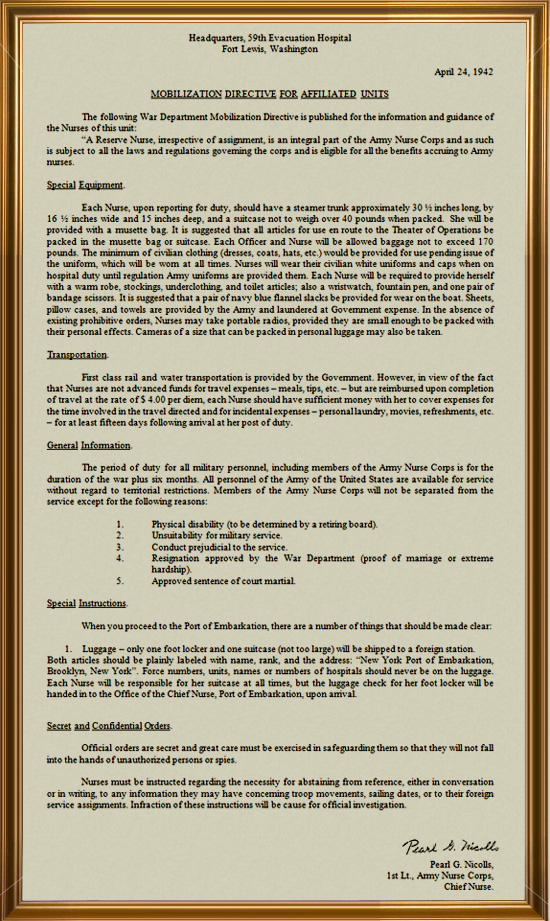

Veteran’s Testimony – Helen I. Hyatt DeKorp 59th Evacuation Hospital

Photo of First Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt, ANC, N-742643, General Duty Nurse, 59th Evacuation Hospital.

Introduction:

My name is Helen I. Hyatt. I was born October 19, 1915, near Masonville (46 miles north of Denver), Larimer County, Colorado, United States of America – one of seven children. My parents were Roy and Jessie (Roseberry) Hyatt. Both sets of my grandparents were pioneers traveling from Missouri to the west coast and then back to Colorado.

I attended a one-room schoolhouse in Masonville before moving in with an aunt to attend Loveland High School where I graduated in 1933 – during the worst of the Great Depression. I found work as a housemaid and, thankfully, finally was able to pursue nursing studies in 1936. I left for Nursing School at Springfield Baptist Hospital, Missouri, graduating from there in 1939. After graduation a friend and I moved to New York City to work in City Hospital on Welfare Island in Manhattan for about six months, then to a summer camp in the Berkshires for one summer. I had enough of the east and moved back to Springfield to work at my alma mater for a few months before being lured by a sister to San Francisco. I had such a yen to travel. I found work at Stanford University Hospital and was working there when I heard the news on 7 Dec 1941 of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. A friend from the hospital and I decided to join the Army Nurse Corps when a medical unit from Stanford General Hospital and University of California San Francisco Hospital was formed.

Helen I. Hyatt at Denver railway station in 1936, waiting to catch a train for Nursing School, Springfield Baptist Hospital, Missouri.

I effectively did on May 24, 1942. After enlisting in the Army of the United States and allotted ANC serial number N-742643, I became a Nurse, General Duty, MOS number 3449.

Assignment & Training, Fort Ord, Monterey, California:

Our hospital unit, designated the 59th Evacuation Hospital, was officially activated 6 April 1942. After reporting for duty in May of 1942, I was sent with a group of Nurses to Fort Ord, California, for training. The new site was located in a very nice area on the coast in the Monterey and Carmel area.

We were placed under the training supervision of one of the surgeons, Dr. Roy Cohen. He really put us through punishing paces and routines as we hiked in full army regalia, including unopened gas masks and carriers, canteens filled with water, and steel pots, for miles over the scrub oak carved hills, down the sand cliffs to the beach and back up at a good fast pace.

We were issued uniforms – consisting of a dark blue wool jacket and skirt dress uniform, and white blouse (my two dated from World War I with a collar up to the chin and buttons spaced about every inch down, my black oxfords were also from the same period).

