Veteran’s Testimony – Frances Cardozo Jones 50th General Hospital

Studio portrait of First Lieutenant Frances Cardozo Jones, R-676, 50th General Hospital.

Introduction & Early Life:

The following Testimony has been compiled from the original memoirs of Frances Cardozo Jones, which were edited and forwarded via her daughter, Jana Steed. It forms part of a section of her complete life history entitled “In Her Own Words: The Life History of Frances C. Jones”.

Frances C. Jones was born on 6 November 1917 and grew up in Montana. She attended the University of Montana majoring in Dietetics, after which she completed an internship at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, New Jersey. After successfully completing her internship, Frances transferred to Pontiac General Hospital (Pontiac, Michigan) and finally to St. John’s Hospital in Helena, Montana before the outbreak of World War II.

Induction & Training:

While I was working at St. John’s Hospital in Helena, Montana, Pearl Harbor rocked the world on 7 December 1941. In the summer of 1942 I went on vacation to Seattle, Washington and visited a high school friend, Margaret Morrison who was a Nurse at Harborview Hospital (located in King County, Washington, affiliated with the University of Washington –ed). Harborview was setting up an overseas unit and was short a dietitian so I decided to be adventurous. Many times I have heard my mother say how relieved she was that “All my boys turned out to be girls so none of them have to go to war.” When I told her I was going, she said, “I don’t want you to go, but I’d go myself if I were your age.” She would have too, because she was a graduate dietitian. My parents were living in Great Falls, Montana then and I had two weeks before I had to meet my unit at Camp Carson, Colorado Springs, Colorado (68,355-acre Division Camp, with facilities for 44,240 Enlisted Men, 1,818 Officers and 2,707 Nurses –ed) on 13 September 1942.

On the train to Colorado Springs, I hoped to meet other 50th Gen Hosp personnel and was disappointed that I did not find any. However, there was no disappointment in my reception at the station. Due to an error, the base expected the entire unit on that train so I stepped out to rousing band music from the Camp Carson Band, and all the brass and a convoy from the Motor Pool. I was embarrassed and the Commanding Officer (Colonel Rollo P. Bourbon –ed) was annoyed, but I was taken in his official Jeep out to the camp. Upon arrival, I was showed to a huge empty barracks and told to help myself to the room of my choice.

The next day the rest of the personnel arrived and from then on my Second Lieutenant bars were just a pair in the crowd. There were 2 (two) Dietitians, 2 (two) Physical Therapists, about 100 Nurses and I don’t know how many Medical Officers and Enlisted Men. We joined the staff of the existing Hospital personnel and went right to work. Our on-duty uniforms were tan and white seersucker with matching caps. Our off-duty uniforms were navy blue shirt, jacket, sweater, cap, overcoat and cape. We were issued black shoes and high four-buckle overshoes. At a later date at Carson, all this changed and we were issued olive drab skirts, shirts, coats and capes and white on-duty uniforms and caps. We were issued male fatigue uniforms and combat boots, as well as duffle bags and Musette Bags and gas masks.

This was basic training so we were required to do most of the things the male personnel did. We learned to march in formation and set up a field hospital under fighting conditions. The only obstacle course we were expected to maneuver was crawling on our bellies across a field where live ammunition was being shot. We were expected to go through gas mask training by running around a building four times until we were out of breath, then put on our gas masks and walk slowly through the building filled with poison gas. We went on 30-mile hikes but were not required to carry a full pack as the men did. We were expected to keep up with the men on a 20-mile hike up Pike’s Peak but our packs and tents were carried on trucks. The men carried their own and were resentful that they had to pitch the tents for us and dig us a slit trench for a latrine. This was winter in Colorado and our canteens froze at night if we didn’t sleep with them.

The happy couple! Frances and Earl Jones pictured shortly after their wedding ceremony on 2 October 1943.

