Veteran’s Testimony – Elinor Warner Bird 203d General Hospital

Introduction:

The following narrative (except for this introduction) was written by Elinor Warner BIRD who was a Nurse with the 203d General Hospital. Before her death in the early eighties, Elinor sent this copy of an account of her career as a civilian Nurse and, later, her career in the Army Nurse Corps. It is the portion of this narrative, called “A Trip across the Sea”, which concerns her association with the 203d that is of interest to the readers of this anthology.

Service in the Zone of Interior (ZI):

An aerial view showing Camp Haan, the place of enlistment into the 203d General Hospital for Elinor.

Photo courtesy of the California State Military Museum.

Briefly, the account of Elinor’s beginning history starts in the years 1933-1934, the years of the Chicago World’s Fair. She was there, taking a post-graduate course at Cook County Hospital, ‘the largest hospital under one roof, in the world’. Elinor says she was able to attend the Fair and on one occasion, she had her fortune told. For a dollar, the man looked at her hand and then said, “You are going to take a trip across the sea and have lots of money.” Says Elinor ‘Little did I ever dream that any part of it would come true. But the trip did in 1943, but as for the money, I am still waiting for it’.

After completing her post graduate course, Elinor Warner Bird entered the Indian Service and was sent to Onigum, Minnesota which was a TB Sanatorium that at one time was a Boarding School. Here she encountered an initiating experience of a fire in the Sanatorium during a winter season which boasted temperatures far below the zero mark. A new Sanatorium was subsequently built, but Elinor and the Chief Nurse were transferred to a small General Hospital and later moved again to a new General Hospital at Red Lake. She enjoyed a pleasant two years here before being transferred to the Indian School at Chemawa, Oregon – ‘an ideal spot located only 4 miles from Salem (Oregon)’.

Elinor was enjoying her job at Chemawa when World War 2 broke out on Sunday, December 7, 1941. A staff Physician suggested she join the Army and she followed his advice. In September 1943 she received orders to report to Camp Haan, Riverside, California which housed an Antiaircraft Artillery Training Center.

It is from this point that we will join Elinor’s own narrative about her experiences with Army life and the 203d General Hospital …

At Camp Haan, there were many Nurses awaiting orders to move overseas. No one knew the name or number of the unit to which they belonged and we were no exception. Most of those Nurses had been activated at Fort Lewis, Tacoma, Washington (Army Ground Forces Training Camp). These Nurses arrived the same time as I did, and we received order to report to Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey (Staging Area for New York Port of Embarkation) the first part of December.

In crossing the country by train, our uniforms invoked a great deal of curiosity. We were joined by two other Nurses who were also going to Camp Kilmer. We left the train at Harrisburg, Pennsylvania and then took a local train to New Brunswick, New Jersey where we were met by two enlisted men driving a pickup truck. The ride to Camp Kilmer was a twenty mile jaunt through a cold rain which did not uplift our spirits. It was here for the first time that we found we now were part of the 203d General Hospital which was later to be one of the largest, if not the largest medical Hospital unit going overseas.

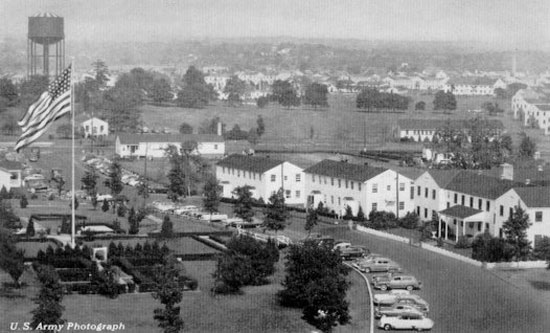

US Army Photograph showing Camp Kilmer. Photograph has been taken post-WW2 (identified by the 50-star American flag which hangs on the left hand side of the picture).

Later we were joined by two more Nurses, also from Camp Haan and our Chief Nurse joined us still later. She wanted to go to the South Pacific, but was doomed to be disappointed, much to our regret.