We were there the whole summer, from May until August 1942, wondering if we’d ever get away when in late September, I think, we were placed on alert and readied to ship out – we presumed to the Pacific Theater of Operations. Instead we were loaded onto a Southern Pacific seven-car train and headed east.

Our Commanding Officer was a Colonel Oral B. Bolibaugh. He was a Regular Army man, member of the Medical Corps and a chest surgeon, I was told. Our first Chief Nurse was First Lieutenant Pearl G. Nicolls, ANC. She was young. For some reason she did not move with us from Fort Ord, and our new Chief Nurse, assigned from our unit, became Second Lieutenant Mary Diffley, ANC. She was gray-haired, flush -faced, and she stuck right in there as long as the unit stayed on active duty.

Our 7-Day Trip across the United States:

My memories of this are rather sparse. We were never, during the entire war, told our destination when we were moved or transferred from one location to the next.

We were traveling in a seven-car train. The Nurses were in the first 2 cars behind the engine. We must have had berths but I can’t recall them. We seemed to fly across the country at times and at others seemed to drag. We were told we crossed a portion of Texas and we spent what seemed an entire night being switched from one track to another, in, we were told by someone, Chicago, Illinois. We then went to Washington, DC, and further up to Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey, where we unloaded and ended up staying for a few weeks. This was a staging area for the New York Port of Embarkation. We had missed our boat to the landing in North Africa and operation “Torch” (November 8, 1942 –ed).

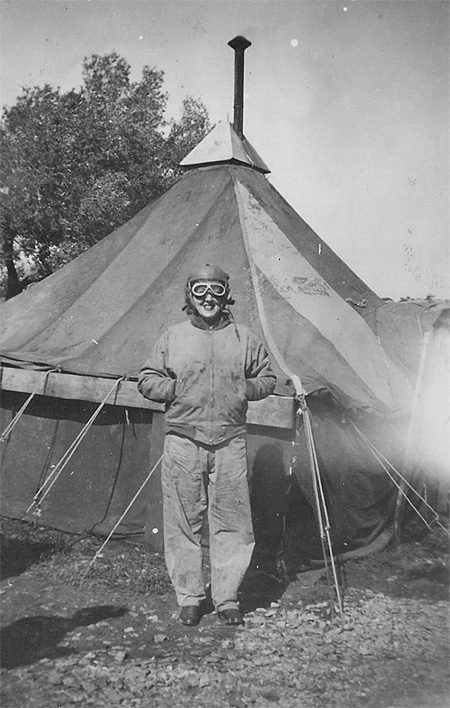

Second Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt, dressed up in a complete tanker’s outfit. Near Palermo, Sicily March 1944.

I remember civilians in the Midwest (was it Kansas? or Oklahoma?) coming to the train doors with candy bars and gum, as much as they could hold in both hands cupped, and shoving them at us as our train eased through their town. We thought it a nice gesture, and I still do. Like all of us in the States, they were so anxious to do something positive in our time of fear and helplessness after the Pearl Harbor attack (December 7, 1941 –ed).

Pre-Launch and Oversea Movement:

The dates of our pre-launch preparation for oversea movement at Camp Pickett, Blackstone, Virginia (where all equipment was packed and crated for a sea voyage –ed) and at Camp Kilmer in New Jersey, are long gone from my mind but each was of a few weeks duration – perhaps five to eight weeks at Camp Pickett, and four weeks at Camp Kilmer.

While personnel was being prepared for processing, we drew duty at both locations. Mine was in the station hospital at Pickett, and later in the dental offices at Kilmer. At Camp Kilmer we were still taken on long cross-country hikes and along the Raritan River. I remember Captain Bell, a very nice, tall, good-looking Medical Officer, leading at least some of these.

On December 11, 1942 we embarked from Staten Island, New York, having entrained from Camp Kilmer, Stelton, New Jersey. We were serenaded by a band playing inspiring martial music as we walked up the gangplank onto the USAT “Uruguay”, formerly a passenger cruise ship converted to a troop carrier (she made her maiden trip as a troopship in March 1942, was fitted with 4,800 bunks, and could carry over 8,000 troops, the “Uruguay” served in both the European, Mediterranean and Pacific Theaters during WW2 –ed).

