food contained in American Red Cross packages was denuded of all chocolate, sweets, and some other items before it was given to them after their liberation, as they were all very much undernourished with many being sick and very weak. The American PWs on the other hand had really been badly treated. Many had been shot for minor offenses.

We left port at 1700 and crossed Surigao Strait in the dark. Lieutenant Stephany, my former Dietitian from the USAH “Acadia” is on board as a passenger. She now serves with the 120th General Hospital.

Thursday, 15 February 1945: Mindanao Sea, Sulu Sea, Philippines. We’re having a beautiful trip through the Philippine Islands as we are close to shore all the way and the weather has been wonderful to us.

Friday, 16 February 1945: China Sea, Corregidor Island, Philippines. We were standing off the island of Corregidor watching what we thought was a large flight of cargo planes with their fighter escorts, when suddenly part of the sky was filled with paratroops and the assault on Corregidor was begun (capture of “The Rock” lasted from 16 February until 2 March 1945 –ed). I can see that we won’t reach Lingayen Gulf for some time and then will probably be filled with patients. I found a horseshoe just before leaving Tacloban. It must be a sign of good fortune for someone. It looks as though we are in the right place at the right time. We didn’t stay off shore very long and came up the coast a few miles to Subic Bay and reported to the Admiral in command of the Fleet. We hadn’t been ordered here, so we weren’t expected, but they were grateful to see us as the only means the Medical Officer in command had to rely on was a couple of LSTs (H), and they certainly weren’t expected to handle the fighting on Bataan and “The Rock” by themselves. Furthermore, the area was almost entirely out of medical supplies and we were the only ones to fill their needs. With 250 beds taken up by our 246 ANC passengers we had to make immediate adjustments. These girls were very cooperative and most of them willingly moved their beds out on the deck and helped prepare our wards for the wounded to come. We managed to debark 150 Nurses destined for an Army Hospital, and took on 574 wounded.

Subic Bay is a beautiful sight, almost landlocked by a small island at the entrance and with forest covered shores rising gradually into the hills. As the “Hope” entered the bay, we found it heavily guarded by some cruisers and the area filled with only fighting ships, except for a few freighters. We took on the first wounded around 1800 hours and a great many of them were burn cases. We haven’t gotten any airborne personnel yet, and probably won’t till late at night or early the next morning. Most of the cases on board are from the Navy.

Saturday, 17 February 1945: Subic Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines. We started loading again at daylight and most of the wounded were paratroops, either shot down while landing or injured by rocks, debris, and the rugged surroundings, created by constant bombing of the island’s surface. Together with the airborne troopers, we received infantry and Filipino guerrillas from the Bataan area, and even a two-year old baby boy lightly wounded. The boy’s father was with him, pretty badly shot up. Colonel Lucius Patterson, the area Surgeon came aboard this afternoon and told me about the harsh fighting in downtown Manila and the many fires. He took the Nurses for the 36th Evacuation, the 3d Field, and 227th Station Hospitals with him. This gives us some more bed space.

Sunday, 18 February 1945: Subic Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines. We took on the survivors of an LCS that had been hit by a Japanese suicide boat. We usually get a lot of news from the wounded. This last bunch told us that many Japanese had been driven into dugouts and caves underground, but that a lot of fierce fighting was still to be expected on Corregidor Island. We operated on the father of the baby and removed part of a 20mm shell from his foot. These guerrilla fighters are a tough bunch, they just lie there and don’t even whimper. The baby is getting badly spoiled. At night he crawls out of the box that serves as a cradle and is taken in bed by one of the soldiers. Our tailor made him a little uniform and the rest of my boys stuff him with candy. One of our belly cases died and a burn case also. Another patient is a survivor of the “Death March” of Bataan and he says that none of the horror stories is as horrible as the actual thing. This man successfully escaped and was aided by some local guerrillas who took him to the hills and freedom.

Monday, 19 February 1945: Subic Bay, Luzon Island, Philippines. We took aboard some of the wounded who had been trapped on “The Rock”. There are about 300 of them. The group has filled our extra mess hall and the available deck space on the ship. We will sail tonight and with a little luck should reach Lingayen Gulf sometime Tuesday morning. We went over to the S/S “Blue Ridge” and got permission to get food from a supply ship that just came in; forty tons of it.

