Veteran’s Testimony – Virginia C. Cooley American Red Cross Staff Aide / 188th General Hospital

Mrs. Virginia C. Cooley-Strong, ARC Staff Aide (ARC 41350). Picture taken in September 1945.

Introduction:

My name is Virginia Carolyn Cooley. I was born 10 July 1907 in Manchester, Ohio, United States of America. After joining the American Red Cross in 1944, I was assigned to a group of personnel detached for service overseas with a US Army Hospital unit.

Movement Overseas:

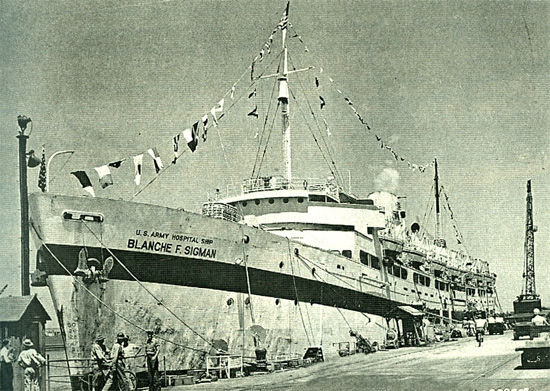

We arrived in London on September 8, 1944 via Liverpool on the Hospital Ship USAHS “Blanche F. Sigman”, a converted Liberty Ship (ex-“Stanford White”, taken over by the War Department and converted into a Hospital Ship consisting of 44 wards, 2 operating rooms, 2 dispensaries, 1 pharmacy, 1 dental clinic, and several dressing stations, with a total bed capacity of 490. On 29 May 1944, the vessel was formally re-named Blanche F. Sigman, 1st Lieutenant, ANC, Chief Nurse of the 95th Evacuation Hospital who was killed in action at Anzio Beachhead, Italy, 7 February 1944 –ed). We had waited three weeks in Charleston Port of Embarkation, South Carolina, for the ship. There were 19 American Red Cross personnel on board to be used in various United Kingdom Hospitals as replacements. It was the ship’s third voyage overseas.

“USAHS Blanche F. Sigman”, at Charleston, South Carolina, being restocked and refueled for another trip overseas.

Assignment:

The “D-Day” Invasion of France (6 June 1944) was successfully completed and U.S. troops were now rolling across France heading east to the enemy’s Fatherland, but with fearful casualties – the war in Europe had eight more months to go, and our final destination, the 188th General Hospital in Cirencester, old Roman town in the Cotswolds, was one of 98 or so medical units spread out from the English Channel to the Scottish border. The General Hospital to which I had been assigned, was a Communications Zone (ComZ) type usually housed under tentage or in improvised huts or barracks, and stationed in a Theater of Operations (overseas). Its task was to perform fourth echelon medical service receiving patients from Evacuation Hospitals of the combat zone by ambulance or hospital train, motor ambulance, or by airplane. American Red Cross personnel, i.e. civilians, were usually attached to carry out welfare work among the patients, arrange for shows and recreation, provide personal services, etc. I belonged to the “Hospital Service” group (not the “Club Service”) which consisted of social service and recreational programs for patients treated in Military Hospitals. Resident A.R.C. detachments were assigned to a specific organization and consisted of social workers, recreation workers, a secretary, and additional workers and volunteers as needed and as available.

The Hospital had been in operation four months only, but by next May it would have its 10,000th patient – its capacity was normally 1500 beds. Even so, deaths were few and far between. Until late spring of 1945 not more than half a dozen had occurred. In a way it was a recuperative hospital – when a man was able to be flown from the war zone, yet needed considerable surgery and care, say 60 days of it, he would be transferred to the United Kingdom to be rehabilitated for limited service, or returned home to the Zone of Interior if long treatment was necessary.

Top: Patients relaxing in the Receiving Hall, 188th General Hospital, Cirencester, England.

Bottom: “Symphony Hour”, provided by the (British) Entertainments National Service Association for the 188th General Hospital’s patients. ENSA was set up in 1939 to provide entertainment to H.M. Armed Forces personnel during WW2; later extended to Allied Forces stationed in the British Isles.

United Kingdom:

An Assistant Field Director, her Secretary, and three recreation workers comprised the average A.R.C. Detachment staff.

“The Girls from Nissen Hut No. 110”- 188th General Hospital. Back row, L to R: Sophie E. Shramko (ARC Asst. Field Director), Doris D. Duston (ARC Staff Aide). Front row, L to R: Phyllis A. Coe (ARC Secretary), Rachel E. Garrett (ARC Staff Aide), Virginia C. Cooley (ARC Staff Aide).