Each stateroom had four to six berths bunk-style. We were quite excited at finally being on our way to somewhere overseas, though we knew not where…

We stayed the night in port but the next morning (December 12, 1942 –ed) pulled out into New York harbor and became one of probably a 20-ship convoy. Some vessels, were quite small, others as large as we (there were more troopships) and the group surrounded by, as I recall, at least one battleship, a cruiser and several destroyers. We ate in a very nice dining room and were served by white-coated waiters. The food was delicious and plentiful. In case of emergency, I was assigned to life boat # 10.

About the second or third day out we ran into a storm with very high seas, and considerable seasickness. I very nearly became a casualty when Lieutenant Mary Diffley (our supervisor) told me to go below to the dental clinic to assist with a patient. The dentist was caring for a poor GI whose face was greatly swollen from an infected tooth. The ship was rolling, the air in the room was hot and humid, and both the patient and doctor were turning green. The Dental Officer asked a corpsman to open a porthole to let in some air, the ship rolled to that side and we were deluged with a porthole full of sea water. With so much confusion we all rushed for the deck level where we could get outside and that took care of it.

A convoy of trucks pertaining to the 59th Evacuation Hospital makes its way through the streets of Palermo, Sicily.

Courtesy John Sateja

Leota Summer (my good friend) and I were assigned to a battle station in the very bowels of the ship and periodically we had drills to acquaint us with procedures, such as security measures and abandon ship drill. We couldn’t believe the number of GIs pressed in the room to which we were assigned, lying on bunks probably 8 or 10 high or sitting on them with almost no head space. We never learned how many men were living in that monstrous room, and as far as we knew we were the only Nurses assigned to that station. We were appalled at the number of men and the crowded living conditions and the absolute impossibility of any of us getting out of the place should we be attacked and sinking. The stair to upper decks (this was far below decks) was metal, narrow and winding. Thank God we never had the occasion to learn what would truly happen in an emergency.

We awakened one morning in mid ocean to find we were not moving. We were sitting alone except for two small destroyers circling us, around and around. I can say that this was quite frightening. Sometime during the day we began moving and when we got up the next morning there we were in our “safe” little nest in the midst of the convoy once more. As always, we were never told what had happened but I suppose it stands to reason that our ship suffered some sort of breakdown.

On Christmas Eve, December 24, 1942, we pulled into the harbor at Casablanca, French Morocco. It turned out our destination was North Africa!

Casablanca, French Morocco:

We were invited by the captain of the “Uruguay” to spend the night on board and have a real Christmas dinner with turkey and all the trimmings, as his guests on Christmas day. But that was not to be, for we were quickly hustled off the ship, ordered into formation on the dock, and marched somewhere into the French quarters in town and billeted in a former girls’ school. There’s not much that I remember about it except to say that only the bare metal beds were left in the sleeping cubicles and someone rustled up some GI white cotton mattress covers filled with straw to sleep on. There was no other furniture. Sometime after dark there was a bombing of the harbor by the Germans and so we had our first taste of the actual shooting war. We were ordered by our Chief Nurse, Mary Diffley, to lie on the floor under the beds and to wear our helmets. I started in that fashion but with the noise of the ack-ack I decided there was excitement out there and we didn’t seem to be too near the harbor, so I stood at the window. There was nothing much to see except the colorful tracer shells and a blob of flame somewhere on or near the docks where a bomb must have started a fire.

The next morning, Christmas Day, we had no GI rations and the kind lady who owned the residence had some of her female employees serve us what food she could scare up for breakfast and it was just awful. Black bread and black ersatz coffee. Nothing to improve the bitter coffee taste nor to spread on the bread but you may be sure, since we’d had no supper the night before, we were grateful for any food we could get.

Helen I. Hyatt with fellow Nurses in Paestum, Italy, in a 1/4-ton truck (aka Jeep). Picture probably taken in June-July 1944.

I guess we were billeted there for a few days and then taken in ambulances to Casablanca where our men had the necessary tentage set up and ready for the entire hospital. The Nurses were housed in pyramid tents furnished with four cots each, the male Officers too, I guess, but all the time we were there (and that was months), the Enlisted Men lived in pup tents. They were provided a large tent for a recreation room. We were quite some distance from the front so for a while were not busy, acting more as a station/holding hospital with patients from the units in and around Casablanca (QMC dock workers, etc.) and were not moved up until about a few weeks after the invasion of Sicily (July 9, 1943 –ed).