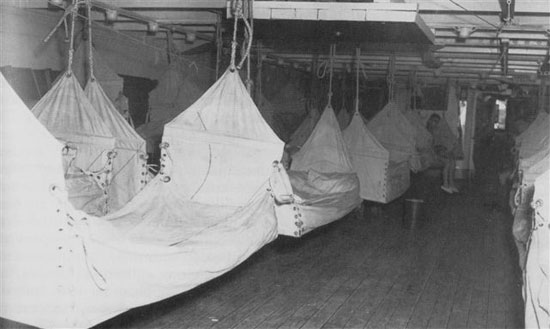

Wicker baskets for the dead are stored in tiers in a US Navy Hospital Ship. They are exclusively used for storage and not for burial ceremonies.

Tuesday, 20 February 1945: Lingayen Gulf, South China Sea, Philippines. We pulled into the place early in the morning but were unable to take all the patients because of lack of space. Only the critically wounded were accepted. The rest of the Nurses and doctors were sent ashore under a heavy barrage of shore guns. During the night there were two enemy air raids, one of which destroyed a gasoline dump nearby which shook our ship pretty well. These are the first Jap planes we’ve see since the invasion of Luzon.

Wednesday, 21 February 1945: Lingayen Gulf, Philippines. We took on only 147 wounded today as we have no more room. Our total is 720. The fire in the hills from the enemy air raids was still visible.

Thursday, 22 February 1945: Mindoro Strait, Philippines. We buried a soldier and a sailor at sea today and performed four amputations. I received orders not to stop at Leyte but to return to Hollandia, New Guinea. One of the patients was telling me how some Japs would tie explosives around their waists and then run on to our ammo dumps or positions and blow them up. Our snipers would try and spot them and shoot at their middle, and if hit they would simply disintegrate.

Friday, 23 February 1945: Sulu Sea, Philippines. We are gradually catching up with our fractures and operations. Two more belly wounds died during the night. Nearly all the belly wounds that have been operated on in the field die of peritonitis. Our poor little x-ray department is taking a beating and has been running day and night.

Saturday, 24 February 1945: Celebes Sea, Pacific Ocean, Philippines. We buried two more patients today.

Sunday, 25 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. We slowed down to ten knots as the weather is so rough we can’t work in such conditions and our patients are suffering. Three cases of pneumonia have developed.

Monday, 26 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. We have saved what’s left of a Filipino family on board. They were members of a guerrilla band escaping Bataan and the fighting there in an outrigger canoe. When they approached some of our landing craft they didn’t answer the challenge and a 20mm gun aboard an LST opened fire blowing the canoe out of the water. The mother, one older boy, and four younger brothers were wounded. These people have a lot of fortitude as they haven’t complained a bit and silently endure their pain while being treated.

View inside a US Navy Hospital Ship (ward under deck) fitted with extra hanging cots in case of overflow of patients. The individual condition of the evacuee always prevailed and it was up to the medical personnel to check whether he was able to make use of this solution.

Tuesday, 27 February 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful day.

Wednesday, 28 February 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. I found I had thirteen letters from home! We arrived this morning and were called at the pier at 1730. Among the debarking passengers was a medical Officer who had been a prisoner of war on Luzon for three years. A week before the assault on Luzon Island, all the American Officers above the grade of Major were sent by ship to Formosa or Japan. He said that the Japs were not only lacking food but were so short of medical supplies that many times PWs were compelled to form details to go on expeditions. All these ex-PWs are going home on the S/S “Monterey” troopship. They will be escorted by Chaplain W. V. Barney.

Thursday, 1 March 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea. We loaded medical supplies all night. It’s hot as hell here and the place is infested with mosquitoes.

Friday, 2 March 1945: Hollandia, Humboldt Bay, Netherlands New Guinea, Pacific Ocean. We unloaded all our wounded in good time and are leaving for the Philippines. We have been battling bedbugs and other insects and found that the boys were bringing them in with souvenirs they have been buying from the natives. DDT cleaned them up quickly.

Saturday, 3 March 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful day.

Sunday, 4 March 1945: Pacific Ocean. We’re returning to Leyte in the Philippines. Nothing to report.

Monday, 5 March 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. We arrived this morning and came right into the dock where we loaded 762 patients. They were mostly old cases and eightballs (misfits –ed) being sent out to free bed space for the most recently wounded. Colonel Dart tells me that there are over 3,000 hospital cases ready to return to duty and he can’t get the orders to send them back. They’re needlessly taking beds that are badly needed. I received a message from an LST and in the evening Sergeant Benny Levin, one of the boys in my pharmacy at Monmouth came aboard and we had supper together. He has been serving in the Pacific for nearly three years. Major A. Weiss has finally gone back to the ZI on rotation. Colonel Taylor came aboard for lunch and told us that the “Hope” was being loaned to the Fifth US Fleet (established 26 April 1945 to operate in the Central Pacific –ed) for the next invasion after we leave our present load in New Guinea. We will first go to Ulithi Atoll and wait for orders there.