I was at the bottom, a lowly Staff Aide, just where I belonged. I had no musical ability, no recreation experience, and no social work in my background. I was an English major in college, later a dress sales woman, an office clerk, an interviewer, and a publicist for the U.S. Employment Service. Also, I had worked a year on the Federal Writers Project, helping to compile the “Ohio Guide”. I had written some historical articles for a trade publication, and done some freelance newspaper work on the side. My only qualification for “work with sick soldiers” (as one of the Washington staff called it) was an adventurous spirit and a compelling desire to be of direct, tangible service to wounded patients far from home and family. It was selfish enough and no credit is expected. We worked harder than ever before or since in our lives, and enjoyed it more.

GIs of the 188th General Hospital on a day trip to Gloucester Cathedral. Picture taken in November 1944.

We were forever admiring the Nurses and Medical Officers with whom we shared an equal military status socially, and “in case of capture”. But we never were allowed to give a patient medical aid, not even a glass of water. Ours was personal service and diversion, and I think we succeeded except that we were spread too thin. Hospital experience, as a patient, is one that is most easily forgotten and should be, but I hope some of the 10,000 remember the American Red Cross gals with a friendly feeling, even if they have forgotten us individually. Seldom did they write back from home, nor did we expect it. We just wanted them to be happy and successful. We weren’t allowed to date G.I.s, hence the endless cups of Mess Hall coffee.

Nevertheless, we were invited to adapt to the English weather, the black-outs, the air raids, the alerts, the rationing, the hard and uncomfortable cots, and the English stoves. Sometimes it became difficult and at times, there were periods of loneliness. We couldn’t just keep on organizing birthday parties, teach the patients some arts and crafts, have dinner at the Allied Officers’ Club, meet representatives and members of the Red Cross, visit with English friends, go to a dance, attend shows or parties, visit nearby places of interest. Life in a Nissen hut could be most congenial, but living the life of a ‘goldfish’ has its drawbacks. Working days were long, as we had to get up at 0630 every morning.

Officers’ Staff – 188th General Hospital

Colonel I. A. Abrahamson – Commanding Officer

Lt. Colonel M. C. Davenport – Executive Officer

2d Lieutenant J. A. Juchem, Sr. – Adjutant

1st Lieutenant E. A. Haugum – Principal Chief Nurse

2d Lieutenant A. L. Bechtelheimer – Assistant Chief Nurse

By October the twilight began at 1600 hours and soon it was dark, and much colder by November than it had ever been. Our Nissen hut (no. 110) had six beds, one a spare for guests. Its heart was an old iron stove that never wanted to burn, especially coke. It usually went completely out at night so we took turns getting up to start it, after which we made tea, coffee, and toast, and served our mates in bed. This way we got an hour’s extra sleep and missed the powdered eggs at the mess.

Winter scene view taken from Nissen Hut No. 110, Christmas Eve 1944, 188th General Hospital, Cirencester, England.

Once somebody made a fire on one match, but it was agreed that to be a champ you had to do it with the only match in the hut.

My most remembered Christmas was 1944 at the 188th General Hospital – our 1500-bed unit was overflowing then with casualties from the Battle of the Bulge, and patient census ran high. Many Nissen hut wards were extended into extra tents. It was bitter cold all over Northern Europe – we were told to save on coal. Our complex of huts lay on a snow covered Cotswolds “estate”. Dusk would close in by 1600, and later we would crunch along in the black-out to our own huts and comforting tea kettles. After supper, we were off again to the wards, with supplies, books, entertainers, movies. It was like a compact village, shut off in a silent, wintery world. As long as the flow of supplies continued, we were able to provide our patients, whom we nicknamed the “red bathrobes”, with the necessary ‘goodies’, such as playing cards, newspapers, magazines, books, stationery, checkers, and more.

I had been appointed to see that all 44 wards had Christmas decorations for the beautiful trees presented us by the town of Cirencester. There were no ornaments for sale, but our Red Cross shelves had colored construction paper, felt and yarn. The Mess Sergeant sent over all his tin cans, and we set the ambulatory patients to work cutting tin stars and spirals. Plexiglass shavings became snow. We divided the other materials between willing bed patients, it is called occupational therapy. The men set to work and produced bushels of paper chains and cornucopias. A few “artists” created lovely things with silver and cellophane candy, gum, and cigarette wrappers. All the decorations were divided fairly, because there was a contest on for the best decorated ward.