Random Memories:

Casablanca, French Morocco, was a beautiful European-type city in some areas. We found American servicemen to date and there was a good deal of social life going on. We wandered the streets of the main city, shopping, sightseeing, lunching at lovely restaurants and tearooms without fear. Their food was good, mainly fish and greens and fruits, a very welcome change from our rations (mostly “C”) served at the hospital.

Somewhere along the way we were issued olive drab (OD) service uniforms to replace the old dark blue garments. Our hospital working uniforms were seersucker, with narrow stripes of light brown and white. We had brown oxfords and brown utility bags and pocket books and brown gloves. OD wool suits (skirt and jacket) for formal wear including a shirt and necktie, and a one-piece summer dress of dark olive drab for dress up. All had to be worn with the official insignia. We had two types of hats, one called “overseas” and one with a front bill, looking smart. They were a dark OD wool adorned with the proper Officer insignia, including the seal of the US.

Our Hospital:

Large and long olive drab tents were set up for wards with canvas folding cots lined up side by side on each side of the tent. The first section at the front entrance was made into an office area with desk and work area. We had taken with us from California medical field chests approximately 28 inches x 16 ¼ inches x 14 ½ inches. Some of these were used for field administration while others contained a number of medical and surgical supplies. Our entire charting consisted of notebooks for doctor’s orders and bookkeeping ledgers for two lines of nurses’ notes on each patient daily.

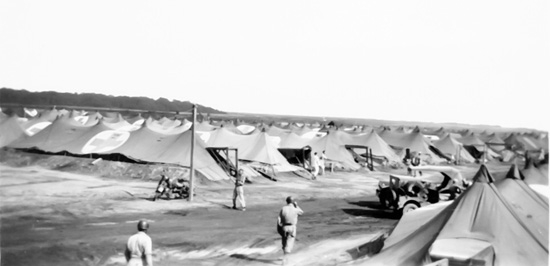

General view of the 59th Evacuation Hospital while stationed near Naples, Italy.

Courtesy John Sateja

Near the end of our stay there, two more tents were added end-to-end to the original one to serve as wards because we were to be inundated with patients coming in from the front at Kasserine Pass, Tunisia. After some heavy losses, hesitation, and renewed Allied efforts, Field Marshal E. Rommel was being beaten in the desert and there was all-out fighting to mop up the North African front. We did get a rather small surge of wounded, but after I was made charge Nurse of one of the last wards to be set up, we admitted few, and they stayed perhaps a week or 10 days before being shipped home on a boat or returned to their unit to duty or for transfer to another area.

We were in Casablanca so long it nearly became a home. We rented bikes downtown and brought them out to our area to ride on the country roads surrounding us. We were taken in a hospital vehicle to Rabat, a town some miles north, to a beautiful sandy beach where we swam and sunned.

Pauline Mahler, another 59er, and I were walking in Casablanca one day when we happened on to a US Navy Officer who was surrounded by a dozen or more ragged small Arab children. He asked us: “Can you get me out of this?” Seems he’d brought some candy off his boat and when he handed it to a couple of children he’d suddenly been mobbed by others coming from all directions. He did walk on with us and we learned he was Captain of a minelayer. His name was Pat McNulty, he and his crew were trained divers and when they weren’t laying mines they defused the enemy’s, inspected and repaired underwater installations. Our friendship was short-lived for we didn’t see him again nor ever heard from him. This was not unusual for the times we were in.

We were quartered in tents outside an Arab cemetery wall. Two or three times a day an Arab funeral would wind its way along the dry, dusty, dirt road at the base of the wall. There would be 8 or 10 to 20 or 30 native Arabs in their long robes and a few women bringing up the rear of the group sometimes crying, but more often chanting a prayer. Our supply tents were set up facing the same road and protecting their contents became quite a problem due to pilfering. The coffins at these funerals were always like a rough wooden tray either carried on the shoulders of four men or occasionally strapped to a two-wheel cart pulled by the emaciated donkeys that were the chief beasts of burden there.

Helen I. Hyatt with colleagues of the 59th Evacuation Hospital. Somewhere in Southern France, end of August, early September 1944.