Recreation included trips to Denver, dining and shows in Colorado Springs, trips to Pike’s Peak, Garden of the Gods, riding horseback and skating at the famous Broadmoor Ice Rink, the only one of its kind at that time. The camp had a good Officers’ Club with dancing and dining and a theater. Several Nurses and I went to the Broadmoor Hotel ice rink. As was my custom, I climbed off the ice when a speed skating number was called. A very tall First Lieutenant came and sat by me; he was from Arizona and hadn’t done much skating. We got talking and he invited me to dinner at Colorado Springs the next night and asked how I was getting back to camp after skating. I told him I was with four other girls and we were taking a bus to Colorado Springs and another out to Carson. He invited us all to go back with him and his officer friends in their already crowded Jeep. We saw each other every day or evening or both for the next three weeks.

Meeting Earl had come about on the day after I had decided that I needed a church involvement. I always went to church on the base but could never feel that it could be right. I had walked up into the nearby woods to try to find an answer. I prayed, but I knew my prayers weren’t very good because I had been brought up in a home that laughed at religion. But I asked and I received an answer. This Mormon man was just right for me and me for him. We were married six weeks after we met. I knew this was too quick and we both had apprehensions, but we knew it was right. My outfit was ready to leave for overseas in October and he was a Commanding Officer in the Infantry and our future was uncertain. We were married on the post on 2 October 1943. A man and his wife from Earl’s unit acted as witnesses for our marriage, and the Army Chaplain, Reverend England, married us. Unfortunately, none of our relatives were able to attend the ceremony. I had asked the head cook to bake me a wedding cake and he was disappointed because he had already planned to bake it for a surprise. We took it to the room of the witnesses and that was the extent of our celebration. Earl had rented us a room in Colorado Springs and we both had to keep our rooms in the barracks; we also had to inform family and friends not to send wedding gifts. The 50th General was delayed in leaving so we were together longer than we thought we would be. We had the chance to visit Earl’s parents in Arizona for a few days, and on 23 December 1943 I said goodbye to my husband over the tailgate of an army truck.

Frances and Earl Jones pictured during leave in the United States.

Preparation for Overseas Movement:

My unit travelled by train to Camp Myles Standish, Boston, Massachusetts (Staging Camp for the Boston Port of Embarkation –ed) where we spent Christmas sitting on our footlockers with about 200 other Nurses, Dietitians and Physical Therapists. This was a bleak Christmas; no gifts, no lights, and the weather was bitter cold. I learned to knit using a tent stake for a needle and rope for yarn until the Chief Nurse, Qoralee I. Steele, got permission to go into the nearby town and buy us the proper equipment.

We sailed from the Boston Port of Embarkation on 29 December 1943 and were on the high seas on New Year’s Day, 1944. We slept in four bunks high, ate Navy rations. There was no place to even walk around. We were not allowed to go on deck because no one must know there were several hundred women aboard. The ship was in an immense convoy of ships of all kinds as far as the eye could see; troop ships, tankers aircraft carriers, battleships and many that I could not identify. We zig-zagged in this great armada through the rough weather of the North Atlantic. Submarines were reported but no damage was done.

United Kingdom:

We landed in Liverpool, England on 8 January 1944 and were taken to a Oulton Park, Cheshire the same day. This camp, built for the British Army, in total blackout and with incessant cold rain was, at best, uncomfortable. Most of us had acquired colds, coughs and diarrhea, the latter of which I had badly. I spent my nights trying to find the ‘ablutions’, the bathroom, which was about a block from our quarters. There were raised paths to follow but only mud and water if you got off the path. We were allowed no flashlight or light of any kind because all of England was in total blackout. I would have taken a blanket and hunkered down on the floor of the latrine but there was half an inch of water all over the floor. GIs who came into our room occasionally to get warm or to keep our fire going in our potbellied stove patrolled our barrack continuously.

Photograph showing the main gatehouse at Oulton Park, Cheshire, the 50th General Hospital’s first home in the United Kingdom.

Finally we went by train to Glasgow, Scotland, arriving on 16 January 1944. One impression I had was that of chimneys in the towns we went through. Each building had many, all puffing smoke. During the day, I was impressed by the many black-faced sheep in green fields all separated by stone fences that ran up to and over the hills and everywhere. The Scottish people were very friendly but I never got used to the children begging on the streets; not because they were poor or hungry, but because it was the accepted thing to go up to a “Yank” and say, “gum, chum.”