Christmas Day, 1943, was spent in preparing for movement overseas. Our Blue Uniforms had been replaced by Olive Drab, our White Uniforms replaced by Brown and White cotton Seersuckers which were one piece and fastened like a bathrobe. Everything else had been or had to be sent home. Our Capes were of Olive Drab material. We were issued Class A Uniforms which consisted of a Suit (2), Shirts, Skirts, Neckties, Russet Brown Oxford Shoes and Gloves. The Cap had a large eagle on the front. We had Rayon Stockings, a Service Gas Mask, which was worn over the shoulder, a Pistol Belt to which was attached our Canteen and a Mess Kit. The latter consisted of two parts, inner and outer container, and furthermore a Canteen, Cup, Knife, Fork and Spoon. We carried water in the Canteen.

The Musette Bag which we carried on our backs would hold 40 pounds and we packed it to capacity. We had a footlocker, which was a ‘must’, where we put some things that we would not be using for some time. We had bedrolls that held two blankets and other things. It had what you would call a hood, for when we were camped this would hang over the head of our cot and the rest of the bedroll served as a mattress. We were issued a Red Cross pin which was the only pin you were supposed to wear. Our bedrolls were rolled by our enlisted men as our Commanding Officer did not think it proper that women should do this.

Preparation for Movement Overseas (POM):

It was a busy Christmas Day. After completing more trip preparations, we boarded a train. We had a lunch that had been packed for us at Camp Kilmer. Then we boarded a ferry for the pier in New York Harbor. This was the first time I had ever been on one. We were lined up in alphabetical order for the first time; but we got used to it in the future. While we were lined up to board ship, the Red Cross served us coffee and doughnuts which tasted good as we had been traveling for sometime. Then we assumed the ‘order’ again and boarded the ship. We had had a long day with lots of waiting. The weather was somewhat damp and the sky overcast. It was December 28, 1943.

We had nine bunks to a cabin, three rows and three in a tier. That night we went up on deck to see the last of New York for sometime. We had hopes of seeing the Statue of Liberty, but it was too dark. The lights of the city were on although we couldn’t see anything.

Upon awakening the next morning we were told we had to carry and wear our ‘lifebelts’ all the time. We could dress informally in the mornings, but for the evenings we had to wear Class A Uniforms. We had only two meals a day, and we had no place to sit in our cabins so after breakfast, whenever allowed, we would go up on deck. We were well supplied with candy. Our boat was the South American Liner ‘Brazil’. We learned that we were part of a large convoy and it was supposed to be the largest up to that time. To our starboard side was the sister ship, ‘Argentina’. Later, after getting out of the service I met a dietitian from that ship. During that night and several times afterwards, ships joined our convoy making it even larger.

We were fortunate in having nice weather during the day, but it rained every night. We had no place to sit in our cabins other than our bunks, and we could not go out on deck after dark. Guards were posted, and we would have been turned back if we tried, besides taking our names to be reported. Each cabin had a CQ (Charge of Quarters) and I was ours. Guards were stationed outside and if we were not in by a certain time we were reported. The girls in our cabin never were. But one night the Assistant Chief Nurse made rounds unexpectedly, and she found one or two girls missing. We tried covering up for them as we were supposed to report them.

Three nurses of the 203d Gen. Hosp. prepare for movements overseas. Note that all three wear the Winter Combat Jacket (“Tanker” jacket). This photograph was taken in England prior to the unit’s embarkation to Normandy, 1944.

Our trip was uneventful. Rumors floated around that we had sunk a ship or we had lost one, but no truth was attached to the rumors. One day one of my cabin mates was leaning out of the porthole when men began target practice. She practically fell back into the cabin. Some of the girls were quite seasick too. They would go to the dining room but the smell of the cooking bothered them so they would turn back. I was fortunate in not getting ill as this was my very first trip on a boat.

At dinner each evening they announced that we should set our watches ahead from a half hour to an hour at midnight. They repeated warnings about no lights. Each day we had boat drills, and after looking over the side, I hoped we would never have to take to the small boats in case of emergency!

England

After a pleasant trip and in spite of many hazards, we reached the Firth of Clyde in Scotland. We stayed on board for five days here. Among the units on board was the 13th Transportation Battalion , which was destined to cross our paths many times. Everyone admired the scenery we viewed, each thinking it resembled the part of the country they had come from. There were boats of all descriptions, including fireboats. Some units left and those who remained had to double up in their eating times. I always had more than I could eat and would take the extra food back to my sick cabin mates. Others did it too, and they appreciated it.