Tuesday, 6 March 1945: Leyte Island, Philippines. Just as we pulled out from the dock, we learned that our orders were changed to Finschhafen, New Guinea. It seems that all the available hospital beds in Hollandia are filled. As we are half way out the channel, one of our NP patients decides to jump overboard with his clothes on including his boots. We put our motor launch over at once but it took some twenty minutes before he was rescued, none the worse for the experience as the water is very warm. Another neuro-psychotic patient whom we brought back from Manila is obsessed with food. Besides eating three trays of hot food, he would go around snatching food from other trays and even stealing from the garbage cans. These boys were just skin and bones when taken aboard. Many of them suffer from beri-beri.

A motor launch brings out casualties to a US Navy Hospital Ship. They will be taken on board, examined, and only then assigned to the proper ward. The procedure can be modified depending on the patient’s condition, if critical, he will receive the necessary priority and immediate care.

Wednesday, 7 March 1945: Pacific Ocean. Most of the Hospital Ships will go and serve with the Fifth Fleet and our best bet is that our destination will be the East China Sea or the small group of islands south of Japan. We are to be at Ulithi not later than 20 March.

Tursday, 8 March, Friday, 9 March, and Saturday, 10 March 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful days. None of the patients needs special care. It’s a shame to bring them back so far behind the lines, when most of them will inevitably be returned.

Sunday, 11 March 1945: Pacific Ocean. A lone transport plane flew over the ship today with 12 fighter planes as an escort, this could have been Eleanor Roosevelt, the First Lady (on a tour of American bases in the region).

Monday, 12 March 1945: Finschhafen, Netherlands New Guinea. Colonel Earl Wood of the 119th Station Hospital met me at the dock. Our pier is right near a large air base. A call has been sent out for all Russian-speaking Americans to report to Headquarters (on 3 February 1945, the Soviet Government agreed to enter the Pacific conflict after the war in Europe would be over –ed). I visited most of the twelve hospitals here but most of them are about empty, as we’re closing over the harbor and its area and turning them over to the Aussies.

Tuesday, 13 March 1945: Finschhafen, Netherlands New Guinea. I took some time to explore the area. The heat was oppressive, but as we entered the jungle from the bright sunlight to the deep shade it was just like walking into a Turkish bath. We had to travel fully clothed from head to foot because of the numerous insects, and had smeared our bodies with repellent oil. The scenery was extremely beautiful and the coloring breathtaking. The natives we met were friendly and some of them spoke pidgin English.

Wednesday, 14 March 1945: Finschhafen, Netherlands New Guinea. Today I spent some hours on the coral reefs hunting for shells that the locals use as money. The coral is very sharp and we had to wear gloves; it certainly was a lot of fun but also back-breaking. We went into the hills and picked a lot of paw-paws for the ship’s mess, and they were delicious when cold and served with fresh lime juice. From the hills we visited the old Christian Missionary cemetery (German Lutheran). Some of the older natives can still speak a little German.

Thursday, 15 March 1945: Finschhafen, Netherlands New Guinea. The hairdresser (the only one in Finschhafen) came down from the camp today and did eighteen permanents in six hours, making some of our Nurses not only beautiful but also very happy. He was formerly with Saks, Fifth Avenue in New York, and is now a buck private in the Army.

We loaded medical supplies in the morning and sailed out of the channel at about 1500 hours, and went alongside an oiler to fill our tanks. We then took off for Manus Island.

Friday, 16 March 1945: Manus Island, Admiralty Islands Group. As we pulled out of New Guinea we ran into a small typhoon and were swept about twenty-five miles off our course. Nevertheless, we reached Manus in the late afternoon. There was a British fleet in the harbor. 4 battleships, 11 cruisers, 18 aircraft carriers, destroyers, many smaller warships and HMHS “Oxfordshire” which we met so many times in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean (part of the British Pacific Fleet, loaned to the US Navy for service with the Fifth United States Fleet –ed). Here we acquired a new flat boat that we can now use for transferring patients and loading supplies. This new operation must be pretty big with the British joining us (TF 113 left Sydney, Australia for Manus Island forward base and included British, Canadian, Australian, and New Zealand ships –ed). Our pilot in Manus is a Scot who has spent the greater part of his life in New Guinea looking for gold and bragging what a wonderful place Great Britain is. He hasn’t been there for forty years.