Our assignment was to Cowglen Hospital, at Boydstone, on the outskirts of Glasgow. We were a holding hospital, which meant the patients stayed with us until they could either be returned home, or back to duty. The invasion of Normandy had not yet taken place, so we had no American battle casualties although we had two large wards of venereal disease patients and a women’s ward besides the regular ones. One of the patients in the women’s ward was an Army Nurse who didn’t know she was pregnant when she sailed for Europe. She was not married, and the man involved was a G.I. who was already ‘somewhere in Europe’. Since she was having problems with her pregnancy, she couldn’t sail so she had to be kept in the hospital until after the baby was born. The night the baby arrived the hall was full of G.I.s walking the floor for her. Nurses had made diapers and clothes from their own nighties and apparel. The cook made a birthday cake and the carpenters made a basket with a cover to carry aboard ship as the weather was very bad. The father was found and a wedding performed very shortly before the baby was born. The little boy caused many problems because there was a rule that NO male patients were allowed on the women’s ward and also that NO civilian patients were allowed in the Hospital whatsoever, and he was both male and civilian!

Our quarters had about 200 Nurses in long rows down the sides of two long rooms, with clothing racks down the center separating the two rows. After about every two racks was a table with a gallon bottle of cough syrup. All of us had bad coughs.

I intended to see as much as I could of Scotland, and on every day off I took a bus trip somewhere or rode somewhere on the bicycle I bought. One of the places I rode to was the Paisley factory in Paisley. On display were the beautiful shawls and robes made for queens and royalty. I’m afraid I caused a bit of commotion from the people seeing an American woman in uniform riding along busy roads and strange city streets. I visited Loch Lomond, Loch Katrine, Loch Ness, Balloch, and Rouken Glen and all the beautiful areas of the Trossachs. I saw Ellen’s Isle of Scot’s Lady of the Lake, and visited Ayrshire and Robert Burn’s home. A special trip was to Kintore, a village in the Highlands that had once been the home of a very good friend of mine, Mary Christie Ray, from Helena, Montana, and her cousins from Columbus. Mary and her cousins had left Kintore when they were about sixteen to work for the Canadian Government, and then they were on their own. I had contacted Mary’s aunt by letter and received an invitation to visit. When I arrived in Kintore by bus, I went to the Post Office to find where Mary’s old aunt lived. The postmistress said she had been the one to answer Mrs. Christie’s letters because the old lady couldn’t write. She closed up the Post Office and took me to the little thatched cottage, where a sweet little old lady welcomed me and fed me, cooking at a fireplace, kneeling, as there was no stove. She explained the language and customs of the highlands, I could understand the Scottish words only slightly. “Yer a lang way f’hame”, they would tell me. She took me to her daughter’s home where there was a celebration in my honor and the whole town turned out, not because I was Mary Christie’s friend but because I was Davy Watt’s friend. Davy was the cousin from Columbus who was a ne’er-do-well and a drunk. Mary was wonderful!

Aerial view of Cowglen Hospital (located on the outskirts of Glasgow) where the 50th General Hospital was set up.

While I was in Glasgow, I visited the University of Glasgow in hopes of seeing the dietetics department, or at least home economics. The head of the Dietetics Department, Shona Bell, was called to escort me and she became my very good friend. Shona was about my age, married to a doctor in the British Army, and had much of the same interests. She took me to visit her parents in Alloway, the home of Robert Burns. She visited me at the camp and was amazed at the way we lived. I stood watch with her, all night, as all British women were required to do, to watch for incendiary bombs. Her watch was the roof of the home economics building at the University of Glasgow. After the war, her children came along about the same time as mine, and they corresponded with one another as pen pals. I kept in touch with her for many years until she sadly passed away.

We were relieved of our duties at Glasgow on 3 July 1944. Since our orders for France had not materialized, we were temporarily assigned to Crookston Camp near Glasgow, called “Gonorrhea Gulch” by the Hospital personnel because of the large number of such patients. It was hot, dirty and uncomfortable. Finally, we received our orders. The unit’s staff went by blacked-out night train to Plymouth, a city almost completely flattened. We walked up the gangplank with heavy packs, bedrolls, duffle bags and all that we owned. It was not quite so bad for me because I was quite large and strong, but some of the tiny girls had a hard time. The plank was narrow and black dirty water was below it. We set sail aboard a British Hospital Ship, accompanied by the 298th General Hospital, and zig-zagged so much that it took us a day and a night to cross the English Channel, finally reaching Utah Beach on 16 July 1944.