Upon leaving shipboard, we boarded a train which left from the docks. We went down through Scotland. It was supposed to be a secret who we were, but the sidewalks and roofs of houses were crowded with people waving American flags. We finally arrived in England at the small town of Petworth. We were taken by trucks to Base Camp which was five miles from town. This was a Canadian camp, having been built by them. The 48th General Hospital was stationed below us, and we encountered them again after we left there.

The barracks were of Nissen hut construction. We slept in large rooms with a coal stove at each end. The enlisted men kept us supplied with coal, and we would get up in the morning to build the fire. Here we made good use of the blankets that were issued to us. They certainly came in handy for we had no other covers. We had road marches because we had been on shipboard for so long. Many a Nurse had to be brought back by Ambulance as she fell by the wayside.

This town, i.e. Petworth, was rich in history. One morning we went into town early and found all the shops being opened by a man dressed in a coat with a cape and a large brimmed hat. After this we thought surely we would meet the town crier as he was a typical character from Charles Dickens’ books. We were here for a month, taking daily road marches, always dressed in fatigues and wearing leggings and helmet liners. We did get to see something of the town and went through a Cathedral which was extremely cold. Noted people were buried here. Some of the names were names from both sides of my family. I was surprised to see some of my mother’s family as I thought they were buried in Scotland, but I was told it was a common name around here.

From the Cathedral we went sightseeing to Chichester and for lack of something to do, we went to a movie, or cinema, and saw ‘Robin Hood’ for the third time. While at the movie we heard the air raid signal and guns firing at the edge of town.

We never had to walk the five miles to Petworth, for someone would always come along and give us a ride.

We then left Petworth for Swindon We became quite adept at climbing into the trucks when moving around.

As our names were called, homes where we were to be billeted were indicated, and we detrucked. When I reached my destination, the woman answering the door was asked if she knew my name. She replied “Yes, it’s Elinor”. I found out that she had chosen me for my name. At first she was not going to take anyone in as she had had one son shot down over Greece and the other was somewhere in the Army, and stationed in England.

Riding in style! Nurses of the 203d commandeer a Jeep in the Marshalling Area during the unit’s short period in Winchester, England.

I was very pleasantly situated here. The landlady would go to bed before I did and would put a metal hot water bottle in my bed besides lighting the gas heater. We would sit beside the fireplace at night reading and listening to the radio. After the news and Big Ben had tolled 10 p.m., we would go to bed. And I was always welcome to bring in my friends. She loved to play cards and would play for money and she always won!

Our baths were limited as was the hot water so I would use the water from the hotwater bottle to wash in the morning. They were afraid to use much water as they feared they might need it for fires set by bombs.

We left Swindon for Burford, on March 15, 1944. It had been very cold when we were in Swindon, the coldest period they had had for some time, and they actually seemed to blame us for it.

We set up our Hospital in Burford in part of an old estate. We had nice quarters, eight to a cabin, but our toilet facilities were outside. The wards were set up, and I set up the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat ward (EENT). The enlisted men took huge bundles of blankets and polished the floors. The wards had three stoves in them, and many a night during an air raid alarm when we had to go to the Hospital, we were glad for the heat. If anyone failed to get up for an air raid alert, the MPs aroused us. One night after an alarm, as we were going back to our quarters, we saw the planes coming back in formation. One woman said once she used to see them go out in the morning and would count them and could tell how many were missing when she saw them come back. When an alarm sounded at night, we would don our fatigues over our pajamas. We had to carry our gas masks in an alert position over our left shoulder. Our attire included our field coat, leggings, shoes and steel helmets.

Burford was in interesting country. It was in the heart of sheep country. It was here that we saw our first roadblock – a kind of barricade consisting of a tree stationary at one end with the other end on wheels to roll across the road when necessary.

On our days off we went to visit various places of interest. In Bristol, there was a post office designed by an American architect. There was also a suspension bridge which I had no desire to cross after reading of the one in Washington State that collapsed. There had also been some bombing in Bristol, and on one street the Germans had bombed all the churches. Many bridges were propped up. And one day we went to a pantomime called “Cinderella” and the leading male part was taken by a woman which was common in these times of war.

We saw Bath, built B.C., where the Roman baths and the pump houses were located. The baths were supposed to have a medicinal purpose and were pumped to London. There was also a large Cathedral, which had a Jacobs’ Ladder. At one time it was believed that by climbing it you would reach heaven. Here, again, inside this Cathedral I found similar family names.