One day we heard an aircraft coming in over the area. We were so far behind the lines by then we didn’t see too many American fighters and this was a P-38 with a very distinctive sound and appearance since it had a middle pod for the cockpit and two slender fuselage parts on either side connected at the rear by the tail. As we watched it seemed to be in trouble and sure enough we saw the pilot bail out and the plane hit the ground and explode as he gently parachuted to the ground in a dry valley east of us. An ambulance was sent out for him and he was brought to our hospital but not being injured was returned to his unit within a few days.

A Trip Across North Africa:

Sadly, I’ve not kept track of dates in our North African journeys. But eventually we did leave Casablanca on a train with “40 & 8” railcars, famous in WWI for transporting men and horses, around mid July 1943. They were actually cattle cars and the Enlisted personnel traveled in those with our equipment. These were cars with only wooden slats along the sides, horizontal, and spaces between. We Nurses were in two European style coach cars. We were uncomfortable in the heat but could not feel sorry for ourselves as we knew the EM were riding in such awful conditions.

The steam engine was coal fired and the Nurses’ cars were immediately behind it so we ate plenty of cinders. There was only drinking water on the train and periodically it would stop at the old-fashioned water towers to resupply the engine. Eventually we were allowed to stand under the tower to be hosed down, fully clothed. This was the only “bathing” we did in the seven-day, seven-night trip. The train seemed to drag along unnecessarily and stop frequently. We began to wonder if our supplies, also in the “40 & 8s”, might be disappearing gradually but we were supposedly in danger if we wandered ten feet from our cars.

The coach seats were two to a compartment and quite long, facing each other. They were long enough for one person to stretch out on one for sleeping. Four of us were assigned to each compartment which meant two on the seats, one on the floor space between, and one on the aisle outside the door. During our many and frequent stops, Arabs would board the train surreptitiously. One night, one of our Nurses awakened to find an Arab man sleeping almost beside her.

When nearing the end of our journey, we heard a commotion and yelling, looked out our window, and saw a sergeant, rifle in hand, standing beside the engine looking very angry as he called up to the engineer, “If you stop one more time I’m going to shoot you”. We had no doubt that he meant it. He was in charge of the train and was sick and tired of the crews stopping and starting anywhere, and often, allowing the natives to climb onto the cars and throw off anything they could get their hands on.

Illustration showing buildings and vehicles belonging to the 59th Evacuation Hospital in Epinal, France.

Courtesy John Sateja

That train took off and believe me, it got to Bizerte, Tunisia, our destination, in short order, where it arrived July 29, 1943.

Bizerte, Tunisia:

This will be a short, short, short story for there’s little to tell except for flies, flies, flies. I can’t remember our tenting situation nor anything else – only sitting in an olive grove for shade and constantly brushing flies from our faces (dysentery also plagued the organization –ed). We sat on our barracks bags since there was nothing else to sit on. We, as always, had no idea of any plans for us, and were herded around like sheep. We remained in the olive grove for three days and these were the days of the invasion of Sicily (we learned later) which took place July 9, 1943 (operation “Husky” –ed). We landed in Palermo early August, following the initial landing and billeted in the bombed buildings of the Medical College (University of Palermo Polyclinic) and hospital there.

Our trip from Bizerte harbor (the planned staging area for movement to Sicily –ed), Tunisia was on board an LCI (Landing Craft Infantry). It took place at night on a rough sea. My lot in sleeping accommodations was the top bunk in a stack of five and in order to get into it I had to somehow hook my foot over the frame at one end, grab the frame at the other, and wedge my reclined body between the so-called mattress and ceiling. The boat must have been of very shallow draft (it looked like an elongated packing box) for the whole night long it slapped the water as we traveled. We reached Palermo, Sicily, August 6, 1943, some time in the afternoon and I was not seasick but so dizzy I could hardly stand or walk from the docks.

Palermo, Sicily:

The Nurses left the docks and were put into a large room with mattresses on the floor in another evacuation hospital that had come in ahead of us and were set up and operating (the 91st Evacuation Hospital –ed). I don’t remember what buildings they had but we were, in a day or so, moved close by in the bombed-out former medical college. They must have been nice buildings but were now badly damaged. For instance, the Nurses were set up into a building that had all the glass in the windows shattered and only black tarpaper to replace it. We were fortunate for we did have electricity, a bathroom, and eventually a small amount of warmth in the radiators. We slept on army cots with our sleeping bags for bedding. There were five of us in my room.