France:

We debarked at Utah Beach. We were lowered in a boat but we had to wade quite a long way with full packs, and walk up the beach on a path. We were told not to step off the path because the rest of the beach had not been cleared of mines. All along the beach were large concrete ‘pill boxes,’ rolls of barbed wire and debris. In the water were many sunken ships. We were led to a field and told to set up our pup tents for the night. As soon as this was accomplished, trucks arrived to take us to our next destination under cover of darkness. In the trucks we traveled toward the sound of the fighting until approximately 2300. All of us desperately needed a bathroom but as we were in a men’s world, there were none. We would pass convoys of men stopped by the side of the roads but we were not allowed out. Finally with firing all around, we reached our destination, a hospital that had been taken over by Germans and evacuated by them only hours before we arrived (Cherbourg, in the Cotentin Peninsula –ed). We were told the beds were too filthy to use; we were to shake our small can of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane; insecticide powder issued by the US Army –ed) on the floor and put our blankets down on it. We were not to leave the building to go to the toilet or for any other reason. The more senior Nurses were allowed a flashlight fitted with a small, red-colored plastic disk, and they found a bathroom for 100 of us to use. We found it to be one toilet, full and stinking and a ‘bomb site’ toilet, not much better. Many of us sneaked out anyway. The next day we were allowed out of the building two at a time to fill our canteens. “C” Rations were brought in and the next night we climbed into the trucks again.

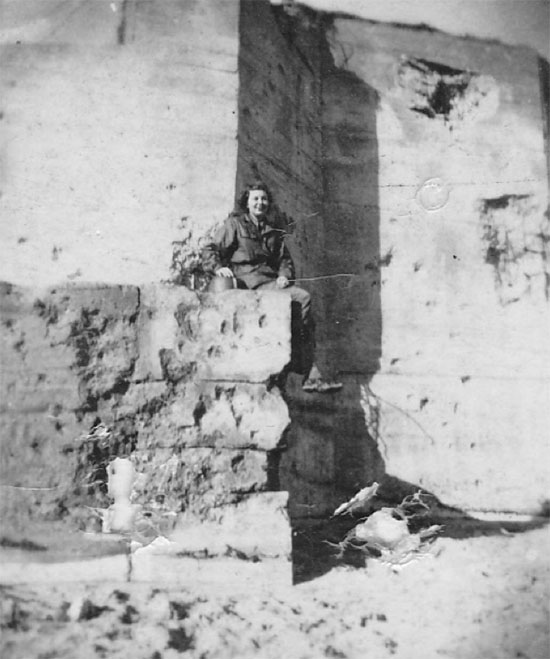

Lieutenant Frances C. Jones pictured sitting on a partially-destroyed concrete bunker on Utah Beach, July 1944.

The trip that night was towards the noise and flare of the combat. The long convoy was allowed no light and was guided only by the light of a red tail light on the back of the truck ahead. One town we went through had streets so narrow that we almost touched the sides of the buildings, which were being so shaken by shells that glass rained down from the windows. Wires were down across the street. We had to reach up and pass the wire from person to person over our heads, or be decapitated; fortunately, none of the wires were hot. We all came through safely except for the last two trucks, one of which missed a turn and went off the road and the next one followed its red taillamp. The girls in those trucks had to stay there until daylight, but thankfully no-one was hurt. Our goal was an open field where our Enlisted personnel had preceded us and pitched tents.

Our position was near the town of Carentan. Our equipment did not arrive for about a month and during this time we were restricted to camp as we were actually behind the German lines and the war was not going well. Unknown to us, our position was cut off from the US Army and we were in real danger. We had a good rest as we had nothing much to do. We lay on a hillside and watched the planes over the Battle of Saint-Lô. The ground all around us was strewn with strips of aluminium foil which had been dropped from planes to confuse the radar stations in the area. There was a US antiaircraft artillery battery close by and they had orders not to shoot at planes flying over us because we would get the flak. The only time we were ordered to our foxholes was when there was a dogfight in the sky immediately above us and flak was falling. One Nurse, Rosie M. McDonald, had a visit from an old friend who was an Officer stationed nearby. He brought his friends along who were thrilled to talk to American girls!