In London we saw what we could in spite of gas rationing. Westminster Abbey was all boarded up, whether the windows were already out or this was done to save them, I didn’t know at the time. We saw Big Ben Clock, St. Paul’s Cathedral where so many famous weddings took place. There was Buckingham Palace where in peace time the changing of the guard is very colorful. We visited Madame Toussaud’s Museum, a noted place where all the figures were made of wax. There were many of our statesmen in this Museum, the Royal Family, and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. The latter were set apart from the others as if they might contaminate the rest of the Royals. All the shops we visited in London had stone floors and the women got down on their knees to scrub them.

Another time we went to Stratford-on-Avon, Shakespeare’s home. It was on a Sunday and a beautiful day. We traveled the distance of 40 miles by truck. We saw his home and garden but were unable to go inside the house, which they said was empty, anyway. From there on we went to Anne Hathaway’s home. Here we could go inside. It had been in her family for generations. The roof was thatched as a great many were which we noted as we went along. Upon entering one was struck with the beauty of it. There were heavy black oak beams. To the right was the kitchen and the storerooms on the left. The kitchen and dining room were combined. In front of the fireplace was a long-handled shovel which was used to bake bread with. Hanging on the walls were copper kettles which were so polished that you could see your reflection. On the walls were also racks of dishes, first the flatware with one side hollowed out; next, the pewter ware and then lovely willow ware. There were jugs which rested on their shoulders to drink from. They utilized everything. There was a loveseat that they said was used when Shakespeare courted Anne Hathaway. Upstairs we entered her parents’ room. There was a lovely four-posted bed with a grass mat on it for a mattress and chests which were part of her mother’s dowry. The daughter’s room opened off from the parents’ room as they thought they might steal out at night! The boys had a back room which led to the kitchen.

We went to the Church where Shakespeare lay buried. His tomb was roped off. They said this Church had been remodeled three different times – in 1600, 1700 and 1900. The grave is always covered with flowers.

Later, we saw ‘As You Like It’ at the Memorial Theater. All these historical buildings etc. are now owned by the Shakespeare Foundation. Then we returned to Burford late in the evening and wondered how in the world the men were able to drive on the left side of the road with dim lights.

A large group of 203d Nurses gather in the doorway of their billet in Winchester, England. As can be seen, they wear a plethora of uniforms and headgear.

We left England on July 20, 1944, having turned our Hospital over to a newly formed unit, composed of some of our Nurses and some from other units, but the Officers and the enlisted men came directly from the States. We boarded the train for Exeter, some distance away and arrived there much later. A mixup occurred and some of us landed at a Naval Base. Later our Executive Officer came for us and we were taken to Thompson (Topsham) Barracks. This was an old English Army Post and the buildings were made of brick. Our beds were in tiers of three and they were very clean. We furnished our own bed linen. We were warned we might have to get up in the middle of the night to board ship. We would have quite a distance to go if this became necessary. We spent five days here and went on daily road marches. Each time we marched the roads, the sidewalks were lined with people. I am sure they had never seen women dressed as we were. We had our combat suits on which were warm.

France

We left Exeter in a rainstorm after receiving orders to depart for Southampton. Our bedrolls were prepared as usual, and we departed in Army trucks. Southampton was another old English Post which had numerous buildings. One of those was assigned to us. Once there, we had to sleep on cots with straw mattresses which we called ‘biscuits’ as they would always come apart.

Again we were warned that we might have to get up in the middle of the night to board ship, or in case of an air raid we might have to go outside and dig a foxhole, something I was glad we didn’t have to do.

On the first night in the new camp, we were awakened by the air raid signal. We all crawled under our cots for protection. I lay there shivering, whether from fright or cold, I don’t remember, but finally I decided if a bomb was going to get me it would get me if I were under the cot just as easy as if I were in it.

In the dining room there were signs posted ‘Don’t Throw Swill on the Floor’. We spent a week here being entertained daily by the Scots with their bagpipes.

1st. Lt. Wilmer Putt demonstrates her bagpipe skills, obtained during her stay with the various Scots on the continent! Note how she wears the one-piece HBT suit, along with a standard M1 Fibre Liner.