Following Seventh United States Army’s advance into Palermo, the port facilities could now be made available for use by medical units as a staging area for evacuation by sea. Patients were then evacuated from Palermo to Oran, Algeria or to Bizerte, Tunisia.

The hospital was later established in another building in the same area. I was assigned to the Orthopedic Section and the Officers’ ward—probably four rooms in all. Sicily was quite rapidly overcome by the Allies and after the landing at Salerno (operation “Avalanche”, amphibious landing September 9, 1943 –ed), Italy, took place, Naples was captured (October 1, 1943 –ed), and our troops became stalled on the Anzio Beachhead (operation “Shingle”, amphibious assault January 22, 1944 –ed). Through that whole period we stayed in Palermo, Sicily.

Helen I. Hyatt, during the unit’s second stay at Epinal, France. Picture taken in January 1945.

The city was typically Italian with spots of great beauty and horrible slums made worse by the bombing of the waterfront and areas near it. It was located at the foot of some fairly high and steep mountains. Some mornings we’d awaken to find the tops covered with snow.

Since there were other Army and Navy units stationed in Palermo, there was a good deal of social life in the evening mostly at the Officers’ clubs. We could date every night if we wished (we were still acting more as a holding hospital than an evacuation unit) and night life was pretty active. It was here that I met Bud who later became my husband (Captain Merwin J. DeKorp, CO, 46th QM Graves Registration Company, Seventh United States Army, which built the Epinal American Cemetery & Memorial in October 1944; the unit also participated in operation “Dragoon”).

Naples-Anzio-Salerno, Italy:

We reached Naples from Palermo by end of May 1944, this time on an LST (Landing Ship Tank) which was absolutely palatial and posh compared to the previous LCI journey to Sicily. As I recall we were, within a week or 10 days, sent on to Anzio where the Allied forces had finally left after a long period of fighting, horror and death.

Once again I seem to remember a boat trip and I think unloading onto lighters that took us to the beach where we landed June 7, 1944. We took over a previous hospital site and once again acted more like a station hospital. This time we operated closely together with the 38th Evacuation Hospital. Our main activity consisted in preparing and evacuating casualties to the Naples-Caserta area, Italy. I was assigned to the Shock Ward where First Lieutenant Augustus Stola, MC, was the Officer in charge (coincidentally, after the war was over, he with his family and I with mine, moved into the same neighborhood in Merrick, L.I., NY in 1948 where we became friends as well as his patients).

The fighting in Italy had gone through Rome (liberated June 5, 1944 –ed) and above, so again we were marking time. Several Nurses and Officers took advantage of this “lull” to travel to Naples and Rome on three-day leaves. While there I was greeted by a GI from my hospital who had been sent to find us and drive us back to our unit in Anzio. We’d been put on alert yet another time.

Hospital equipment being unloaded into buildings ready for opening in Mutzig, France. Photograph taken December 1944.

Courtesy John Sateja

This time we traveled by train to Naples and then down to Salerno where we set up as a station hospital and were not busy. The whole area was a staging area just prior to the invasion of Southern France (operation “Dragoon” August 15, 1944 –ed) but, as always, we were never told what was ahead for us.

Southern France—Central France:

We were ordered to return to Naples (Paestum area –ed) on August 11, 1944, where personnel were brought to authorized strength and some Nurses came in as replacements. While the 59th Evac boarded an LST, the Nurses were put on a Hospital Ship (most probably the USAHS “Marigold” which also carried the 95th Evacuation Hospital –ed) and almost treated like prisoners. We were required to stay in our quarters, which for once were quite nice. We were allowed on deck only on one side of the ship and orders were quite firm (nasty) about this. We passed between Sardinia and Corsica but were allowed to look only at Sardinia from the deck and not Corsica since it was not on our side of the ship.

After an overnight trip, this was August 25, 1944, we were unloaded via rope ladders onto lighters (shallow barge type rafts) that took us to shore which turned out to be Saint-Tropez. We were kept waiting on the beach area for a few hours until transportation arrived to pick us up.