Cleanliness was a problem – we bathed and washed our hair and clothes in our helmets and our latrine was a slit trench with canvas screens around it. Later they put a ‘honey bucket’ sort of a potty with chemicals in a tent for us. After several weeks, our supplies finally arrived.

Our facility was set up among the hedgerows and before long we had hundreds of patients. The mess was a cook tent, a large dining tent and the office. As we were in total blackout, all of the tents had an entrance similar to an igloo, that the outside door could be closed before the inside door was opened. At times we would have truck load after truck load of vegetables like onions and potatoes. There is really not much you can do with all those onions but we had to use them or the Quartermaster wouldn’t give us any meat, so we buried them! The potatoes were too small to be peeled and about every fifth one was a rock, so we buried those as well. The carrots were too plentiful; after boiling, baking and preparing them every way, the boys got an idea. They scrubbed metal garbage cans until they were shiny clean. Then they scrubbed the carrots and put them in cold water in the barrels just outside the mess area. The ambulatory patients thought they were intended for a meal and stole them. Each one took several on their way out of the mess tent. Even the walk-in soldiers stole the fresh clean carrots as they left.

Unidentified Officer and Nurse pictured in Carentan, France.

Our quarters were tents housing six women each. We had canvas cots and as the rain almost never stopped, we slept with all our clothes under our mattresses and our shoes tied by the shoestrings to the cot. By the time the weather got really cold, we usually slept with wet hair, not very comfortable during the night. Our latrine was a “twenty holer”; ten back-to-back over a pit. After a while the pit filled up (lots of Kotex) then it had to be covered with gasoline and burned out. What a stench! We had a shower tent that wasn’t well staked down. In very cold weather the wind whipped under it on our wet bodies. In spite of the cold, we were surprisingly healthy and there was only one casualty. One Nurse who had pneumonia three times died of it. She was buried in a soldier’s cemetery. When we left there, it was bitter weather and the replacements for us arrived in dresses and nylons. Before we left, almost half of them were patients themselves!

Some of the Enlisted Men and I wanted to learn French. I had it in high school but remembered very little. We hired a young man to come three evenings a week and teach us French. He did a good job and had material for us to study. We had our lessons in the Mess Office. One evening I had arrived for a lesson just after dark. The electric system had failed and as I went into the almost dark tent, I recognized our Sergeants pumping up a lantern. I could see that there was someone in my office who didn’t belong there, standing outside the ring of light. I went right up to him to see who it was. It was my beloved Earl. My steel helmet fell off my head and bounced and clattered over the cement floor. I had not seen him for eleven months! I had not even known that he had left the States; I was a mess. In the constant rain, my hair seldom dried out and on top of that I wore a seven pound steel helmet and men’s fatigues. He didn’t care and neither did I.

Earl had arrived at Omaha Beach that day and after finding his camp, he asked a military policeman if he knew where the 50th General Hospital was. The MP flagged down an ambulance, and Earl, on a 5 minute alert, came the 20 miles to see me. My Commanding Officer let us take an ambulance and driver to take him back. On the way to Omaha Beach, the driver got lost in the rain and muck and terrible roads and Earl said, “Let me drive.” He drove right there. His CO called him in about it and my sweet husband said, “Sir, what would you have done if your wife was over here?” So the Officer tore up the paper and nothing more was said, except the next day there were several Officers who stopped an ambulance and came to visit the 50th General to enjoy a good mess, and company of American women!

We had no privacy of course. There was no place for Earl and me to sit and talk out of the rain until we found a bombed out farm house that was dry in one corner and we could sit on a pile of rubble out of the rain. It overlooked the beach where we could see all the sunken ships, the concrete pillboxes, the tangled wire, and distressful signs of death.