When we departed this time for the boat, we wore combat suits in addition to our overcoats and other equipment. The combat suits were like coveralls. After a ride of a considerable distance, we reached the harbor area. In passing through some towns, we were given fresh fruit by the local people. When we reached the port and while waiting to get aboard our ship, we were issued vomiting bags made of waxed paper, lice powder, seasickness tablets and extra rations.

The ship we boarded had been an excursion ship during peace time. We embarked and stayed there some time before sailing. We saw lots of equipment being loaded onto other boats bound for France. There were 14 of us in our cabin. Our cots were riveted to the floor. During the night we departed, most of the girls in my cabin were sick, but I was fortunate in not being sick any time. We stopped in the middle of the Channel and waited for the tide to go out.

We arrived off the coast of France the next day at 3 p.m. It had rained during the night and the gangplank was slippery. We heard boats being lowered all night as the men left. We had not slept much as they said we would leave early but when our turn came it was already 10 a.m., and not 7 a.m. as they had told us. The English Medics were concerned for us about the slippery gangplank and suggested we go by the luggage chute which was made of nylon. So we turned our belts around so they could not catch and slid down into an LST. When we were all safely aboard, we set sail. We went a distance and then the anchor was dropped in order to wait for the tide to go out. We had no place to sit. Then the tide went out and they started up again and landed us on the beach. Here were our inevitable trucks awaiting us. After a very short trip, we were taken to a field where the 9th Field Hospital had been set up. The entire staff were out on the battlefields. Our men had a huge fire and prepared a wonderful supper for us. We had passed American Engineers working on the road and I believe they threw their hats up in the air, and let out a yell, ‘American Women’!

We were told never to leave the road as the fields were still mined. I had heard about the hedgerows in Normandy, France but never realized what they were like. They were so high a tank could hide behind them. Everywhere there were signs, ‘Mines Cleared to Hedges’. Montebourg was only two miles away so one day we walked over there. It was famous in WW 1 (?) and it had changed hands seven times before remaining in the Allies’ hands. The women were washing clothes on flat stones in the river.

Many of our Nurses were sent out on detached service, and the rest of us went by truck to Cherbourg. We expected to set up a Hospital but we were doomed not to do so. We were quartered in large tents set up in a field. We had cots to sleep on with our bedrolls hanging over the end at the top so we might get things that we needed out of them. We ate from our mess kits. For water we had large Lister bags made of canvas hanging between poles. Hot water was heated in large cans over huge fires. We washed our own mess kits with water provided for that purpose only.

Here, too, we went exploring the country. We were accompanied by our Protestant Chaplain and sometimes the Catholic Chaplain came along too. One day we explored some German pillboxes and found chickens. Another day we went to visit a Château. It was one the Germans had lived it. The windows had all been shot, while looking around, French women came out shouting, “First the Boche! Now the Americans” our own camp! On our way we met a couple of pious people, who were trying to find their way among the debris and the mines. Two of our MPs came along on motorbikes and gave them a ride. They drove away crossing themselves. We then left to go back to base.

We were here only two weeks when some of us were sent out on detached service. I, with four other Nurses, were sent on temporary duty to the 5th General Hospital in Carentan, France. This was a tent Hospital. We thoroughly enjoyed ourselves while there. We saw where a shell had embedded itself in the Chief Nurse’s stand. If she had been there she would probably have been killed. We saw Engineers working hard to raise ships out of the Channel. There was a bridge that the Germans were crossing when it was blown up. Many buildings had been bombed. There was a great deal of fresh fruit that we had hoped to enjoy during our stay, but then we received orders to go back to our own unit.

Back with the 203d General Hospital, everyone was hustling around getting bedrolls and packs ready so we could leave in the morning. We knew before we left where we were going as a newspaper correspondent had told us. The 5th General Nurses knew it too, and they resented it as they had been promised the Hospital where we were going! We left Cherbourg in a downpour of rain, it was August 28, 1944. We were taken to the train in trucks. They did not have enough cars so some of us were bedded down in the baggage cars. All along the way we saw a great deal of German sabotage. Railroad locomotives had been turned over and tracks torn up. We were the first to travel over this route after our men had repaired the tracks. There was only a single track most of the way. At times we would have to draw up on another track to let a train come through. When we did this, the French would come with either fruit or vegetables to exchange for our K-Rations. One night a train of German PWs stayed all night on the other track. They sang nearly all evening. Supposedly one tried escaping, but after a shot was fired into the air, he decided not to run for it.