Saturday, 17 March, Sunday 18 March, Monday, 19 March 1945: Pacific Ocean. Uneventful days.

US Navy aircraft carriers at anchor at Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands, 8 December 1944. The wide lagoon was used as a major anchorage and staging area (larger than Pearl Harbor) for operations against the Philippines, Formosa, and Okinawa.

Tuesday, 20 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. Our first intimation that we were nearing the place was the sighting of the American fleet. They pulled into the anchorage area just ahead of us. The highest point of land on this atoll is only eight feet so the first silhouettes were the warships. Their masts completely obscured the tiny drops of land around the great coral reef that encloses the lagoon which extends for eighteen miles in one direction. It is ten miles wide at its greatest point and two at the narrowest. When going for anchor we found ourselves along with 7 other Hospital Ships in the midst of this large fleet of warships. There are no troopships as far as I can see, only heavies! We must be going to hit near one of the main Japanese islands, I think.

Wednesday, 21 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. The American battle fleet left this morning. The Captain and I visited the USS “Comfort” (AH-6) this morning. We have a flattop anchored near our ship with a gaping hole in her aft deck where a dive bomber hit her a few days ago. It was a tragedy as most of the crew were watching a movie when she was hit. All afternoon, an enormous convoy of attack transports has been filing into the area. They carry Marines and we’re told there must be thousands of them (invasion forces consisted of 81,000 Marine Corps and 102,000 Army troops –ed). The next island assault will be terrible. We’re going to Okinawa about three hundred miles south of Kyushu, Japan. As there are three large airfields on the island it must be heavily protected.

Thursday, 22 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. I watched the morning sun silhouette some of this great fleet and wonder how many more sunrises some of the kids will see. The Skipper and I paid our duty call on the Admiral but he was too busy to see us. We received more mail from home today.

Friday, 23 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. The British battle fleet took off this afternoon together with some of the smaller ships.

Saturday, 24 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. We moved anchorage for the fourth time to make room for more ships coming into the harbor. The aircraft carrier USS “Randolph” (CV-15) was there, hit by a kamikaze plane 11 March 1945, which penetrated Ulithi harbor and crashed on her flight deck, killing 27 (after repairs she would be ready to support the Okinawa Task Force on 7 April 1945 –ed). Later the USS “Franklin” (CV-13) came in with two other of the large flattops. They blinked us to take their wounded, but we couldn’t as we are alerted to move out any time now. The USS “Bountiful” (AH-9) and the USS “Relief” (AH-1) are the ‘station’ Hospital Ships for the area. The aircraft carrier had 990 crew members killed and wounded after being hit by 2 enemy bombs during a fighter sweep fifty miles off the Japanese mainland on 19 March 1945. The ship will be out of the fight for a long time; the boys who survived are a lucky bunch for sure (she was patched up at Ulithi atoll, steamed out on her own power for Pearl Harbor, and subsequently returned via the Panama Canal to Brooklyn, NY, for definitive repairs –ed). I got three letters today. I went into the Beach Officers’ Club and met Ernie Pyle (war correspondent) and had dinner with him. The last time I saw him was in Italy. The boys all think a great deal of him and he has a lot of guts. Jack Dempsey (former heavyweight champion) was also over here as an Officer with the US Coast Guard, serving on the USS “Arthur Middleton” (APA-25), going around and shaking hands. Ernie Pyle always goes in with the assault waves and sticks with the men in their foxholes. There’s a striking contrast between the two men as Ernie looks almost emaciated and very nervous, while Jack is heavily built and prosperous looking.

US Navy Hospital Ship “Relief” (AH-1), on its way to Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands, 13 March 1945. After duly participating in many operations in the Pacific Theater such as the Gilberts, Marshalls, Marianas, and Western Carolinas, she went to Okinawa evacuating nearly 2,000 wounded to Guam and Saipan. With the war over in the Pacific, the “Relief” next mission was the evacuation of RAMPs from Manchuria, followed by more missions in China, in Okinawa, and Guam, before heading for home. The Hospital Ship almost evacuated 10,000 patients from combat areas and was decommissioned on 11 June 1946.

Sunday, 25 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. Some of the smaller assault ships left today. There are 900 of them in this area, including the British fleet (designated TF 57) which arrived today from Manus Island, an awesome sight!