A near disastrous incident, but amusing now, was my trip to Carentan, the town nearest our camp, to get a permanent wave. With Earl so close, I wanted to look my best. After weeks of wearing a heavy steel helmet on wet hair, I decided to improve my looks. We women were forbidden to leave camp unless we were accompanied by an Officer but about noon, I slipped off by myself into town. I found a beauty parlor, which was quite primitive, still using the electric machines that let down from the ceiling to fasten hot rollers into the hair. I was horrified when the operator sat me next to a French girl and put up the right side of my hair and the left side of the French girl’s hair. It was a very slow process at best, not hurried by the fact that halfway through the electricity went dead. I couldn’t leave nor explain my situation because my high school French was inadequate. By the time I was finished, it was after dark, in total blackout. I had several miles to walk in the mud and rain. In the dark narrow unfamiliar streets, I was totally lost and frightened and could see to walk only in the center of the cobblestone street. After a while I heard a Jeep coming. I could not avoid being seen but made up my mind that if they were Americans, I would ask for a ride. It was American soldiers from another unit delighted to help an American girl, especially one who was where she shouldn’t be. However, when we got to the place we both thought should be right, there was no big sign. We knew it had to be there. It was the right place, though, as we could see the tents and I was grateful to be ‘home’. I slipped through the hedgerows and open spaces to my tent to find out that the Hospital was moving the next morning. In the confusion of packing and moving over 600 people and equipment for a huge General Hospital, no-one had missed me or was too busy to do anything about it. I could have been court-martialed on four counts.

The day after, I received word that the 71st Infantry Division had been moved to Le Mans. Earl was with the 71st. That day we were moved past Le Mans. On this trip we had to go from one railway station to another on opposite sides of Paris. Our transportation was unreliable, and we had to walk across Paris with our packs and wearing our helmets. At one rest stop I was holding my helmet to relieve my neck and head and a French lady came up and put a One Franc note in it!

Exterior view of wards of the 50th General Hospital, Commercy, France

Our new location was an abandoned French men’s hospital near the town of Commercy. It was not yet equipped to American standards, mainly no inside plumbing. None of the homes in Commercy had baths and the situation was taken care of by two public showers where men and women showered at the same time in a large room. The Americans took over one shower for our use until ours were completed. It was a large room with drains in the cement floor and pipes overhead that had holes at various intervals. You pulled a string to open the hole and the water ran, not showered. The room was equipped with a boiler for heating the water and the Frenchman who took care of the boiler stayed there no matter who was showering. My hair was gray and thick with the dust from the long truck ride so I ignored the Frenchman and when it was time for the Nurses to take their turn, I was there. I had my hair really well lathered with black rivulets of dirty, soapy water running down my body when the water stopped. That was it, no more water until the next day and no arguing with the Frenchman in my bare condition! He left before I could get my clothes on. The only other water available was drinking water so I wrapped a towel around my thickening hair and waited until 1430 the next day when our turn came again. The other girls were in the same spot.

Our large 100-bed room had only one pot-bellied stove for heating. We had to haul our own coal (when there was coal to haul and if anyone would haul it) so we seldom used it. Only a very few could enjoy it at a time. It was November and long icicles hung from the roof. We were under total blackout at all times.

On the day before Thanksgiving we received word of the arrival of 200 patients to the facility. This was the worst part of the war and we wanted to give those men a hearty welcome with a big Thanksgiving dinner, so our kitchen personnel stayed up all night getting turkeys, thawing them and preparing a beautiful dinner.

The patients arrived; 200 Russian soldiers dying of malnutrition, overwork and tuberculosis. They were covered with dirt and lice and the shock of a shower actually was too much for many and they never lived long enough to be put to bed. Not one bite of our beautiful dinner could they eat. Of course Thanksgiving had no meaning to them. Through an interpreter we found that they wanted clabber with sugar on it. The survivors gradually gained strength but when they received their food, if they could not eat it, they hid it; pancakes in their pillowcases and mashed potatoes under the covers. They never trusted us and as soon as they were able, they sent spies to other wards to be sure other patients weren’t getting anything they weren’t given and to pick up information. As they became more mobile, they stole anything they could get their hands on; sheets, pillowcases, clothing etc. and took it into Commercy to sell.

As the weather became very cold the icicles hung three or four feet from the roofs of all the buildings and the snow was deep. My office was in a very dilapidated building with thin cracked wooden walls. The foot that I had frozen when I was in college was so swollen I couldn’t get a shoe on so I wore 4-buckle overshoes with many pairs of socks and no shoes. Part of my duty was to supervise the ambulatory patients’ mess and to do this I had to stand outside in the snow. The doctor issued orders that either I would have to be hospitalized myself or have better working conditions, so the Engineers ‘procured’ (probably stole) wide heavy sheets of thick rubber and wrapped my office in it.