After a pleasant trip, we arrived at Garches, six miles from Paris. Our Ambulances met us and took us to our Hospital. It had been built in 1939 but the French never had a chance to use it before WW2 broke out. We were taken to our quarters. We had beautiful quarters, such a relief after what we had had before. The French people who lived next door helped to carry our luggage in. One of our Red Cross workers played the piano and we all sang both French and American songs.

The next day we went to the Hospital and with the aid of the French we started getting the buildings ready for use. We started with Building “A” and after that was cleaned, we went on to “B” and then to “C”. We also had the old Hospital building to use for the ambulatory patients. There were 79 steps to climb up to our quarters on the top of the hill, and such rickety steps, but later our men replaced them with cement steps.

It was supposed to be very secretive where we were, but I received a letter, enclosing some clippings and telling everything. I put the clippings on the bulletin board, with my name on it. But the next morning they were gone. A letter from my cousin who was married to a Frenchman said her husband knew just where we were as he had camped on that hill as a Boy Scout.

Members of the 203d Gen Hosp pictured in front of the Eiffel Tower, during the unit’s time in Paris, France.

One night we had an air raid which we went through without problems. We were looking out on Paris, and were supposed to put our lights out, but not so the French people. They had their lights on windows. We understood that the bombs had fallen somewhere in the neighborhood.

We had one day off a week and we made good use of it to see the surrounding country. One time I went to Versailles and saw the ‘Hall of Mirrors’. Here the Peace Treaty of WW1 (Armistice) was signed. The picture gallery had many famous paintings, among them one of Washington and LaFayette. On my first trip to Versailles (Palace) they did not have any pictures up. They had all been removed and hidden to save them from Herman Goering (German Field Marshal) who was moving all the valuables to Germany. But on my second trip back they were hanging them again.

To get to the Versailles Palace, I was given a ride in a jeep belonging to another unit. We were stopped by the MPs because we were going 40 mph in a 25 mph zone. The enlisted men told the MP (who was an Officer) that they would hate to be in my Hospital after the incident. I asked the Officer what would be done about the speeding charge. He said he didn’t know but had to turn it to the Provost Marshal. Later I was called into the Chief Nurse’s office to be told, that even if it was not our vehicle, I, as the senior Officer, was in charge, and to be blamed! I was told to be more careful in future!

On another trip we went to Paris on a tour arranged for us by the Red Cross. This was after the ‘Off Limits’ to Paris had been removed. We had often gone into Paris before this, but we then signed out for St. Cloud, which was not off limits. Our Chief Nurse used to say we would get caught and the MPs would stop us, but they never did. On this particular tour, we saw the ‘Obelisk’, one of three in Europe. The others are in Rome and London. Concorde Tower was where the guillotine was located and where Marie-Antoinette was a prisoner and was later beheaded.

Another time we went to the ‘Arc de Triomphe’. At the time, there was only one soldier buried there. A blue light burned there continually, and as military personnel passed, they would salute. Later others were buried there too, one was a woman. On one side of this arch were the names of Napoléon’s Generals and on the other, the names of his many Battles. We saw the ‘Eiffel Tower’ which was being used by our Navy for radio communication purposes. The Tower contained over 900 pounds of steel. At that time we thought that was a great deal of steel, but not anymore. It was 900 feet tall and named for the builder. It was rumored that when Hitler took Paris he climbed to the top of it and looked over the surrounding country, gloating over his recent achievement. We also went to see Napoléon’s Tomb; he is buried in the ‘Dôme des Invalides’, near the Madeleine Church. They claim that Hitler visited the Tomb and said, “Hah, I’ve done something you couldn’t do”! Then, they say, Napoléon answered and asked “What was that”? Hitler replied, “I am Master of Europe”. Then came a rattling noise and Hitler said, “What was that noise”? Napoleon said, “Oh, I am making room for YOU”.