The fighting must have moved quite fast for our hospital was taken inland to the town of Carpentras and set up in a clover field 3 days later. Our greatest danger was from the honeybees that were present by the many thousands. They especially gave us trouble when we brushed our teeth, which had to be done outside our tents.

Aerial view of the 59th Evacuation Hospital’s complex at Grünstadt, Germany. Photograph taken in March 1945.

Courtesy John Sateja

We were very gratified by native farmers coming into our area with cartloads (horse and cart was the predominant means of transport at that time) of melons, grapes, and other fresh produce. As I recall we got little if any of it since our patients came first. Our stay would be short as troops advanced rapidly leaving the medical installations too far to the rear.

Rioz, France:

My only memory of this small French town was that following a very long journey of traveling in a truck convoy, our being housed in tents, with rain and cold and mud to our ankles. We could get from one tent to another only on long 2 x 12s laid down as walks. The hospital opened September 19, 1944.

I wore long Johns for warmth and Leota and I tented with Martha Morris and Liz Liss.

Epinal, France:

This was quite a large town, very badly damaged by the bombing, shelling, etc. We set up in old French military installations and it proved to be one of our best stopovers for I can’t remember windows bombed out and we must have had heat but apart from working in the Shock Ward (like our current emergency rooms of today) there is not much I can recall. The period was early October 1944 (movement and preparation of the hospital installation was completed October 5, 1944, while the unit stayed in Epinal until the end of November 1944 –ed).

Picture of Helen I. Hyatt in Heidenheim, Germany. Taken end April, early May 1945.

We could sometimes hear the booming of cannon fire and were receiving patients with terrible injuries and cared for an unusual number of casualties with head injuries resulting from shell-bursts in forested areas. They were called tree-bursts and were simply shells fired into the treetops and exploding above ground which became shrapnel and numerous wood splinters that sliced areas of the body away, as likely as not the top of the head causing the brain to be severely affected. We placed waste baskets under the injured soldiers’ heads as they lay on litters placed on sawhorses side by side in our shock ward. There were so many of these cases that a brain surgeon was assigned to us for some time. Amazingly many patients survived but I often wonder how these GIs turned out and if the VA Hospitals would still be caring for many of them following the end of the war. Due to the weather conditions, more soldiers were received suffering from trenchfoot, respiratory diseases and fevers. As this proved to be a very busy period, we received some assistance from other Nurses, temporarily attached to our unit.

Another incident that really affected me was a young and handsome 18-year-old soldier who was brought in with both legs cut off mid-thigh. He was cold, dirty, almost black from the soot from the coal-burning engine of the troop train that cut his legs off. He was on a train load of replacements coming fresh out of what was referred to as “repple-depples” (GI slang for replacement depots) in the usual “40 & 8” type cars. It was fall, they were cold, and the train stopped frequently, for what reason they never knew, and the soldiers would get off the train and heat water on bonfires. But this time the train started up without warning and they had to grab their belongings and run to catch up. This person missed the car steps and fell under the train. He was in shock but lucid, talking a streak, and unaware that his legs were gone. What a senseless tragedy.

We were in Epinal for quite some time (5 October 1944 until 30 November 1944 –ed).

Mutzig, France:

As from 5 December 1944, we were housed in old brick, chilly, gloomy barracks buildings but at least buildings – not tents. As usual there were several Nurses to a room. I can’t remember working there. But on 30 December we were informed to pack in a hurry, we were moving out and, of all things, back to Epinal (the Germans started a last desperate push, which we called the “Battle of the Bulge”, and many American troops had to pull back). By this time we were tired of the cold and uncertainty and moving and believe me this was a low spot – our first (and only) retreat.

First Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt, enjoying a leave in Cannes, French Riviera, May 1945.

Epinal, France:

Back in Epinal, I lived with Leota Summer and Helen Baker, a friendly, thoughtful gal from Canarsie, NY – a graduate of Kings County Hospital (I have remained friends and close to both). The hospital was set up and we worked there. I can only remember being in the Admission or Shock Ward again. We did enjoy a period of inactivity the first months of 1945.

St. Avold, France & Grünstadt, Germany:

St. Avold was reached March 16, 1945, but the hospital already moved to another site, reopening 2 days later. Unfortunately our stays here in tents were so brief that I cannot remember much of anything. Hospital sites were so similar in the type of area – grassy, no trees, and this is where I first saw the famed German Autobahn (highway) which ran by our tented area.