On the patients’ roster one day I noticed the name Kathleen Rafferty. She was my college roommate! She had multiple sclerosis and was being sent home but for a while she kept herself busy helping us in the mess office. Kathleen passed away shortly after arriving home. One of our own Nurses, Helen Riggs, was sent home because of the same disease.

I was made First Lieutenant and Head Dietitian because I outranked the other Dietitian (Marian E. Moore –ed) by about two weeks. She was older than I and more experienced too and refused to speak to me unless she had to. She totally disapproved of my going among the wards and talking to the men on special diets to learn their likes and dislikes but I considered this important. She disapproved of my friendship with ‘my’ cooks and other kitchen Enlisted personnel but these men were fine young men and I liked them all. Finally she told me, “I can do you dirt and I intend to!” I always wondered what it was. And there were other things like my friendliness to a German prisoner who was assigned to help us stock shelves. He hated the war like we did and he wanted to do no wrong so that he could go home to his wife and children. I got well acquainted with him against all orders.

The prisoners’ enclosure was on our grounds. On Christmas Eve rumors came that there would be a short period of respite for all Hospital staff. All the female personnel, except a few Nurses, were confined to quarters and were allowed no light, not even a flashlight. What a Christmas! Every girl seemed to feel it was her duty to make a happy Christmas for the rest of us. The resulting spirit was beautiful and it was calm and happy and almost a Holy feeling of sharing stories. We sang, joked and shared food boxes and had one of the best Christmases of my life. The break never materialized…

Our Enlisted personnel were starved of female association and so they had a dance, inviting the local French girls from nearby villages. I helped them make pretty little sandwiches and cookies for refreshments. When the time came to eat, each girl brought out a large bag into which she scraped all the food she could to take home. These people were almost starving and had come to the dance for this purpose only. At the subsequent dances our boys made large hefty meat sandwiches and lots of them and that was fine with the girls.

French girls were hired to help serve and clean up after the ambulatory mess but they stole away every bit they could, sometimes dumping pounds of sugar over the fence into a waiting receptacle. At one time a young woman came to our mess office carrying an emaciated baby and begged for a can of milk. I was about to give it to her when the Mess Officer stopped me. He said that if I did, by the next morning we would have a line from here to the village.

The best part of this time was my visits from Earl. We could contact each other by phone although this was not very satisfactory as a message had to be relayed through four or five operators and the answers relayed back. They were glad to do it because it added a bit of romantic interest in their lives though we also gave them our liquor rations. Each Officer received one bottle each of scotch, bourbon and vodka. One day, Earl talked to someone for an hour, thinking it was me. The girl told him she was being transferred to the South Pacific and asked him to come to see her. The next day Earl hitchhiked to see me on an emergency leave. I was surprised to have an unscheduled visit from my husband but felt sorry for some girl somewhere who expected a visit that never came!

Earl was able to come to see me several times and I was the envy of all the Nurses. He would travel from Compiègne, and we would stay at a hotel in Commercy. We always needed our marriage license to get a room. The hotel was not too bad except there was only one toilet, flushed by carrying a pitcher of water from your room, down the hall to where the toilet was shared by all the guests. Earl always unloaded his gun when we were in the hotel room. Once it went off as he unloaded it pointed into the fireplace of course. It was amazing how fast French and American Officers arrived in our room. There were no restaurants or food available in the town so we packed food at the Hospital and ate in our room.

One day I received a letter from Earl saying that he was going to the front. As a Company Commander in the Infantry, his life was worth five minutes and he wanted me to try to get a leave to come to Compiègne. My Commanding Officer said that I could never get transportation there even if he granted me leave. I went to the Transportation Officer on the railway and asked what they could do for me. The GIs there said sure, they could, so I got my leave. I sat at the transportation office until a train came through at about 0300. It was a Hospital Train to Paris. The boys flagged it, opened a door and put me on in total blackout! I started walking on the darkened train. I met a man in pajamas who said he was an Officer and took me to the Nurse’s lounge where he checked my papers and I spent the night.