During Christmas week groups of evacuated British children were brought by their teachers to sing carols for the patients. This was very affecting as some men were missing their own children, but all had saved their candy rations so the small guests were repaid. We gave an afternoon party for the town children, expecting 200, but 300 came! There was a rush for more cookies and hot cocoa, and hastily wrapped presents. These consisted mostly of books and some of the children waited at the end to “exchange” their gifts – they had read the books already.

By Christmas Eve the fog and mist had crystallized into a thick hoar frost, turning the earth into a fairyland. The bare shrubs, trees, and wires glittered like rhinestones. A full moon shone mistily on the sparkling white world. Christmas morning dawned pink and clear. After breakfast a committee of Medical Officers set off with notebooks to judge the decorations. It was an amazing experience – some wards were festooned with green ivy, some with paper streamers, and some had funny cartoons and life-sized characters. The Christmas trees were gay and lovely.

An orthopedic ward with many traction patients took first prize. Someone had located show-card paint, and one of the patients, with a Nurse’s help, had created “stained glass windows” with Nativity scenes. Paper painted like bricks covered their brown bookcase, making it a mantel where GI socks were hung. Red paper and flashlights made a cosy glow in the “fireplace” below. The homely scene, with the men lying quietly in bed, was almost too much for the judges and at least one American Red Cross girl – had to choke back tears. It was sad about the packages from home, the parcels were following the men and wouldn’t arrive for weeks, but they were always shared.

Right at noon on Christmas Day a sort of miracle happened. The long-awaited PA system was at last in order, and suddenly the sound of music wafted out through every building bringing the Armed Forces Radio program – it was pure joy!

Wedding Bells:

A member of the 5th Armored Division (C Company, 15th Armored Infantry Battalion), who had been badly wounded on patrol in the Huertgen Forest (the fighting to capture the Hürtgen Forest area stretched from September into December 1944 when the German counteroffensive in the Belgian Ardennes disrupted the entire Allied front – during these months, the battles of the V and VII Corps, First United States Army became one of the most costly and controversial American operations of the war in the E.T.O. – eventually, the 1st, 4th, 8th, 9th, and 28th Infantry Divisions, 2d Ranger Battalion, 46th Armored Infantry Battalion and Combat Command R, 5th Armored Division, were all heavily engaged in the fighting – altogether US forces suffered over 30,000 casualties in killed, wounded, missing in action, combat exhaustion, and to various diseases and non-battle injuries –ed) arrived at the 188th that very day. He complained that it was “so Christmas-y” he couldn’t sleep! But I made it up to him the next Christmas, because we were married that spring, in England. A.R.C. Staff Aide Virginia C. Cooley (ARC 41350) and Private Jack C. Strong (ASN 38059844) were married in May 1945.

29 May 1945, wedding at St. Gabriel’s Church, Hanley Swan Parish, Worcestershire, England. Bride, Virginia C. Cooley, and groom, Jack C. Strong are far right.

Postwar period:

In fall of 1945, Virginia left the United Kingdom, sailing back home on the liner “Queen Elizabeth”, turned temporarily into a troopship for returning GIs. It should not be forgotten that ARC workers made sacrifices too, leaving their homes to serve members of the US Armed Forces in foreign lands, often in difficult situations, but with dedication and pride. She and her husband, Pfc Jack C. Strong, a former patient at the 188th, went to live in California, and a year later Virginia gave birth to a daughter, Stephanie.

In 1952 she returned to her home state Ohio and worked for two years as a member of the civilian personnel at Wright Patterson AFB in Dayton.

In 1954, she left the continental United States, went to Germany and worked as a civilian at the US Army’s European Headquarters (USAREUR) in Heidelberg.

Virginia C. Cooley retired in 1972 from Hill AFB in Ogden, Utah, where she had worked for several years as Assistant Editor of the Base newspaper, “The Hill Top Times”.

Photo taken during Lt. General Ben Lear’s inspection tour of the 826th Convalescent Center at Coventry, England, 2 May 1945. From L to R: Dave Roberts (US War Correspondent), Virginia C. Cooley (ARC Staff Aide), Lt. General Benjamin Lear (Deputy CG ETOUSA), unknown, Maj. General Paul R. Hawley (Chief Surgeon ETOUSA), unknown (another US War Correspondent).

We are truly indebted to Stephanie Strong, daughter of American Red Cross Staff Aide, Virginia Cooley (ARC 41350), a member of the ARC Detachment serving with the 188th General Hospital in the United Kingdom, for providing us with excerpts of her Mother’s Diary and pictures. Our sincere thanks for her kind contribution. Readers who want to learn more about Miss Virginia Cooley’s WW2 service are invited to consult the following webpages: www.abroadinaquandary.blogspot.com/