At one of our later locations in Germany, we learned that President F. D. Roosevelt had died (April 12, 1945 –ed) and there was general sadness I think. My personal feeling was uncertainty as to our future. He’d been President for so long I must have felt we couldn’t do without him. From here we also saw large flights of Allied bombers still plastering Germany (the 59th Evac Hosp would eventually set up at Tiefenthal, Crailsheim, and Schnaitheim, Germany –ed).

Heidenheim, Germany:

In May 1945, the war was drawing to a close but we moved on to this mountainous, pretty town. It didn’t seem very large and we set up for work in our tents in a grassy bowl at the edge of town, and worked at taking in the last casualties, including many more German soldiers – many of them in their early teens – and American. While there, the Germans surrendered. As usual there was a castle on a hill but it was falling apart.

Major Merwin J. DeKorp and First Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt. Picture taken in October 1945.

The Dachau Concentration camp was nearby and when overtaken by the Allies (Americans) we (the Nurses) were asked to volunteer to go in and care for the poor skeleton-looking souls inhabiting the place. Our CO, Colonel O. B. Bolibaugh was appointed camp surgeon May 10, 1945. Helen Baker volunteered as did Liz Liss, Ann Schliesmann, and 5 others. I don’t know how long they were there but the inmates (political prisoners of different nationalities –ed) were scattered to different hospitals, buildings, dispensaries, and surely must have required quite a lot of TLC before they got back to normal. Besides ill health, starvation, typhus was running rampant and basically that was what the nursing care was needed for (a special typhus ward was set up –ed).

There was a truck farm near our hospital and Leota Summer and I would walk over the meadow and buy radishes. I think that was all the lady who lived there would sell to us but any fresh food was greatly enjoyed and appreciated. We had lived throughout our time overseas on army rations and they did not include fresh meat and vegetables.

Heading Home:

Adolf Hitler died May 2, 1945. After the collapse on the Eastern front, Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945 ending the war and we were quickly scattered; those of us more senior in our number of years in the service (high pointers) were sent home to the Zone of Interior and the junior Nurses headed for the Pacific Theater where the war with Japan was still going on. Destined to be routed through the Panama Canal, they never did get that far because the A-bombs caused the Japanese to surrender before expected, so the Nurses, were rerouted to New York and home.

I was first sent to Ellwangen, Germany, then traveled by ambulance (they were almost used as bus transportation) to Reims, France, thence by air (C-47 cargo planes with bucket seats along the sides) via the Canary Islands, Spain, to Manchester, North Hampshire, for four or five days and then again by air to a field near Wichita, Kansas, and finally by train to Fort Collins, Colorado. I was honorably discharged at Winter General Hospital (designated US Army General Hospital by WDGO # 67, dated 14 Dec 42, 1771-bed capacity, first patient received 5 Jul 43 –ed) Topeka, Shawnee County, Kansas, November 17, 1945, having faithfully served Uncle Sam 3 years, 5 months, and 24 days.

Battles & Campaign Awards – First Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt

Sicily (GO # 75, WD 1943)

Rome-Arno (GO # 80, WD 1944)

Southern France (GO # 80, WD 1944)

Rhineland (GO # 33, WD 1945)

Central Europe (GO # 48, WD 1945)

Decorations & Medals – First Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt

European-African-Middle Eastern Service Medal

A happy family. From L to R: Bud, Helen, and daughter Jane. Picture taken December 1946.

Helen passed away at age 88 in June 2003, which was 30 years and 3 days after the death of her husband “Bud”.

We are particularly indebted to Jane Verderosa, daughter of First Lieutenant Helen I. Hyatt (N-742643) ANC Officer who served with the 59th Evacuation Hospital and Major Merwin J. DeKorp (O-406311) CO of the 46th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company. Without her kind help this Testimony would not have been written. Thank you so much for sharing the above precious WW2 recollections, documents and photos with the MRC Staff. We’re still looking for a complete personnel roster of subject hospital. We would also like to thank John Sateja, nephew of T/Sgt. Charles N. Sateja who also served with the 59th Evacuation Hospital in WW2, for kindly sharing with us a large number of illustrations relating to subject unit.