The next morning the annoyed Commanding Officer said I couldn’t get off the train in Paris because I was not wearing a dress cap. I had none so after he left I did too and found a Red Cross Office where I was able to obtain a replacement. I didn’t much like Paris; it was dirty and unfriendly. On the next day I found the Hospital Train bound for Compiègne, but it too traveled only after dark. At about 0230, it stopped and the CO announced that I had reached my destination. I detrained and it thundered off, leaving me standing in the center of a network of tracks with not the slightest idea what to do next. I started walking toward a red light. God must have been with me because the red light was at the post of a US sentry. The Corporal on duty was almost overcome at the sight of an American girl coming out of nowhere. I asked him how I could find a hotel room and he assured me that here were none but that he would be happy to take me to his quarters. Of course I quickly refused but the young man was so courteous, so pleased just to talk with an American girl and so insistent that it was really perfectly all right, that his roommate was on night duty too, and that he would give me the key to lock the room from the inside. I went and everything was just as he had said. The next morning I opened the door of my room hoping to find a bathroom and there stood a Major. I saluted and said, “Sir, did you know I was here?” It sounded awfully dumb but he was as surprised as I was and I had to explain myself. The Major was in command there and no human being could have been nicer. He took me to breakfast first and then he took me to the camp where Earl’s outfit was stationed. At the gate, a G.I. told us that they had all pulled out during the night, all except three men and he noticed one of those men coming toward the gate, a 6’4″ Captain. It was Earl! He had been held back because he is an instructor and they needed experienced men to teach the boys that they were pulling from non-combat ranks how to fight and kill and throw grenades since the casualty rate was so high and replacements were desperately needed. The Major found us a beautiful room in the home of the mayor of Compiègne who was very good to us but could not understand why we refused to drink with him and his family and was hurt by it.

My trip back was uneventful except for the fact that the transportation office in Paris had no indication of Commercy on its map or list and insisted I couldn’t go there. I had to go to Bar-le-Duc, which was about 20 miles from Commercy. There I found an American Offers’ Club. When I inquired about how I could get to Commercy, the said, “You’re in luck! There is an Officer from the 50th General Hospital here now!” It was not just one Officer, it was a whole Jeep-load of our highest brass, but they squeezed me in and took me home although I felt out of place and in the way.

Finale:

On V-E Day (Victory in Europe Day – ed), I was in Reims on R&R with Clara A. Guyer, a Physical Therapist and more importantly, dear friend. We had a lot in common; both being married and neither enjoyed the drinking parties most of the others did. Soon after, I was given the opportunity to fly home if I left the next day, but I delayed, hoping to contact Earl or see him again since it would be many months before he could go home, but I couldn’t. We were taken across France by empty Hospital Trains, which were merely boxcars with bunks and one flat car at the rear if you wanted to see where you were. This train had the lowest priority of any and we were shunted off onto sidetracks for hours. First we went to Paris and had to cross the city. Since we had no transportation we hiked with our luggage and helmets. We were in Marseille for a week or so and then sailed out through the Mediterranean and through the Strait of Gibraltar. We could see France on one side of the ship and Africa on the other.

Arrival in New York was a thrill to see the Statue of Liberty and American bill boards. The Red Cross gave us each a carton of real milk as we debarked. I went home to Montana to be with my parents until Earl came. I went to visit my Grandmother Cardozo in Los Angeles and my sister, Jeannette, near San Francisco and then took courses at the University of Montana at Missoula.

First Lieutenant Frances Cardozo Jones and her husband Earl pose for the camera in front of the 50th General Hospital’s sign in Carentan, France.

After the war, Frances and Earl Jones settled first in Scottsdale, then permanently in Phoenix, Arizona. They had three children, Judith Ann, Jana Carol and Kristie Lynn. Frances never practiced dietetics again but was a substitute elementary teacher for many years. She was a fabulous mother and friend. She passed away on July 15, 2005. She and Earl were very happily married.

The MRC Staff would like to express their most sincere thanks to Jana J. Steed, daughter of First Lieutenant Frances C. Jones (ASN:R-676) who served as a Hospital Dietitian with the 50th General Hospital during WWII. Jana was able to share with us detailed information and photographs of her Mother’s service and we are forever grateful of her precious assistance.