Monday, 26 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. Five letters arrived today. We are doing much better with this fleet. Each night we have an alert when a Japanese plane makes a scheduled run over the area to take photos. They’re getting an eyeful and must become plenty worried. The large battle fleet has now gone and is supposed to start pasting Okinawa in preparation for the assault early April. We have movies on deck every night and only stop during an air alert or raid. It has rained so heavily every day that we all go about in ponchos and hats and sit it out in the downpour.

Tuesday, 27 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. The LSTs have pulled out this morning and the attack transports left in the afternoon. The atoll begins to look deserted. The “Hope” should also be on her way in a couple of days as we run alone and can get there much faster than the other ships. There are only three of the aicraft carriers left here and a single supply ship. This doesn’t mean that the harbor itself is empty as there are hundreds of cargo ships and freighters waiting to take off as soon as the anchorage at Okinawa is secure enough.

Wednesday, 28 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. It still is raining hard and quite a wind is blowing.

Thursday, 29 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. Several of us took off in a landing craft for the beach and I was to be dropped together with Technician 4th Grade Curtis Lewis on an island inhabited by natives. We hadn’t left the “Hope” an hour or so, when a terrible wind hit us and we soon were in the midst of a local typhoon. Half the time the barge was under water or almost flying through the air. Some of the men were very sick and the rest of us rightly scared. The storm lasted over twenty-four hours but to us seemed like a year.

Friday, 30 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. The typhoon stopped as suddenly as it started and we soon reached the island. About a mile off shore, we had to row in the rest of the way because of Japanese mines. When we visited the local village, we were told that the enemy had removed all the young males to another island. The old chief we met conversed in pidgin Japanese and broken English. The locals had been christianized by Catholic missionaries with many of them wearing small crucifixes.

Late in the evening ARC workers came aboard carrying 2,240 pints of whole blood that had been flown in from the States in special containers.

Saturday, 31 March 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. We are still at anchor and are waiting to be called into a beachhead area. The assault against Okinawa starts in the morning.

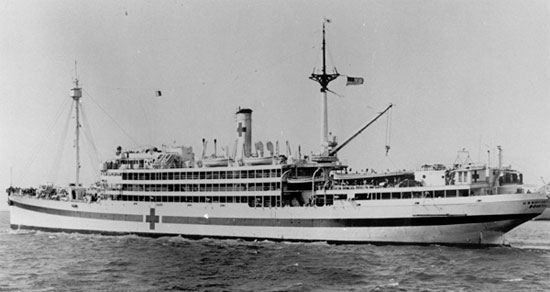

Partial view of the USS “Hope” while sailing in convoy in the South Pacific. Courtesy Robert C. Semler.

Sunday, 1 April 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands. It is Easter morning and we are informed that the invasion started (Operation “Iceberg” 1 April 1945 –ed) and the landings were practically unopposed. The main enemy airfield was captured in less than two hours. If there are wounded, they must be flying them out as we haven’t been called in to help.

Monday, 2 April 1945 throughout Thursday, 12 April 1945: Ulithi Atoll, Caroline Islands, Pacific Ocean. The “Hope” is just sitting around waiting for orders. We have heard that there has been very little fighting up to date. 3 Officers and 26 EM from the 54th Portable Surgical Hospital have been transferred to us from the USS “Mercy” (AH-8) on Thursday. We are to take them with us. On 9 April we were ordered to leave the fleet anchorage at Ulithi and sail for Okinawa in company of the USS “Samaritan” (AH-10)

Friday, 13 April 1945: Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands. After sailing around so many days without action, we were finally called into Orange Beach Two, behind a string of mine sweeps and down a long line of warships that were continually firing at the enemy installations. 125 aircraft were shot down during the day but there seems to be very little activity on the shore proper. We received notice of President D. F. Roosevelt’s death but it caused very little disturbance as we were otherwise occupied. I managed to go ashore for a few hours as the old 104th Engineer Combat Battalion is on the beach but I unfortunately couldn’t contact them. As the enemy shelling got pretty bad I returned to the ship. A hidden 75mm enemy gun on the beach has been firing our way but only nine of the shells came near enough to get excited. By evening the fighting got worse inland and the sky over that area was filled with star shells. We usually leave the combat area at night, and return to the beach area in the morning.

Okinawa, Ryukyu Islands, 13 April 1945. Supplies and equipment are offloaded at one of the invasion beaches.