On another occasion we went to Fontainebleau, Napoléon’s home. Here he crowned himself and denounced the throne. The Fontainebleau name is attributed to a nobleman, who was lost in the woods while taking a walk with his dog, ‘Bleau’. He named the Palace after his dog and a fountain. The Palace itself is surrounded by 45,000 acres of land. There is a cave where the women would bathe in the evenings. At one time there was a great deal of wildlife, and the wolves were so thick they would attack the people. But they are all gone now. After World War 1, the Palace was occupied by the American School of Music, and Rockefeller donated over $50,000 to fix it up. They were hoping he would be generous again after World War 2. For myself, I think the money could be put to better use.

After entering through the gates of Fontainebleau, we saw three buildings. We were not able to find out what they had been used for. Statues of horses were all over the front lawn. The main entrance to the Palace was in the back. Francis the First and Louis XV had resided here. We visited the Throne Room with not much furniture. Joséphine’s rooms were roped off, but we saw them. We saw Joséphine’s bathtub which looked like one of our foot tubs. They claimed she could not take a bath without permission from the priest, but our Catholic Chaplain pooh-poohed the idea. Joséphine’s rug had swans in it which was supposed to be for fidelity. But she didn’t know what that meant. The floors and chandeliers looked very old. In one room we saw a desk that had a mark on it which was supposed to have been done by Napoléon in a fit of anger when he denounced the throne. Most of the pictures and furniture had been hidden from the Germans during occupation.

On our way back to Headquarters, we passed through Melun, the home town of Barbizon who painted such famous pictures as ‘The Gleaners’. This picture was sold to an American for $500.00 and later sold back to France for $5,000.00; Barbizon’s house had quaint furnishings.

We ate lunch at a French restaurant. We were served a cold meat dish, onion salad and a delicious bread. I thought that was not much to eat for the price we paid, but they served a dessert too.

We also passed through Ste. Germaine, a famous battlefield of World War 1. It was a railroad town and had also been bombed frequently during the World War, although the Germans were never able to completely destroy the railroads.

This was the last of my tours as I was to be sent home shortly afterwards. Several of the Doctors had asked for me to be in charge of their wards but the Chief Nurse said she did not want to show favoritism so their wishes were not granted.

I asked for a transfer and was assigned to the 1st General Hospital. From there, I was sent home. It was a beautiful day when we left at around 6 o’clock in the evening. The flight and the scenery about were gorgeous. I was sitting on the clouds, and they seemed to take shapes, some times.

We stopped first in the Azores. It was windy and as I put my hand outside the plane, my cap blew off. Down the runway it went with an enlisted man chasing it. One of the Azores Red Cross workers sewed a missing button on my sleeve. Our next stop was at Newfoundland at 1 p.m. where we were served fresh eggs, bacon and fresh milk. We were never able to get these delicacies overseas!

In New York, we were supposed to have landed at Mitchell Field, but because of bad weather, we landed instead at LaGuardia. We encountered some red tape and had to declare what we had brought with us. We went by car to Long Island. While we were stationed at Long Island, I visited two cousins. From there on we were sent to Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey and from there to various Hospitals. I went to Chickashee, Oklahoma, had numerous furloughs and then traveled on to Santa Barbara, California for rehabilitation. We had a grand time in Santa Barbara before we were transferred to Camp Beale, Marysville, California.

After a last physical examination, which proved there was nothing wrong with me, I was given the choice of staying in the Army or being honorably discharged. I chose the Discharge for, after being overseas, I thought it might be too dull to stay in, but I am very happy to have had the chance to serve my Country.

After my discharge I went back into the Indian Service for a while. From there I joined Barnes Arnold Army Hospital for two years. It was here that I met my future husband.

So – the fortune teller at the 1934 World’s Fair was half right. I did take a trip across the sea, but I am still waiting for the ‘lots of money’.

Elinor Walker BIRD died in Sioux Falls, South Dakota in October 1982. She was 82 years old. A Service of Committal was held for her at the National Cemetery, in Portland, Oregon.

The authors would like to thank Dan Leary (ASN: 39232383), (X-Ray Technician) who initially collected the original text from which this Article is derived, in his collection of

203d General Hospital Testimonies entitled “203rd GH: An Anthology of Members.” We would also like to thank him and his family for their kind donation of some of

the images which appear in this Testimony.

The authors would also like to recommend the excellent website dedicated to the 203d GEN HOSP, which includes a detailed history and a plethora of images relating to the unit. It can be found here.